Henry Deringer’s

Pocket Pistol

And the cartridge versions born from the concept

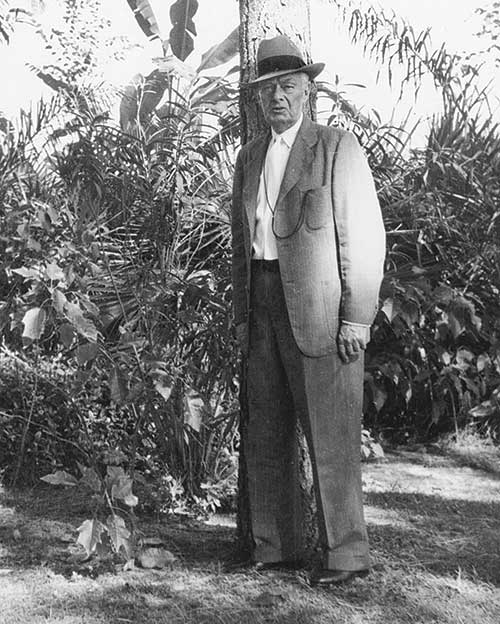

My great uncle, the late Lester Williams, was a Southern shooting gentleman. When he wasn’t managing his orange grove at Turkey Lake, just outside of Orlando, Fla., you would find him bass fishing or raccoon hunting with a nondescript mutt or simply fiddling around with his modest gun collection. Living remotely, he was a cautious man. His home was wired so he could turn on every light in the house while keeping the oversized master bedroom dark.

On one side of his bed’s headboard was slung a target-sighted, Colt Bisley in .45 Colt. On the other side hung an early Colt Model 1911 military model with “United States Property” marks and rumored to have been liberated from the Capone gang. What is burned in my memory is on his trips to town, he always packed two .41-caliber Remington derringers in oversize watch pockets he had sewn especially into all his better trousers.

Hard Cocking

Derringer packing simply ran in the family. His wife carried a Colt Third Model derringer in .41 rimfire in her purse and her sister, my Texan grandmother, carried the mate to that gun in her purse as well. This was in the 1950’s, you understand, not the 1850’s. Why did the women of the family pack Colt Third Models? Well, a woman can easily cock a Colt, but a woman, child and few men can cock an original Remington Double Derringer using just the thumb of the shooting hand alone. I’m sure a few unpracticed ladies and gents were sped on their way to heaven just trying to get off their first, desperate shot with a Remington Double Derringer.

The secret is to catch the hammer spur of the Remington in the web of your hand between the thumb and forefinger, roll the derringer forward, cocking the hammer as your hand moves down to firmly take hold of the grip.

Trickling down the family tree, those two Remingtons and two Colts plus a shoebox full of vintage .41 rimfire ammunition finally arrived at my doorstep. It was a magical moment, and it was time to study up on derringers.

Born in 1786 in Easton, Pa., Henry Deringer, Jr. (note his proper name has only one “r”) was the son of a German gunsmith, and following a normal apprenticeship in his father’s shop, he set up his own gunmaking business in Philadelphia in 1806. He didn’t start off making deringers; rather it was the production of rifles, muskets and pistols for the commercial and government trades. Over time he became increasingly known for the quality of his pistols, and they became his focus. It is thought the arm we think of when the term “derringer” is used didn’t evolve until about 1849 when Deringer was well into his 60’s.

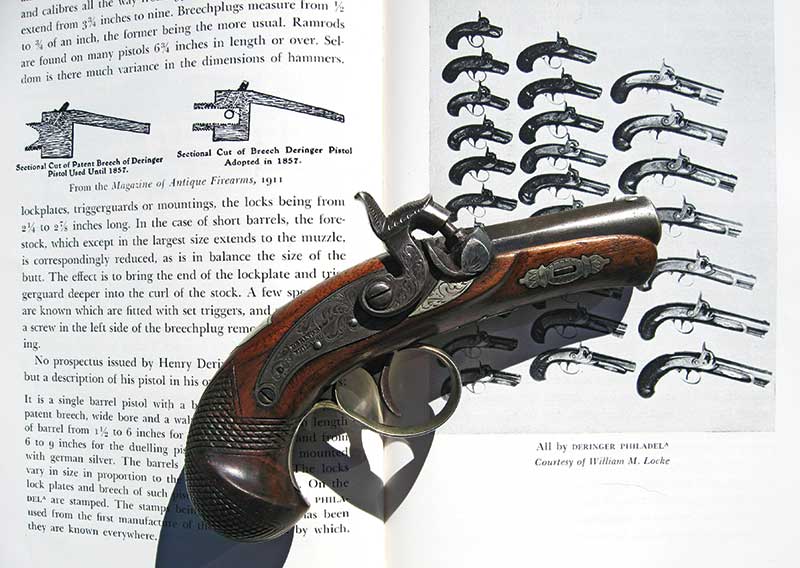

Pictured here, courtesy of the Frontier Gun Shop in Tucson, Ariz., is a classic example of Deringer’s percussion pocket pistol: A black walnut stock with a checkered bird’s head grip, foliate engraved German silver mountings, a petite back-action lock with a generous hammer spur, a short .41-caliber rifled barrel with a patent breech and with unique contour beginning as an octagon and ending with the sides and bottom of the barrel becoming rounded at the muzzle.

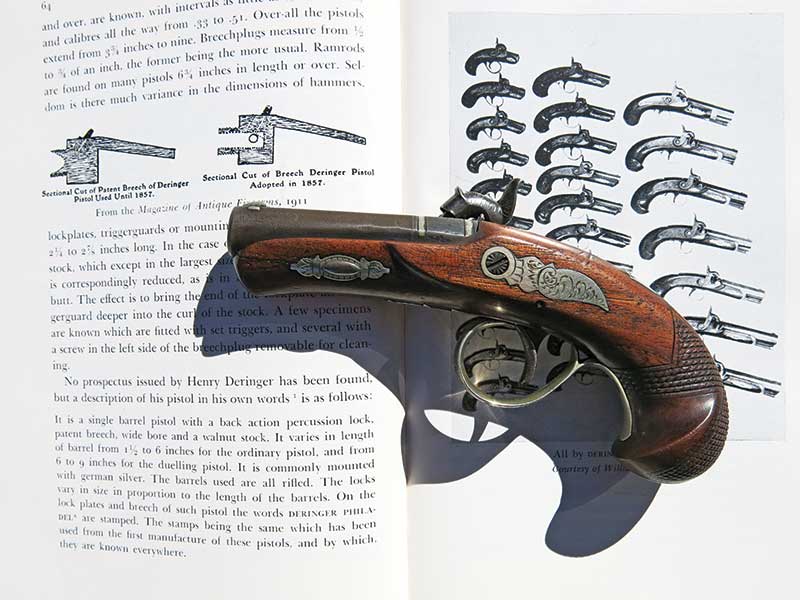

Not all of Derringer’s deringers fit this classic form. In his book, Henry Deringer’s Pocket Pistol, author, John Parsons, observes, “Barrel lengths from 27/32 of an inch, measured exclusive of the breechplug, to 4 inches and over, are known… and calibers all the way from .33 to .51. Overall the pistols extend from 3-3/4 inches to 9 inches.

“The lockplate and top of the breechplug each bear the trademark ‘DERINGER PHILADEL in two lines (with a small capital A above and to the right of the last L). In 1866, Deringer testified that in the previous 10 years he had sold 5,280 pairs of pistols at an average profit of $7 a pair.”

Deringer’s derringers were widely imitated by competitors and readily faked. The spelling of the name “Deringer” was quickly corrupted to “Derringer” with two r’s to avoid trademark infringements.

By the end of the Civil War, the days of Deringer’s percussion deringer were over. The new .41 Short rimfire cartridge had been introduced in a breech-loading derringer by the National Arms Company in 1863, but Deringer’s fame was intact. His name by that time had become a household and generic word applied to any petite pocket pistol.

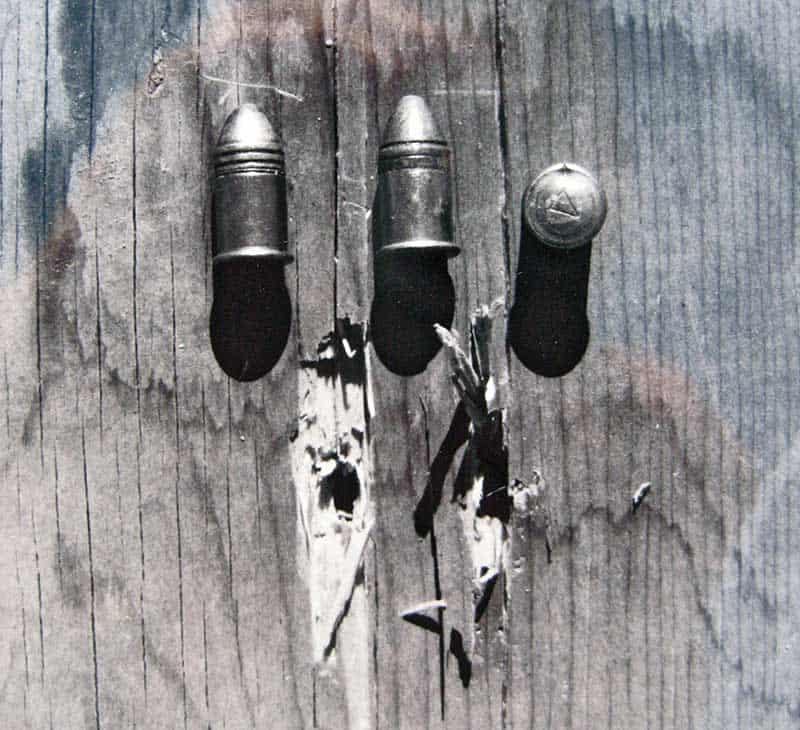

And what about the .41 Short rimfire cartridge? Frank Barnes’ invaluable reference, Cartridges of the World, has this to say about it: “The .41 Rimfire Short is so underpowered as to be worthless for anything but rats, mice or sparrows at short range. Fired from the average derringer at a tree or hard object 15 to 25 yards away, the bullet will often bounce back and land at your feet.”

With a shoebox full of vintage .41 Shorts and four derringers, I was to find otherwise.

In that shoebox were the old familiar green Remington boxes marked “Kleanbore,” blue Peters boxes marked “Rustless,” green Winchester boxes marked “Stainless” and the cream of the crop, blue and yellow Western boxes marked “Lubaloy.” In addition to this storehouse of old .41 rimfire, I ordered some new, Brazilian-made, .41 rimfire Navy Arms had commissioned.

The standard load was a soft lead 130-grain, heeled bullet over a pinch of smokeless powder in a short, copper case. Aside from the modern Navy Arms ammunition, the Western “Lubaloy” coated ammunition was outstanding. The Western bullets were given a golden wash of “Lubaloy” copper so the whole round just gleamed like polished copper. Western also coated their ammunition with a Vaseline-like lubricant that apparently helped to preserve the potency of their .41 Shorts.

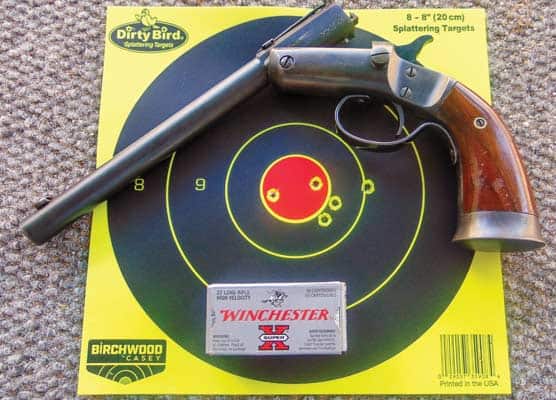

Still, with some trepidation, I loaded up one of the Remington Double Derringers with two rounds of Western .41 Shorts, moved back 15 feet and let fly at a dead, but rock-hard, mesquite tree in the back yard. Fully expecting the bullets to come bouncing back, I was stunned when both bullets were driven out of sight into the tough mesquite trunk. I was also surprised how little recoil the derringer produced. It was time to wheel out my PACT Professional Chronograph and see exactly what ballistics the .41 Short rimfire was delivering.

From the 3-inch barrels of a Remington, the Western Lubaloys averaged 532 fps and the new lot of Navy Arms ammunition, 621 fps. A 130-grain bullet at 621 fps churns up 111 ft-lbs of energy. As a comparison, the current .38 S&W load with a 145-grain bullet and a muzzle velocity of 685 fps from a 4-inch barrel delivers 151 ft-lbs of energy, and with my chronograph screens set 10 feet from the muzzle of the derringer, I was seriously understating the actual muzzle velocity of the .41 Shorts. The .41 rimfire is not a puny round.

After the mesquite tree incident, I was curious about the penetration of the .41 Short, so I soaked some old phone directories in water and backed them up with a 3/4-inch pine board. I was expecting to recover the .41-caliber bullets somewhere inside the directories, but at 10 feet, the Lubaloy and the Navy Arms rounds simply sailed through all 5 inches of the water soaked directories, punched through that 3/4-inch piece of pine and kept on going.

An “underpowered and worthless round”? I don’t think so. Delivering a .41-caliber hole from a sneak pistol, it was an effective cartridge, and that’s why Colt produced and sold 63,500 First, Second and Third Model derringers from 1870 to 1912 and Remington, 150,000 of their over/under barreled model which was in production from 1866 right up to 1935!

Today, Henry’s little pocket pistols are still very much part of the personal-defense scene. His name may have been corrupted to “Derringer,” but with contemporary models being produced by Bond Arms, his vision is very much alive.

Henry Deringer’s Pocket Pistol

by John E. Parsons,

Hardcover, 255 pages,

© 1952, Out-of-Print.

GUNS Carry Options

Get More Carry Options content!

Sign up for the newsletter here: