Guns For The

Great Wide Open

What Works In A Pennsylvania

Grouse Thicket May Not Be What You

Want In The High Plains Of Montana

Plenty of upland bird hunting takes place in what many hunters would call the “wide-open spaces” of the West. Upland birds in less-open spaces—especially in the East—are not doing as well, thanks to changes ranging from “clean farming,” with less brush left for bobwhite, to white-tailed deer so numerous they’ve nibbled away the smaller plants ruffed grouse need for nesting and food.

Much of the country farther west retains more “diversity” (the modern buzzword). It’s also friendlier to birds from other continents, especially chukar and Hungarian partridge, which evolved in drier, more open parts of Eurasia. Along with North America’s own open-county gamebirds—sharp-tailed and sage grouse, prairie chickens and Western quail species—chukars and Huns provide a lot of good hunting and eating.

When Eastern hunters head West they often find their light, open-choked bobwhite or ruffed grouse gun isn’t the ideal tool—except, of course, for hunting Western bobwhite or ruffed grouse. But many other birds are more effectively hunted with shotguns with longer barrels, tighter chokes and a little more weight. The weight caveat may seem counter-intuitive, because open-country upland hunting often involves long hikes, but shotguns swing smoother when there’s more heft, especially out front.

I learned this lesson over 30 years ago when an acquaintance from Connecticut sold me an Aguirre y Aranzabal XXV with 25-inch barrels. I’d always wanted a nice, light side-by-side, and the sidelock AYA not only had nifty engraving—including some tasteful gold inlays—but only weighed 2 ounces over 6 pounds!

It was one of the best ruffed grouse guns I’ve ever owned, and yes, Montana’s mountains have plenty of ruffs. (Grouse hunters east of the Mississippi may not believe this, but ruffed grouse do live coast-to-coast.) The AYA worked great for snap shots at forest birds, but for open-country shooting it pretty much sucked, at least for me. Why? On crossing shots my swing often slowed just enough to miss behind.

At my physical peak I stood 5-feet-9 and weighed a fairly muscular 180 pounds and had pretty quick reflexes. Today I’ve shrunk an inch in height, often struggle to stay close to 180, and those reflexes have slowed. Maybe I could shoot the AYA better today, but I’ll never know, since after a few years I sold it to a willowy older friend who swings a light shotgun like Fred Astaire swung Ginger Rogers. He’s very happy with the gun, and I’m happy he’s happy.

This doesn’t mean I don’t like relatively light shotguns for much of my open country hunting, because these days it’s harder to pack around heavier ones. But I make sure they have enough barrel length out front to smooth my still semi-muscular swing. But one thing lets me pack heavier shotguns.

Slings & Sage Grouse

In 2016, fellow sage grouse loony Bob Jeffrey and I hunted an area he knew in the high sage valleys of southwestern Montana. I took one of my long-time favorite sage grouse guns—a 12-gauge Remington 870 Magnum (ordered in 1979 from, believe it or not, J.C. Penney). The 870 has since taken gamebirds from Alberta to Argentina, including more sage grouse than any of my other shotguns. It swings well and with magnum ammo it can drop big males cleanly beyond 50 yards.

The 870 is also equipped with sling-swivel studs, mostly for turkey and big game hunting (it’s also taken deer, black bear and moose). But with a magazine full of 3-inch No. 4’s, it weighs nearly 8 pounds, so I attach a sling during long hikes between springs and cattle tanks. When the telltale signs of water appear, I unsnap the quick-release swivels and put the sling in my bird vest.

On the first morning of our hunt I hiked over an hour with the 870 slung over my shoulder, eventually topping a ridge to see a stream in the wide draw below, its ankle-deep pools just wide enough to require a long stride to cross. Like most such sage-country “cricks,” the green grass along its edges was close-cropped by both cattle and wildlife.

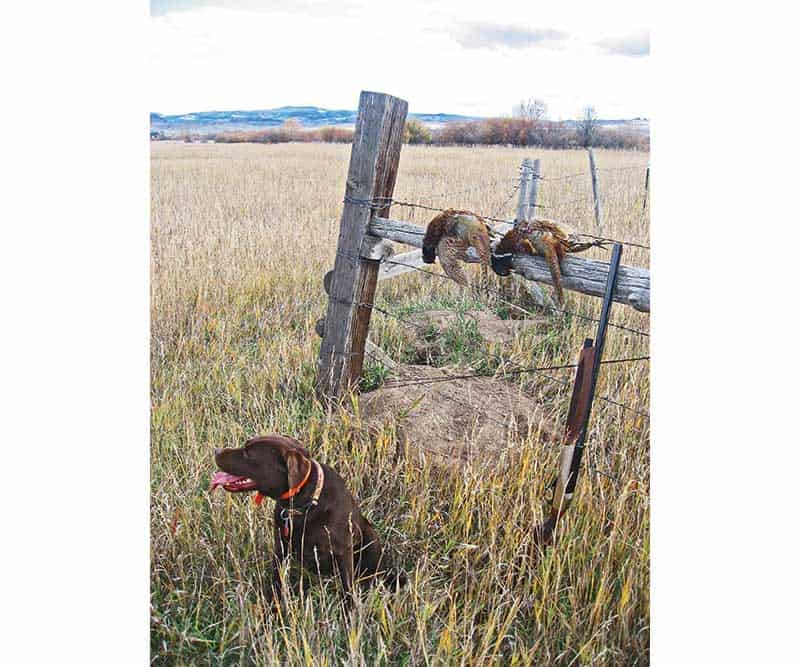

By then the morning had warmed up, and most sage grouse would be found in the shade of the taller sage on the slopes above the stream. After unsnapping the sling I followed my chocolate Lab Lena across the noses of several ridges. On the third ridge she started snuffling excitedly. Soon a sage grouse rose in front of her, its long wings whooshing rather than whirring like those of smaller grouse. I raised the shotgun and swung very deliberately, allowing the tight pattern to open up some, and dropped the bird about 35 yards out.

At the shot no other grouse rose, which is unusual because they’re social birds. In September they’re normally found in coveys of 3 to 4 up to a dozen. After Lena and I tromped around enough to make sure the bird was alone, I re-slung the gun and we went looking for more water.

Bob had headed off in another direction with his Drahthaar Maggie. I circled toward where he’d headed, since in another other hour or two, the lunchbox in his pickup would be on our collective minds (both human and canine). After a hike of nearly 2 miles, I spotted them across another wide draw containing a slightly larger stream, one bordered in places with thigh-high willow patches and scattered wild rosebushes.

After removing the sling, Lena and I hunted our way across, but again did not encounter grouse until we entered the taller sage on the next ridge. A covey of maybe 10 birds rose and I dropped one at almost 50 paces.

That’s how the hunt went for two days. We’d hike 2 or 3 miles between possible sage grouse spots, and then find birds less than half the time. That’s because there’s a lot of sagebrush surrounding each sage grouse.

Prairie Pheasant

I live in a wide, not so wide-open valley between two mountain ranges, and the 2016 pheasant hatch was the best since moving here 27 years ago. The local pheasant cover varies from short-grass prairie to streamside willow-alder thickets so tight even a muscular Lab has a hard time pushing through—and in the thickets it’s harder to hit a rooster than most ruffed grouse.

So I mostly hunt pheasants in more open country—primarily on public land—early in the morning or late in the evening when the birds are out feeding. They often flush from unexpected places (they get harassed in obvious ones). The walks don’t average quite as far as sage grouse hikes, but you still have to cover considerable country—and you’d better have the shotgun in your hands rather than slung over a shoulder.

For over a dozen years my favorite pheasant gun has been a 12-gauge SAUER Model 60 side-by-side made early in World War II. Like many German doubles, it’s choked tight and tighter, but even with its 28-inch barrels, it only weighs a couple of ounces more than my late, unlamented AYA sidelock. Since our normal pheasant numbers aren’t high, two shots are usually plenty—but when the good hatch occurred, I decided a repeater might be helpful.

In 2014 I’d acquired a Benelli Ethos 12-gauge, but aside from some clays and a few ducks, hadn’t used it much. However, it weighs only a 1/4-pound more than the SAUER and a full pound less than the 870. So I decided to see how it worked on pheasants.

Its first chance came when hunting a local ranch, thanks to a Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks program called Block Management, where they pay landowners to allow public hunting. Block Management properties tend to get considerable pressure, especially anywhere there are pheasants.

This particular ranch has one great chunk of pheasant ground—an ungrazed meadow bordered by a couple of creeks with plenty of willow-alder cover. The creek edges get hammered during the first couple days of the season and the surviving roosters hide elsewhere.

On this day I was walking across the meadow through knee-high grass, Lena in the lead, when she started snuffling hard. A rooster soon rose and at my shot the bird dropped—and a second rooster got up to the left. While Lena ran for the dead bird, I swung the Ethos and dropped the second bird too. By then I was half-expecting a third bird, and while none rose, it felt pretty good to have another round in the chamber.

After Lena brought back the first pheasant, I hand-signaled her to where the second had fallen. She grabbed it and started heading my way, but as she got closer apparently had a change of heart, turning and looking away, as if saying, “Hey, you’ve got a rooster already. This one’s mine.” She’d never exhibited this attitude before, but I can imagine giving away all the birds you retrieve eventually gets frustrating.

We soon came to an agreement, however, and two roosters in my vest felt pretty good. The Ethos took more pheasants across the fall, along with some Hungarian partridge, never malfunctioning even during late December snowstorms. It continued swinging nicely on shots that grew increasingly longer as the weather turned colder.

It pains me some to say this, but after several decades of open-country upland hunting, I’ve come to believe the boring old 12 gauge is pretty much ideal. I love the 28, 20 and 16 gauges, and even with the 28 have dropped many pheasants and sage grouse at 40 yards. But that’s been relatively early in the fall, when warmer weather and taller cover tend to make birds hold tighter. As the fall progresses, all open-country birds tend to flush further out, often rising at 30 or 40 yards—if they get up within range at all.

The ranges I mention, incidentally, are actually paced off rather than guessed. Most upland hunters guess, and not very well. A few years ago my wife Eileen and I hunted prairie chickens in the Sand Hills of western Nebraska with local bird-guide and dog trainer Mike Clark, and the first one got up well out there. I managed to drop the mature male and took 55 paces to reach where it fell. Later in the evening Eileen overheard Mike telling somebody else I’d killed the chicken at 80 yards!

While the vast majority of upland birds are killed within 40 yards, in the wide-open spaces ranges can be longer, so clean kills require not only larger shot but tighter patterns. The standard 1-1/4 ounce 12-gauge load doesn’t consistently provide dense enough patterns past 40—even on sage grouse. I prefer at least 1-1/2 ounces of No. 5 shot. And back when sage grouse season stayed open through November, I often used 3-inch magnums with No. 2 shot.

The big problem, however, is actually late-season partridge, whether chukars or Huns. They tend to flush well out there too, but their smaller size requires more pattern density. If I’m only hunting partridge, I really like No. 7 shot—an unusual size but far more effective than No. 7-1/2 at 40+ yards. However, in Hun country larger birds can be encountered, too, so often the compromise is standby No. 6 shot. Perhaps more important than the exact shot size is to seriously pattern several chokes to find out (1) exactly where the patterns land at 50 yards and (2) which chokes provide a tight—yet even—pattern.

After this, it’s most important to take your bird dog for long walks, because you’ll both be covering a lot of ground.

Sage Advice

The most open-country of American birds is the sage grouse, the largest grouse in North America and second largest in the world, (after Europe’s capercaillie). A mature male weighs 5 or 6 pounds, and occasionally up to 8.

Many native Westerners don’t like the taste of sage grouse, so don’t hunt them much since their sagebrush diet gives their dark meat a strong flavor. However, this problem is often “enhanced” through poor field care.

Many hunters toss un-gutted birds into the bed of the pickup with the Hi-Lift jack, empty Mountain Dew cans and other essentials of existence in wide-open spaces, cleaning them at the end of the day. But quick field dressing can make sage grouse taste really good, especially in recipes combining several flavors, such as enchiladas.

Unfortunately, sage grouse seasons have been highly curtailed in the last few years due to falling populations. Some of the drop is due to habitat loss from various human factors, but studies in Idaho and Montana found sage grouse highly susceptible to West Nile virus.

Other studies have shown hunting sage grouse doesn’t affect overall numbers—partly because relatively few people do it—but seasons were reduced anyway. Montana’s season used to run from September 1st into October or November, but is now limited to September when the weather’s usually warm. Consequently, birds are normally found near very scattered water sources, so you can look forward to considerable hiking.