Safeties: The Good, The Bad

And The Ugly

Like them Or Not. They're Here To Stay

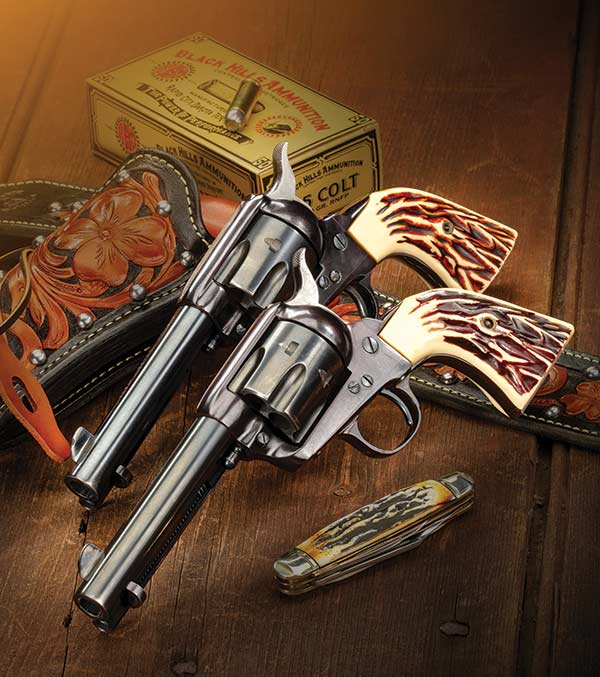

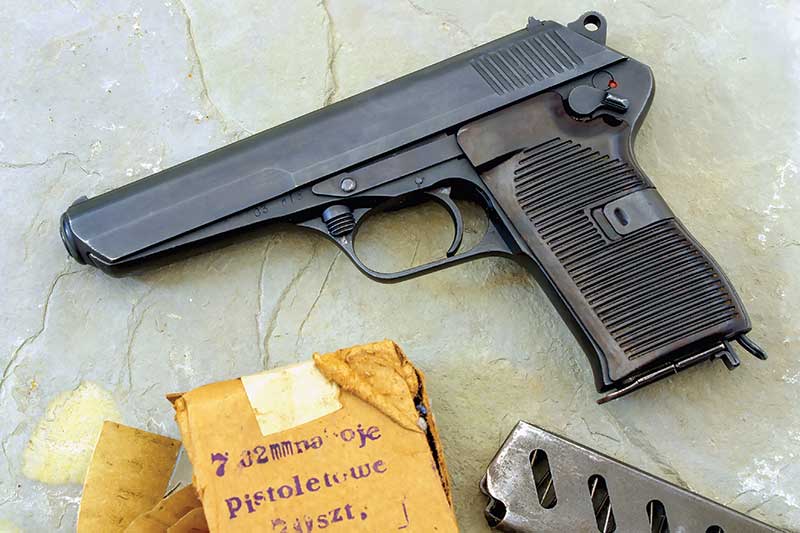

Attempt to make some CZ-52s “safe” by pushing up on the decocker

and instead, it will fire the gun! Ever wonder why the design was mothballed

after only four years? The cross-bolt safety (left, top) is simple and mostly

idiot proof. Push “in” as a right-hander to make the gun ready to shoot.

The hammer block safety of the S&W revolver (left, bottom) renders the

hammer incapable of reaching the primer unless the trigger is depressed.

I would imagine many GUNS readers have seen the film Black Hawk Down. There’s a scene of note where Eric Bana, playing a Delta Force ass-kicker, is chastised by a superior officer for his M16 being off-safe. Bana holds up his index finger and flexes it in front of the commander’s nose. “This here is my safety,” he replies. It’s a funny line, though it’s become the bane of range officers just about everywhere.

For many gun owners, firearm safeties represent a mechanical solution to what they consider a non-existent problem: Flipping a piece of metal up or down does not excuse the shooter from the responsibility of obeying the “four rules” of firearm safety and cannot take the place of situational awareness and common sense. To others, some safeties represent intrusion of the nanny state, bean counters and lawyers into the world of firearms product development. For these shooters, each device foisted on the buyer seems to be intrusive proof that someone, somewhere, has capitulated to the enemies of the Second Amendment.

And yet, we live in a world where accidents can and do happen, even to good and responsible people, and Murphy’s Law is absolute. Ask someone who’s been around guns as part of their career, and they will be able to tell you at least one story where some kind of safety has prevented serious injury or death.

The truth, then, is somewhere in the middle. Safeties, as a whole, cannot be dismissed as either wholly unnecessary or reprehensible, nor can they be relied upon as the sole mechanism to prevent negligent or unintentional discharges.

That said, some designs are certainly better than others.

The Good

In general, I’m a fan of what we might call “passive” safeties, which work behind the scenes without most shooters being aware of them, almost like a guardian angel. A great example of this is the system on the Beretta 92, starting with the “SB” models of the early 1980s and carrying into today’s “FS” line: the firing pin block safety. When the trigger is pulled, a block literally raises up and out of the way of the firing pin, allowing the pin to come forward only when the trigger is rearward.

Additionally, I like the ingenuity of the S&W revolver hammer block, where once again a piece of metal drops out of the way to allow the firing pin access to the primer only when the trigger is pulled. Here, the design solution is simple and elegant, thanks to the geometry of the lock work. Most users have no idea what job this little piece is even doing.

I also very much like decocking systems. Everyone’s comfort zone is different, but I feel most comfortable carrying loaded firearms when neither the firing pin nor hammer is being held under spring tension. For this reason, I tend to like a good number of “traditional” double-action autos.

Consider the Sig “P22X” series of handguns as representative examples of the type. Once loaded and safely decocked, the hammer is held away from the firing pin. From there, one must load the mainspring with enough potential energy to bust the primer, either by cocking the hammer, or more likely, through a long and deliberate DA trigger pull.

Beyond this, a good number of “active” safeties tend to work for me. On most rifles and shotguns, I like a simple cross-bolt style. Usually, these safeties are effective, simple and intuitive. Most work for right handers by pressing “in” toward the gun to disengage them. Tang safeties are also generally good and intuitive, where back is “safe” and forward is “fire.” Not always, mind you, but the design language is relatively standardized.

The Mediocre-To-Bad

On the other hand, many safeties run contrary to what we’re used to or to industry “best practice.” For example, slide-mounted safeties on autos are always a headache, requiring shifting grips or reaching up to a weird part of the gun to activate or de-activate it. And even then, is it up to fire, or down to fire?

Other safeties require doing some homework to operate and “read” at a glance. Many rifle safeties are guilty of this, especially when they feature levers or twist-knobs or little flags to monkey with. Beyond anything but range use, my advice here is to pay attention to these configurations well before you really need to use them. Imagine your quarry bounding away on a hunt because you’re fiddling with a flap of metal at the rear of the gun! If you have to hunt for an “S” or an “F,” it isn’t intuitive.

I’ll also say something heretical here: I don’t love the 1911 thumb safety. The control is positive and certainly works as intended. However, experts have opined a “low thumbs” grip introduces the potential to knock the safety upward under recoil. As such, the modern school of thought is to ride the safety with the dominant thumb. Me, personally? I don’t like any of my digits to be close to the sharp edges of reciprocating pieces of metal.

The Ugly

Some safeties are anything but — using them may actually increase the risk of a negligent discharge or personal injury! For example, let me tell you about the decocker on my military surplus CZ-52.

Before ever engaging this control, new owners are advised to perform the “pencil test:” Unload the gun, put a pencil in the barrel so the eraser rests on the breech face, and thumb the decocker. Your gun may act like mine, which is to say it will launch the pencil right out of the barrel! Phrased another way: The “decocker” can act as a second trigger. Any wonder why the design was unpopular?

Beyond that, some guns have safeties in ill-advised places. On my Stevens 520, the gun utilizes a “suicide safety,” where the lever is located within the trigger guard. Similarly, I don’t like the safety on my M1 Carbine, which requires flicking a lever back toward the trigger to engage the control. Reaching for these devices quickly could cause a problem!

Needless to say, even some of America’s most iconic firearms and storied designers sometimes get the details wrong.

The Ultimate Judge: You

Broadly, I would say a safety will provide value to you under two broad conditions — First, if you understand how it mechanically impedes a round from being fired, and second, if you trust it to work if your gun is dropped down a flight of concrete stairs. A safety is all the better if it seems intuitive, easily engaged (but not too easily engaged), and reachable with a finger or thumb from a natural firing grip.

Those are my “wish list” items, but again, I’ll note they’re not for everyone. To paraphrase our own Massad Ayoob, some users may not actually want a gun that can be “intuitively” made ready to fire: Consider a felon snatching an on-safe gun from an officer’s holster. Would it be a positive thing for such a ne’er-do-well to operate the policeman’s gun fumble-free?

As such an example proves, context and usage parameters are just as important as any elements of consumer design when it comes to safeties. Before choosing any firearm for serious work, it’s important to understand and be comfortable with all of its controls, not just the trigger.

Of course, there will be some who still don’t think any mechanical safety is useful. To those readers, I’ll say this: I’ve yet to drop a gun. I have, however, spilled quite a few cups of coffee, stubbed my toe on all manner of things, and experienced a number of critical mechanical failures while using everyday objects.

Such mundane occurrences are reminders that shit happens, and speaking personally, I have a soft spot for firearms whose safeties are thoughtfully designed for exactly that kind of world.