The M1A1 Paratrooper Carbine

A Gun For A Sandwich...

In December 1942 when this rifle rolled off the lines, World War II raged across the planet. With the crystalline clarity of hindsight, we know about things like Midway, the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot, D-Day, the chaotic last days in the Fuhrerbunker and the two atomic bombs. At the end of 1942, however, nobody knew how it would all turn out. The free world was in an existential fight for survival — that liberty might prevail was anything but a sure thing.

War Footing

The Inland Manufacturing Division of General Motors was established in Dayton, Ohio, in the former Dayton Wright Airplane Company factory. In 1922 they began producing wood-wrapped steering wheels for cars. In 1941 with the world aflame, Inland tooled up to make M1 carbines. Inland was one of nine major manufacturers who ultimately produced some 6.1 million guns. At the apogee of production, the United States was churning out 65,000 of the lithe little rifles every day.

In addition to the guns themselves, Inland produced much of the tooling used by the other contractors. As a result, there is a little Inland secret sauce sprinkled over the entire carbine world. In addition to carbines, Inland also produced tank tracks, airplane parts and sights for anti-aircraft guns.

By war’s end, Inland had produced nearly 2.5 million carbines. These included 1,984,189 standard rifles, a half-million selective-fire M2 versions, 811 M3 (T3) night-fighting carbines and 140,000 M1A1 paratrooper variants. Modern carbine collectors get the vapors over such stuff as flat bolts, checkered safety buttons and barrel bands. The good folks who made these things didn’t care. They were throwing these guns together from massive parts bins as fast as they could roll them out the door.

Wartime paratrooper carbines were made by Inland in two major runs. They started the first lot of roughly 71,000 in October of 1942. This series was produced alongside the standard rifles and ran through October of 1943. They typically sported high wood (no bolt carrier raceway cut on the lower receiver) stocks, fat pistol grips, L-shaped flip sights and push-button safeties. The month and year of manufacture was stamped into the barrels toward the muzzle.

The second run kicked off in May of 1944. These later guns featured low wood stocks and improvements like adjustable rear sights and rotating safeties. Very few carbines were made during WWII with Type-3 barrel bands that included a bayonet lug. However, those are just generalities. The folks churning these guns out weren’t much concerned about collectors’ provenance. They were trying to win a war.

Particulars

The M1A1 paratrooper carbine was designed to be more compact and portable for use by airborne forces. These guns were typically issued with a padded jump case for protecting the rifle through the rigors of parachute operations. This case hung from a trooper’s belt like a holster. The muzzle end strapped to the ankle. After a few horrible leg injuries, airborne troopers often just tucked the compact little rifles behind their reserve chutes.

The basic chassis is common between the standard and paratrooper versions. The only practical difference is the folding stock assembly. This component consists of a heavy wire buttstock with a spring-loaded pivoting buttplate and leather cheek rest. There is a holder for a small oil bottle in the cheek rest and a wooden pistol grip built into the stock.

The front sling swivel is the same as used on the standard rifle. The rear swivel is mounted to the bottom of the pistol grip. There is an inlet cut into the left side of the stock to accommodate the cheek rest when folded. The bolt carrier raceway can be either high or low wood as is the standard stock.

The biggest problem with the M1A1 paratrooper carbine was that the buttstock was not positively retained. There was a spring-loaded detent sort of holding it in place, but vigorous activity could easily cause the stock to fold unexpectedly. Small unit combat operations were the archetypal vigorous activity.

Like the standard rifle, the 7.62x33mm straight-walled carbine round pushed a 110-grain FMJ bullet that was technically effective out to 300 meters or so. Most WWII veterans who used the carbine for real respected the little gun’s maneuverability but admitted that it often took two or three rounds to get the job done.

Does It Have a Story?

My own gun collection is broad but shallow. I hunt for one good example of most everything and then move on to the next conquest. My M1A1 was a serendipitous Gunbroker.com find.

Though I am not a proper carbine collector, I do speak the language. As a result, I haunted Gunbroker for a couple months watching paratrooper rifles come and go until I found one with the right features. Once I landed the gun, I emailed the owner as I always do and asked if the gun had a story. Wow. I didn’t see this one coming.

My carbine is dated December 1942 and has all the right cool-guy stuff for a legit first-run rifle. The serial numbers for paratrooper rifles were not documented during the war, but this one is in the 130k range, which is right for the era. As carbines typically rotated through the rebuild process toward the end of the war and were corrupted with late-model parts, an original pristine unmolested original carbine can be hard to find. These early guns typically made it into circulation when they were brought home by the veterans who used them during the war.

It was a Sunday afternoon in the Texas panhandle, and it was Texas hot. The man, his wife and teenaged son were enjoying lunch after church when there came an unexpected knock on the door. They weren’t expecting company, but this was 1951. Nobody imagined that anyone might be up to no good. The man just opened the door.

He was greeted by the sight of a scraggly drifter. The vagrant was crossing the panhandle on foot and looked the part. He explained that he was hungry and had one thing of value he’d be interested in selling. He then fished around in his knapsack and produced this battered old M1A1 paratrooper carbine.

Coyotes were a problem in this part of Texas and they had only recently been discussing the teenaged son needed a farm rifle for proof against varmints. They looked this one over, noted that it was well-maintained and serviceable, and settled on a fair price. Money was exchanged, and the matron of the house threw in a sandwich and some lemonade to sweeten the deal. The drifter wandered off without giving his name.

The teenager came of age with the rifle by his side, shooting coyotes and rattlesnakes as the need arose. He had no kids of his own but eventually left the gun to a nephew along with the story of how he acquired it. The nephew kept it as long as decorum demanded, but he had no interest in firearms himself. With the assistance of a gun nerd buddy, they put the rifle on Gunbroker, and this is how it came to me.

Ruminations

PTSD wasn’t really a thing back in 1951. Some 16 million Americans donned their nation’s uniform and answered the call to beat back the Nazis and the Nipponese. When these guys came back home they were expected to just put the war behind them. Oftentimes that was easier said than done.

My wife’s grandfather was a hero of mine. He went to jump school in 1941 and served in North Africa, Sicily and Italy as an infantryman. After I finished airborne training in 1987, my then-girlfriend and I went to spend a couple of days with them at their home in Arkansas. While the ladies disappeared into the kitchen, Big Pa and I plopped down on the porch swing to talk shop.

We discussed how jump school had changed along with how it had stayed the same. He told me about Rome, Anzio and Monte Cassino. He explained what artillery did to troops in the open. He said the M1 Garand would put a man down with a single round every single time so long as you hit him center of mass. We talked for more than two hours.

Later in the evening we were sharing a meal with my girlfriend’s parents. I casually mentioned I had enjoyed the most delightful conversation with Big Pa that afternoon, and that we had discussed his time in Europe in detail. The table fell unexpectedly silent.

My girlfriend’s mom said when her dad came home he had announced that it was bad and he never wanted to speak of it again. She explained this was the first time since 1945 that her father had said a word to anybody about what he had done during the war. So it likely was with the nameless drifter in Texas, himself obviously also a former paratrooper. It’s an amazing old world sometimes.

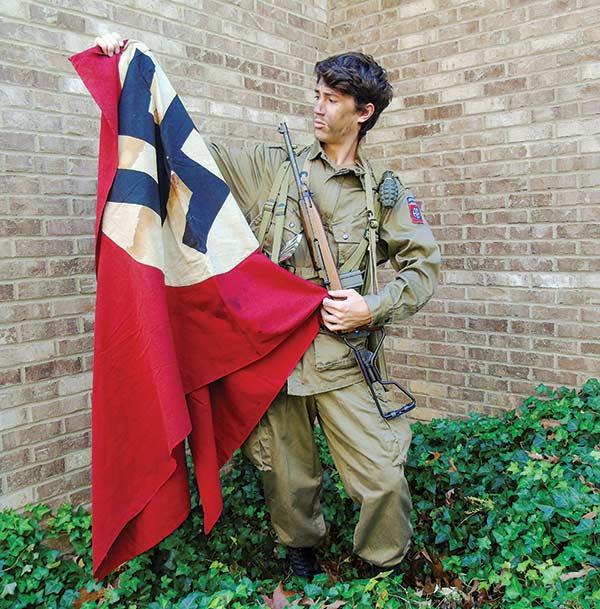

Special thanks to www.worldwarsupply.com for the cool reproduction gear used in support of this article.