Survival Of The Cheapest

Evolution and the Thompson Submachine Gun

It’s a predictable cycle. We win the war but lose the peace. The nation strains, young men die — and then there are the parades. No sooner do the street cleaners have the confetti tidied up than lawmakers start squandering the peace dividend, succumbing to the irresistible temptation to yet again expeditiously beat our swords into plowshares. When the nation is at peace it has little need of warriors. The same goes for their gear.

The interim between World Wars I and II was likely the most egregious example. The First War to End All Wars cost the planet 17 million souls. No sensible man longs to return to such stuff. Unfortunately, nations are seldom run by sensible men.

In the 1930’s we were clawing our way out of the Great Depression and had little interest in European affairs. Our involvement had relatively recently ended one global war, and we figured once would be adequate. It turned out this was not to be the case.

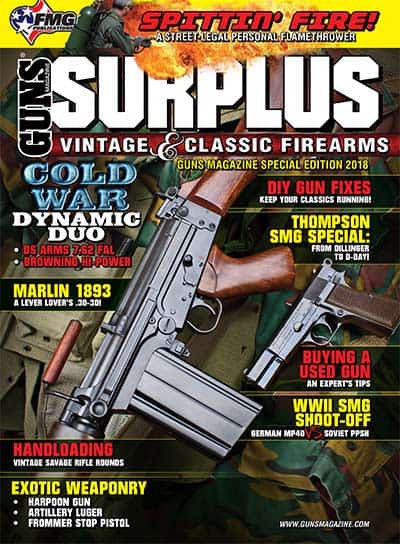

The Nazis started beating war drums in earnest in 1938. By 1940 the Germans had their Bf109 Messerschmitt, MP40 submachine gun and PzKpfw Mk IV tank. The Brits were flying those beautiful Spitfires. The Japanese fielded their formidable A6M Zero. Surrounded as we were by two magnificent oceans, we had little interest. While the M1 Garand was a gleaming exception, we Americans hadn’t invested a great deal in modernizing our ground pounders’ arsenal during the 1930’s. Then overnight everything changed.

A World Aflame

December 7, 1941, was a brilliant blue Sunday. In Honolulu it was the sort of perfect day defining such a perfect place. At 0755 the first Japanese planes dove on Battleship Row. Two hours later the entire world was at war.

Initially this was a come-as-you-are show. In no other weapon system was this made more overtly manifest than in American submachine guns. Our armaments industry went from stagnant to full throttle the moment the first Japanese bomb detonated, but we had some catching up to do.

John Taliaferro Thompson built his esteemed submachine gun to fight the previous war. The Thompson was a first-generation SMG. This means these weapons were cut from big chunks of forged steel using the tools and techniques the luxuries the prewar years afforded.

Thompson contracted production of the first 15,000 copies to Colt’s Patent Firearms Manufacturing Company, and this original Model 1921 was a thing of grace and beauty. Sporting meticulous workmanship and a stunning blued finish, the M1921 established a new paradigm in military weapons. With a top-mounted actuator and drum magazine, the M1921 Thompson was as sexy as it was lethal.

The 1921 and 1928 models were almost identical. The 1928 had a heavier bolt actuator and a slightly slower rate of fire, but they were both equipped with a detachable buttstock and vertical foregrip. The iconic image cut by these classic buzz guns kept a generation enraptured at the Saturday afternoon Bijou.

For all their geriatric shortcomings, the Thompson guns were indeed proven designs. However, the military had up until this point not shown a great deal of interest in General Thompson’s gun. Evaluations by the Infantry Board, the Cavalry Board and the Army Air Corps in the early 1920’s were uniformly scathing. Derogatory opinions orbited predominantly around the .45 ACP round’s modest range. The Infantry Board declared the pump-action 12-gauge trench shotgun to be a more admirable weapon. As is so often the case, into this self-important bureaucratic artificiality the real world soon intervened.

The Navy bought 50 in 1927. As late as 1938 the US Army was still acquiring a few Thompson guns for limited use in armored vehicles. However, these were hardly the sorts of numbers to keep a gun company reliably in the black. With war looming a shrewd businessman named Russell Maguire bought Thompson’s struggling Auto-Ordnance Company, renamed the entity Maguire Industries and ultimately made himself terribly rich.

A Surge In Demand

Germany’s Wehrmacht invaded Poland on September 1, 1939. Two days later Great Britain and France declared war against Germany. Desperately short on arms, both these governments approached Russell Maguire, hats in hand, begging passionately for guns. Maguire contracted with Savage Arms in April of 1940 to begin production of the Thompson submachine gun after an 18-year hiatus. The French bought 6,000 Thompsons, only half of which were delivered by the time France capitulated. By 1941, the British inked 11 contracts for a total of 108,000 Thompsons along with spares, magazines and accessories. It turned out the negative opinions of the US Army Infantry Board in 1922 were not universally held. The world suddenly could not get enough Tommy guns.

Nobody knows exactly how many British Thompsons ended up at the bottom of the Atlantic courtesy of the Nazi U-boats, but it was a lot. Considering the Brits were buying these things with gold from their national treasury makes the loss of these critical weapons all the more poignant. Britain was literally liquidating its national inheritance to buy them.

The 1928A1 variant was the definitive production model at this time. It differed from the earlier 1928 in some trivial aspects like ejector design and a black oxide military-type finish. Almost all of the 1928A1 models sported a horizontal foregrip.

By 1942 production of 1928A1 Thompsons reached 40,000 copies per month. When we entered the war we churned out these guns not because they were the best weapons we could produce. We built Thompsons because, thanks to the French and the British, we were already tooled up to do so.

Foundations

The details are labyrinthine to say the least. True Thompson acolytes will no doubt burn me in effigy, but the Thompson gun really falls into two basic categories. The early military model 1928A1 was, at its heart, essentially the same gun Dillinger used to shoot up his banks. The actuator was mounted atop the receiver, the magazine well was cut to accept a drum, the buttstock was easily removable and the muzzle sported a Cutts compensator. Additionally, the fire selector switches were milled steel, the barrel was finned and the Lyman rear sight was ludicrously over-complicated. The bolt also incorporated a Blish lock.

The Blish lock was the 1920’s metallurgical equivalent of snake oil. Based upon the tendency of dissimilar metals to exert predictable frictional effects when under pressure, the Blish lock required some contorted millwork to fit into the Thompson receiver. Ultimately somebody thought to run the gun without its complicated bronze Blish lock and found it worked just fine. In fact, a British field modification during desert operations involved grinding the ears off of the Blish lock to make the gun more reliable. As a result, when things got tight, the Blish lock was the first antiquated feature to go.

Evolutionary Morphology

By late 1941 it became obvious the Thompson gun would have to be mechanically simplified to meet its lofty production goals. In 1942 the 1928A1 cost the government $70 apiece. By comparison a Browning 1919A4 belt-fed machine gun set Uncle Sam back $55.25.

The engineering arts had advanced to the point where much more efficient stamped guns were possible. However, we were already tooled up for Thompsons, and momentum is tough to overcome when grappling to the death with the Axis.

Gone were the Blish lock, finned barrel and Lyman mechanical rear sight. Designers moved the charging handle to the right aspect of the receiver and fitted a simplified horizontal forearm and basic peep rear sight. The muzzle was left unadorned. The resulting guns were redesignated the M1 and M1A1. The M1 sported a floating firing pin. The M1A1 sufficed with a simple dimple in the bolt face.

Drum magazines were heavy, complicated, noisy, expensive and unreliable. As a result, the M1-series guns were not cut to accept them. The M1 Tommies fed solely from either 20- or 30-round double-column stick magazines. Unlike the earlier versions, the buttstock on the M1 Thompson could not be removed. Simpler and cheaper was the theme throughout.

When the dust settled we built about 1.5 million Thompsons before supplanting them with M3 Grease Guns. Compare that to 1 million German MP40’s and 6 million M1 Carbines. Although the prices fluctuated by contract, in 1942 the government paid about $43 for an M1 Thompson. That’s about $669 in today’s dollars.

Apples To Apples

Running these two guns side by side was an illuminating experience. I had run several thousand rounds through the M1A1 Thompson before I fired my first shot through its predecessor, the M1928A1. The differences between the two guns were surprisingly stark.

The M1A1 is fast. Its published rate of fire is 700 rounds per minute, and more than a few wartime guns were rejected as having a rate of fire too spunky for spec. The weapon remains nonetheless remarkably effective. It thoroughly spanked both the Germans and Japanese in the Greatest Generation’s capable mitts. It does, however, require some attention to technique to hit anything with it consistently.

The line of recoil is well above the buttstock vector into the firer’s shoulder. This means the gun tends to climb when firing bursts. To hold the gun on target during full auto fire requires you lean your body weight into the gun and mind the trigger closely.

By contrast, the earlier 1928A1 runs at around 600 rounds per minute. While this may not seem like much of a difference, its practical effect is huge. Short bursts are easier to manage, and mastering muzzle rise, while still an issue, seems a somewhat simpler chore. Additionally, for reasons I cannot readily ascertain, the M1928 bolt cycle just seems somewhat smoother than the later version. Cocking each bolt sequentially reveals the M1A1 sounds like a submachine gun, while the 1928A1 sounds like a sewing machine.

Interestingly, both Thompsons really run best from the hip. The guns are painfully front-heavy, and this is likely the only thing keeping muzzle rise from being an insurmountable problem. However, with enough ammo on tap a Tommy Gun managed from the hip will quite literally fill a room with lead. So long as collateral damage is not a serious concern the Thompson in both guises is a formidable close-combat tool. Both guns remain painfully heavy, particularly with a basic load of ammunition.

Ruminations

The M3 Grease Gun cost a fraction of what the M1A1 Thompson might and, hate me if you must, was really the better combat implement. The Greaser was lighter, slower and more forgiving of filth and grime. We could churn out three Grease Guns for the price of a single Thompson, and production was hugely faster.

Russell Maguire’s company was ultimately recognized as being among the top 10 percent of all war materiel suppliers. Despite the gun’s complexity, Maguire Industries was consistently on time and on quota while providing exemplary service producing spare parts for both the Americans and the British. Maguire got rich the old-fashioned way, by providing a great product along with superb customer service at a particularly desperate time.

The German MP40, British Sten, and Soviet PPSh were all easier and cheaper to produce than the Thompson. But America in those hard early years of war was not necessarily a model of efficiency. We were instead big, loud and dangerous. Our primary submachine gun was therefore a splendid reflection of the personality and character of the remarkable nation that produced it.

Special thanks to www.worldwarsupply.com for the cool replica gear used in the production of this article.