A Veterans Day Remembrance

Honoring Unlikely Heroes

One was called “The man who won the war for us” by Supreme Allied Commander Dwight Eisenhower, though he never served in uniform during that war. The other was an enlisted soldier, the quintessential “private from Palookaville.” His face was almost unknown to the troops, but he created the two best-known faces in the European Theater of Operations. Both men are all but forgotten now. Let’s change that this Veterans Day.

On Veterans Day, November 11th, it is only fitting that we honor the bravery of our most valiant warriors, living and dead, and the sacrifices of our own loved ones who served — and those still serving — in uniform. But along with them, I offer the memories of these two men.

A few years before America entered World War II, the net assets of a certain barrel-chested Louisiana boat builder amounted to $13,639, and he didn’t have a single contract with the US Navy. In late 1943, the Navy listed over 14,000 vessels in its inventory. Ninety-two percent of them, some 12,964 units, were designed by that fierce, stout bayou boatman, and most were built at his own assembly yard. Officially labeled “LCVPs” and “LCMs” for Landing Craft, Vehicle (and) Personnel, and Landing Craft, Mechanized, those designations were seldom spoken. In all their variants, they were simply known as “Higgins boats,” and they were the single development of the war that profoundly shaped the winning Allied strategy.

Andrew Jackson Higgins was born in Nebraska in 1886. One of 10 siblings, he grew up fast, tough and enterprising. As a kid, he organized newspaper delivery and gardening services, hiring older boys for labor and then selling the businesses to adults. As a teenager, Higgins worked summers in Wyoming logging camps. In winter, he designed and built iceboats, racing them on frozen lakes, and as a volunteer militiaman, he observed amphibious operations on the Platte River. He developed lifelong interests in military strategy, boat design, forestry and the lumber industry.

He moved to Louisiana, where he designed shallow-draft spoonbill-prowed boats to run lumber and equipment on waterways denied to less agile designs. To avoid damage from floating or submerged obstacles, he placed his boats’ propellers in U-shaped tunnels in their hulls.

The Boat

The storm clouds of World War II brought all four of his passions together. The final element of his design was a hinged landing ramp in the bow. Now his boats — and no others — could be run full-throttle up onto beaches, drop their ramps to disgorge men, tanks and tons of equipment, then simply reverse off the beach, turn in their own length, and scoot back to mother ships offshore.

Previously, military forces could not land significant men and supplies except by seizing an existing port to offload onto solid quays. In 1942, British forces tried that at Dieppe, France. They were slaughtered, and a successful invasion of Fortress Europe looked impossible. But with Higgins boats, every beach in the world became open to Allied invasion.

There’s far more to the Higgins story, and I urge you to find and read it. His personal energy, his brilliant manufacturing practices, and his selfless release of his patents, royalty-free, to help win the war, though it later impoverished him, are nothing less than inspiring. I’ll end with this: Hitler personally and bitterly cursed Andrew Higgins but grudgingly admitted to his staff, “Truly, this man is the new Noah.”

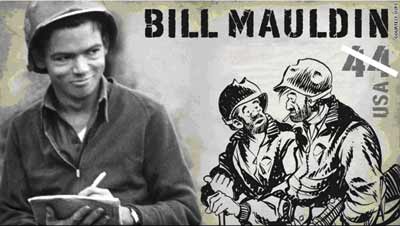

William Henry “Bill” Mauldin was born in Mountain Park, New Mexico, in 1921. His dad had served as an artilleryman in World War I, and his grandfather was a cavalry scout during the Apache Wars. A shy, skinny kid, he loved doodling cartoons and continued doing that as a 19-year-old private in the National Guard. He was federalized into the Army in 1940 and volunteered to draw cartoons for the 45th Division News. Bill had just turned 20 years old when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor.

Three years later, at 23, he had won the first of two Pulitzer Prizes, one of his cartoons made the cover of Time Magazine, and the first book of his work, Up Front, was a best-seller. Every combat infantryman in Europe knew who he was. But he was still a shy, skinny kid with some pencils and a paper tablet — and still an enlisted dogface soldier.

Mauldin’s division made the invasion of Sicily and then of the boot of Italy, fighting their way up the Apennine Mountains to the Alps, a grueling, deadly campaign. His doodles rapidly became the most popular feature of the paper and began appearing in the military-wide Stars and Stripes.

Always at the front, as the war shaped the American infantryman, the infantryman shaped Bill’s cartoons. He was one of them; one of the anonymous, long-suffering ex-blue collar workers called to duty and cast into the murderous maelstrom of modern warfare, occupying the lowest, most dangerous rung of the military ladder. He ran the same risks, and when he was wounded near Monte Cassino, their bond with Bill was sealed. With an open heart and a compassionate eye, he saw them and their war as they saw it. In return, the troops embraced Bill and the two iconic infantrymen he invented to represent them: Willie and Joe, American soldiers, unlettered, unsophisticated, undaunted and undefeated.

It would be difficult, perhaps even impossible, to express in words how Bill’s cartoons touched those infantrymen. They weren’t cute or funny in any conventional sense. As Bill explained it, “Humor is really laughing off a hurt, grinning at misery.” The trigger-pullers knew he cartooned for them, not for the folks back home or to please his superior officers, whom he often treated with the infantryman’s irreverence; not cruelly or unjustly, but poking them when they needed pokin’. He said, “If you’re a leader, you don’t push wet spaghetti, you pull it,” and the troops knew exactly what he was talking about.

I need 1,000 more words and don’t have ’em. Mauldin stayed up front through Normandy and on to the end of the war, right along with Willie and Joe. When generals demanded Bill’s cartoons cease, their boss, General Eisenhower declared, “Mauldin draws what Mauldin wants,” and closed the matter. In 2003, as Bill lay dying, first dozens, then hundreds of old infantrymen made pilgrimages to his bedside. They remembered, and so should we.

His book “Up Front” is still out there. I recently found two original 1945 copies for under 10 bucks each. You can go cover-to-cover in one day — perhaps on the 11th of November?

Connor OUT

Subscribe to GUNS Magazine