Flash Bang Follies

A Primer On Distraction Devices

“Snick … tinkle … BOOOOOM!!!!”

If you’re sitting there on the floor, temporarily deaf and partially blinded, you probably just met one of my favorite friends — he’s loud and dangerous, and beloved by police and military folks. He’s the “Distraction Device,” aka “stun grenade,” aka “flash bang.”

I’ve used countless distraction devices in training and actual SWAT operations, but I don’t give them much thought anymore. But, back when, I always enjoyed sensations involved: the growing anxiety as you straighten the pin standing alongside a door, the anticipation as you throw, the flashbulb-from-Hell burst, and then the rush of adrenaline when the thumping concussion hits your chest like a baseball bat. Much like Robert Duvall in Apocalypse Now, I truly loved the smell of magnesium flash powder in the morning!

Those days are a couple of decades behind me, at least until recently. A few days ago, we were having a discussion here at GUNS about a non-lethal electronic distraction device I had received from a manufacturer. After explaining what I knew about the devices and my experiences of “banging” people, one of our staffers said, “There’s your online story for this week.” Well, heck, I guess Ashley was right, so here we go!

Flash Bang Defined

Distraction devices first came into the public consciousness on May 5, 1980, when the British SAS stormed the Iranian Embassy in London. The six gunmen took 26 hostages and held them for six days until the Brits had decided they’d had enough after the bad guys killed a hostage to prove they were serious. Finally, as live television looked on, SAS troopers rappelled down the front of the building, set off explosive frame charges on the windows, and tossed explosive distraction devices inside. In the end, one hostage was killed, while two others were wounded. The SAS killed all the bad guys except one, and no troupers suffered serious injury. The operation was considered a success, and the world was now intrigued by explosives used in such a fashion.

Forward into the nineties. By this time, distraction devices had become a standard part of civilian law enforcement, especially SWAT teams who used them in cases of “dynamic entry,” a rapid assault on a building where a hostage-taker or gunman might be waiting. The military eventually jumped on the bandwagon, even though individual units had been experimenting since the SAS incident.

The idea of a distraction device is simple: if someone is waiting to shoot a soldier or cop coming through the door, it’s much more difficult when you are blinded by a brilliant flash, almost deaf from an exceptionally loud noise, and physically thumped by the accompanying overpressure. Speaking from experience, being on the receiving end of a flash-bang is like taking a hard smack to the face — you can fight through it, but it certainly puts a major damper on your enthusiasm.

Most distraction devices aren’t explosives, even though they are considered “destructive devices” for possession, shipping and storage purposes. This means you can own and possess them, but you’d better have the necessary permits and a darn good reason. There are “civilian” distraction devices available, but they are essentially firecrackers made to look like a grenade. Personally, I’d save your money for something more useful, like ammunition.

Bangin’ 101

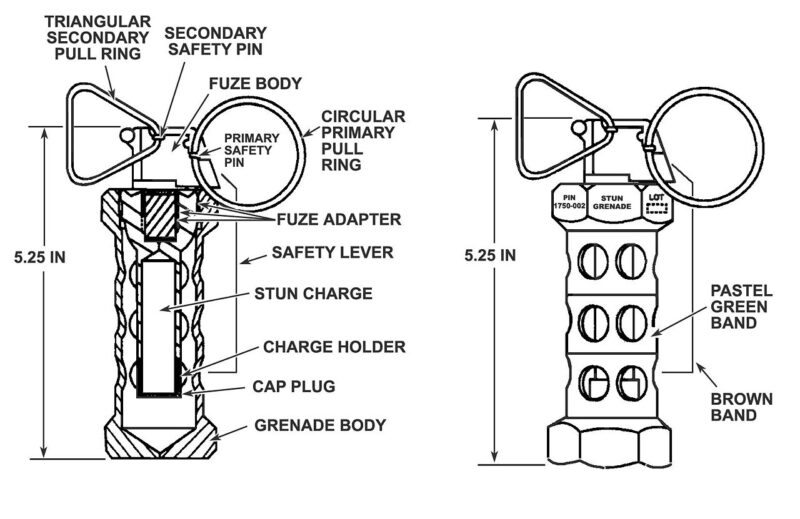

A distraction device is essentially a turbo-charged firecracker made with flash powder, detonated by a time-delay spoon arrangement with pull-pin safety, exactly like a military fragmentation hand grenade. There is flame and overpressure, but the energetic material inside is actually burning rather than exploding, albeit with blinding speed and ferocity. The outer casing is either cardboard or blast-proof heavy steel to keep any deadly fragmentation to a minimum.

Distraction devices are categorized as “less lethal” munitions. Notice I didn’t say “non-lethal” as is often mistakenly reported — flash bang devices have killed or maimed an estimated 50 people in the U.S. in the last 20 years. Thus, when authorizing the use of a stun grenade, commanders and officers must consider the possible risk/reward of collateral damage. For example, a person refusing to cooperate while being arrested for parking violations inside their preschool classroom probably won’t justify officers using “a bang,” while a barricaded hostage-taker is certainly deserving of all you can throw, plus one.

While pressure and burn injuries at close range are possible, the biggest risk with distraction devices is fire. The Iranian Embassy went up in smoke when the SAS devices set the curtains on fire. My former team nearly burned a house down when a distraction device took a bad bounce and landed between couch cushions. The criminals were in handcuffs in the bedroom when somebody suddenly realized the living room couch was on fire and quickly spreading. This is one reason you’ll always see a fire engine nearby at SWAT incidents.

Once upon a time, I also nearly killed my entire team during training. We had reached a barricade stalemate inside an abandoned warehouse with a role-playing hostage taker when I pulled the pin on my banger. Several people quickly pointed out, screaming through their gas masks, that the atmosphere was heavy with OC gas and I need to immediately stop. In my desire to rush the bad guy, I had forgotten that both OC and its carrier solvent, isopropyl alcohol, make for a dandy flash fire if there is an ignition source. Oops. This is one reason you retain the safety pin from the device on your finger, unlike the movies where they toss it away before chucking their hand grenade.

And, by the way, if you ever try to pull the pin with your teeth like in the action flicks, you’ll be visiting a dental surgeon immediately afterward. The safety on most grenades and similar devices is a cotter pin with a steel ring for gripping with your finger (we always used the ring finger). Step one of deployment is to straighten the legs of the cotter pin beforehand because if you leave the legs bent, you’re liable to rip your finger off before the pin will pull free! You can imagine what it’d do to your bridge work.

Fire in the Hole!

Once you toss the distraction device, you have — typically — 1.5 seconds before the delay fuse sets off the flash powder. This is longer than the typical military grenade delay of 3-4 seconds because of shorter deployment distances involved, plus you don’t want to give the bad guy time to throw the device back at you. With the short delay, we found our target would instinctively look at the source of the strange metallic sound in their immediate proximity, and by the time the flash bang did its thing, they were usually staring right at it. This proved less-than-optimal for the target.

Most pyrotechnic distraction devices put out several million candela for a few milliseconds and noise of around 160-170 decibels — this is louder than a jet engine at close range, or even a Mitch Ryder and the Detroit Wheels concert! The overpressure in a small space is also remarkable.

Though I believe this use is contraindicated by policy, I’ll just point out that you don’t ever want to be inside a passenger vehicle when a distraction device is thrown through the side window. The nice thing for the cops is that you can then visually search everywhere in the vehicle because all the doors, hood and trunk will fly open in a supplicant gesture of surrender.

You’re also not supposed to throw them into a pond when people are trespassing and refusing to exit the water. However, the resulting “thump” will cause most folks to sprint right into the paddy wagon. It’ll also give you a nice sample of the local fish population, which you can count as they float belly-up on the surface. At least, this is what I’ve heard on the street …

Sometimes, distraction devices also include small rubber balls. In addition to the noise, flash and pressure of a distraction device, these “stingball” grenades pack the extra fun of hard-rubber balls pelting you at sufficient velocity to sting like the dickens. We never found them necessary, though riot squads often use them to cool the ardor of looters.

Backlash

Some agencies are starting to rein in the use of distraction devices because of liability. There have been tragic cases where thrown devices had landed in baby cribs and other such no-no areas, but overall, they are still the best available technology for distracting dangerous individuals prior to attempted capture. It’s sad that good tools are being taken away because of rare individual mistakes or simply bad luck.

This a major reason for the current focus on developing even safer payloads such as electronic noisemakers or popping balloons. The latter uses a small-but-stout rubber bladder, which is inflated with high-pressure CO2. When it eventually bursts, it is said to produce a substantial noise and noticeable overpressure, though nothing like a real pyrotechnic device. It can also have OC dust added to disperse when the bladder explodes. Electronic distraction devices, meanwhile, rely on bright LED lights and sirens.

Instead, give me a good, old-fashioned “banger” any day. Sure, they sometimes kill people and burn down houses, but in the grand scheme of things, they are a mature technology that is practical and proven effective. While the occasional tragedy is indeed sad — and we should always work and train to minimize such collateral danger — there is a greater good for all by keeping these remarkable devices in the arsenal of the police and military.

And you can’t begin to imagine what they can do to a terrorist groundhog hole. At least, this is what I’ve heard on the street …

Want more online exclusives from GUNS Magazine delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for our FREE weekly email newsletters.