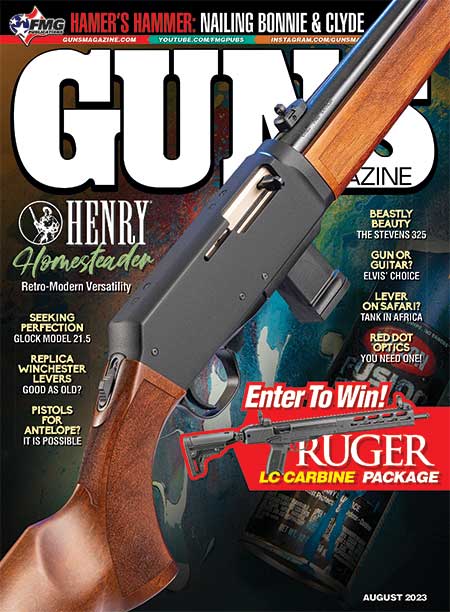

Stevens Model 325

Sometimes “Good enough” Is Good Enough

Currently, demand for firearms and ammunition is so strong many products are hard to find and expensive when they are found. Ammunition and reloading components seem in particularly short supply. It could be worse and in the summer of ’47 it was worse.

What We Want

Jack O’Connor was shooting editor for Outdoor Life magazine during WW II. By the end of the war he was getting around 3,500 letters a month, mainly from military personnel. In The Last Book, he wrote: “During WWII I found out what the sailor standing a lonely watch thought about. I also discovered what was on the mind of the G.I. in his foxhole, the fighter pilot in his P-51. It was not that cute girl next door. It wasn’t the boys at the bowling alley. It was not Mom’s apple pie. It was guns and hunting!”

Larry Koller’s excellent book Shots at Whitetails was published in 1948 and illustrates the tremendous demand for hunting firearms. “The writer began this chapter [on firearms] just before Pearl Harbor hit all of us … the [postwar] demand for firearms is so great there seems to be little need for new designs … all the arms plants are concentrating production in the few models most suited to supply the greatest need … Demands are so great … many hunters will be without their new rifle when deer season rolls around … Stevens-Savage has announced a new light bolt-action .30-30 in the low-priced field … it looks and handles as a deer rifle should….”

The rifle was the Stevens Model 325 in .30-30 Winchester. The 325 was the lowest-priced, American-made new center-fire rifle at the time, retailing for around $38. If this sounds ridiculously cheap, remember the average worker at the time earned $50 to $60 a week.

With the 325, Stevens made use of manufacturing methods such as stamped parts. Production of older models used skilled labor and considerable hand fitting. Firearms made in the ’30s — when only the best workers kept their jobs and had no incentive to speed production — were very well made indeed.

In the postwar-era, expanding production was difficult. It takes time to train skilled workers such as tool and die makers. In the booming postwar economy, a skilled worker was in great demand. Gunmakers were hard pressed to keep the workers they had.

Savage Reproach

The Stevens 325 drew a lot of criticism from rifle enthusiasts. Some said it couldn’t be very strong as it had only one forward locking lug. Actually, the lugs on many twin-lug actions don’t bear evenly — the action locks mainly on one lug. A lot was learned about steel alloys and heat-treating in WWII. With the base of the bolt handle serving as a safety lug, the Stevens was certainly strong enough for the cartridges it used.

Other critics said the rifle was just plain ugly. I have to say they had a point. Though nicely made and finished, the stock looks a bit odd. The stamped trigger guard/magazine-well assembly bolted to the stock is hardly a thing of beauty. The trigger assembly was made of stampings and not readily adjustable. At best, it was “good enough.”

The designers did not appreciate how profoundly scope sights would take over. The 325 had no provision at all for scope mounting. It was only in the last 325C series where the receiver was drilled and tapped for a receiver sight, the Lyman 40. A side scope mount for the subsequent model Savage 340 could be fitted but required a gunsmith to drill and tap the receiver.

On the 325A, the bolt face has dual spring-loaded extractors, not beautiful but they work, while providing controlled round feeding. Ejector is a spring-loaded, pivoting design attached to the receiver, with the bolt face slotted for the ejector. The shooter has control of the cartridge case throughout the feeding/extraction/ejection cycle.

Move Along

After the war, Savage began moving its manufacturing facilities from Utica, NY to the Stevens site at Chicopee Falls, Mass. Later they established a facility at Westfield, Mass., a few miles from Chicopee Falls. In The Rifle In America, 1948, Philip Sharpe wrote “… during the late summer and fall [1946] Savage trucked all machinery to the Massachusetts plant … full production of Savage rifles should be under way by January 1947.”

How many Stevens 325 rifles were made, no one seems to know. They were not serial numbered and I can find no accurate records. Beginning in 1950, Savage made some minor changes and began marketing the rifle as the Savage 340. Most obvious was the bolt handle that was changed to a more conventional appearance with a grasping ball. Initially marketed in .22 Hornet and .30-30, Savage later added the .222 Rem., .223 Rem. and .225 Win.

Ammo shortages were even more critical but didn’t seem as big a concern. Hunters in those days expected one box of cartridges to last them several seasons. They likely would go through 150- to 200-rounds in a lifetime. These days shooters seem unhappy unless they have a few thousand rounds stockpiled!