Ruger's Old Army

The percussion revolver era lasted basically from the advent of the first successful revolver, Sam Colt’s 1836 Paterson, to the Colt 1861 Navy and late model Remingtons. Legendary sixguns such as the Colt Walker, Dragoon, 1851 Navy and 1860 Army; the .36 and .44 Remingtons; and even such oddities as the LeMat, which added a shotgun barrel to the equation, were used by gunfighters, cowboys, lawmen, soldiers, anyone who had need for a powerful sixgun.

Although many of these would continue in use throughout the 19th-century, the era basically ended with the coming of the S&W .44 American in 1869 and the Colt Single Action Army in 1873.

Firearms were relatively expensive, even more so than now, so there was no wholesale turn in of cap and ball revolvers when the first metallic cartridge-firing sixguns arrived. Many percussion revolvers were converted to cartridge use both by the firearms manufacturers and local gunsmiths, and most remaining examples show much use. Some conversions were very versatile sixguns as one had the choice of reverting back to cap and ball use if metallic cartridges were in short supply.

Being able to spend the day shooting hundreds of rounds and then reloading the brass in the evening is a later 20th century phenomenon. In the previous century ammunition was very expensive and used sparingly. A Winchester catalog from the 1870s priced 1,000 rounds of .22 rimfire ammunition at $8. Today 1,000 rounds of .22 Long Rifle will run around $16 if one shops carefully.

To put this in perspective, in the 1870s one had to work more than a week to buy what now costs less than an hour’s labor. You can bet the 1,000 rounds from the 1870s was not shot up in an afternoon, but rather was used sparingly for many years. For the careful shooter 1,000 rounds meant somewhere close to 1,000 rabbits, squirrels, etc for the supper table.

Frontloaders Today

The percussion era may have ended in the 1870s, however today there are probably more cap and ball revolvers in use than there were in the 19th-century. Their shooting was mainly serious; ours is mainly for sport and enjoyment. Thanks to some forward thinking individuals such as the late Val Forgett of Navy Arms we now have replicas of most 19th-century percussion revolvers at our disposal.

Bill Ruger was also a black powder enthusiast and his appreciation of the Remington pocket revolver can be seen in the little .22 Bearcat. When it was decided Ruger would offer shooters a percussion revolver, looking back to the past for inspiration would be fine, however, it would have to be a thoroughly modern revolver. Inspired? Yes. A copy? No. What Ruger did come up with was not a replica of any 19th-century revolver, but rather a completely new design.

Bill Ruger wanted any cap and ball revolver that bore his name to be as strong as the Super Blackhawk and at least as accurate. He had no intention of building anything except a “top strap” revolver such as the Remington rather than the much weaker open-topped Colt style. Harry Sefried was the head of the project to come up with Ruger’s 20th-century version of the 19th-century percussion revolver and they certainly did just that.

Based on the three-screw Rugers that were being produced at the time, the Old Army, as it would be known used the same basic action and grip frame. Unlike the 19th-century revolvers, Ruger’s version would have all coil springs — mainspring, hand spring, and bolt spring — as found on all Ruger single actions since that first .22 Single-Six arrived in 1953.

The loading lever, rammer, and base pin of the Old Army are linked together and held in place by one large screw that is easily locked or unlocked by using a coin such as a penny. It exerts the best leverage in seating the ball over the powder of any percussion revolver ever produced. The Old Army also has an excellent locking latch under the barrel to secure the loading lever. I have never had the loading lever come loose under recoil in shooting any Old Army.

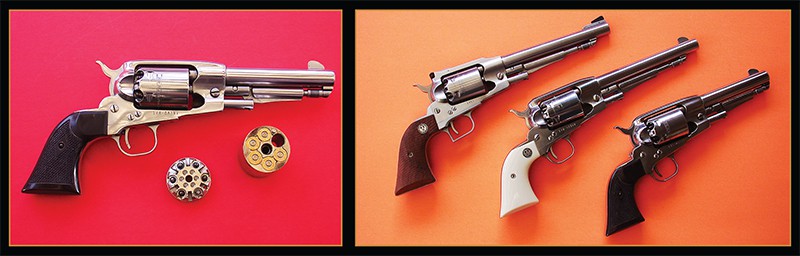

The Old Army was first produced in 1972 and until very recently was only available as a 7 1⁄2-inch blued or stainless steel version with adjustable sights. It is very popular not only for general shooting but is also a proven winner at the firing line in black powder matches.

One Tough Gun

I purchased one of the very early stainless steel Old Army revolvers as that finish makes cleanup after shooting black powder or a black powder substitute so much easier. That original revolver has been in use for over three decades now and is just as good as ever. The nipples have had to be replaced several times but it still performs better than I can.

I made a swap very early between my Mag-Na-Port Custom three-screw Super Blackhawk and the Old Army. The Super Blackhawk grip frame was larger than I needed on this smallish .44 Magnum, so I simply swapped grip frames and triggers with the Old Army. The handling qualities of both revolvers were greatly enhanced.

This is one percussion revolver that can be carried safely with six rounds as there are safety recesses between each chamber for resting the hammer. They should always be used unless the hammer is resting upon an empty chamber. Stainless steel nipples are set deeply into the cylinder to help prevent fragments of fired caps falling into the mechanism or behind the cylinder thus causing a jam. This has never occurred with any Old Army revolver I have used.

The Old Army is also the only percussion revolver that can be dry fired as the hammer nose is designed to clear the nipples by .005″. The Old Army also bears the distinction of being the only Ruger single action that still has the old-style mechanism of the Flat-Top and three-screw Blackhawks rather than the New Model transfer bar.

Ruger proof tested the prototype Old Army by seating a round ball on top of the cylinder full of Bullseye. If such a test were tried using a cartridge case and bullet in almost any revolver results would normally be disastrous. The Old Army held, however it should be fired only with black powder or black powder substitutes and never with smokeless powder.

Ruger's New Version

With the tremendous rise in popularity of Cowboy Action Shooting especially in the decade of the 1990s, Ruger saw a market for a traditionally styled percussion revolver for competition which does not allow adjustable sights. The basic Old Army stayed the same except for the Vaquero treatment. That is, the adjustable rear sight was removed, the top strap rounded and given the old-style hog wallow rear sight groove, and the ramp front sight was replaced by a traditional blade.

Shooters who prefer to stay authentic use replicas of such early percussion revolvers as the Colt 1851 Navy or 1860 Army or the Remington New Model Army. Those who want the best possible percussion revolver when it comes to function and accuracy as well as easy cleanup go with the Ruger fixed sighted Old Army. This version is also available in both blued and stainless finishes and only a 7 1⁄2-inch barrel. At least, until now.

New for 2004 from Ruger was a fixed-sighted, stainless steel or blue, 5 1⁄2-inch Old Army. The only basic difference, other than barrel length, from the original long barrel versions, is the fact that the loading lever mechanism cannot be removed without unscrewing the catch from the bottom of the barrel. Standard grips on the 5 1⁄2-inch Old Army are faux ivory with the Ruger Eagle medallion.

Favorite Stocks

Shooting black powder does become a little messy and my hands tend to get a little slippery when using a Thompson lubed wad between powder and ball or placing lube (I use Crisco), on top of the seated ball. This situation did not mate up well with the slippery ivory grips, so my pair of Cowboy Action Shooting-5 1⁄2-inch Old Armies now wear checkered buffalo horn Gunfighter stocks from Eagle grips.

The dark horn color provides a nice contrast to the stainless steel finish, while the checkering prevents the slipperiness, and the gunfighter style shelf at the top of the grip panel provides extra security and prevents the revolver from shifting in the hand while fired. This could be a concern with a heavy recoiling .44 Magnum, however even the heaviest black powder loads in the Old Army exhibit no more recoil than a +P .38 Special.

I prefer to shoot these Old Armies with a full house load using a 40-grain by volume measure. A Thompson lubed wad is seated over the powder, and then a Speer .457″ round ball is rammed home. The extra leverage on the loading lever is really appreciated when using this much powder.

After all chambers are loaded, then and only then, are CCI No. 11 percussion caps are placed on the nipples and the hammer let down into one of the safety notches if I am loading six rounds. Three different black powders, actually one black powder and two substitutes, were used in testing these 5 1⁄2-inch Rugers. Even in these short barrels, muzzle velocities are right up there.

Goex FFFg is under the SASS maximum muzzle velocity allowed for revolvers of 1,000 fps as it comes in right at 900 fps. However, shooting in cool temperatures, 40.0-grains of Pyrodex P is just under 1,000 fps and would probably go over in warmer weather. Afull house loading of Hodgdon’s new Triple-7 FFFg gave such high velocities I was not satisfied until I re-tested it. The results were the same both times with muzzle velocities in excess of 1,100 fps in cool weather.

Cartridge Convertible

At about the same time Ruger announced the 5 1⁄2-inch Old Army, Taylor’s & Co. took over distributorship of the R&D conversion cylinders for percussion revolvers offering sixshot .45 Colt cylinders for both Remington and Ruger cap and ball sixguns. My original plan was to acquire a pair of stainless steel .44 Remington New Model Army revolvers and fit them with nickel-plated R&D cylinders from Taylor’s. Before this happened I saw the 5 1⁄2-inch Old Armies and I was totally smitten.

A pair of test Rugers, which I will surely purchase, were obtained from Ruger and at the same time, an order was placed for two nickel-plated R&D Ruger cylinders chambered in .45 Colt. These cylinders are not cheap, however they exhibit excellent workmanship and are well worth the going price.

They are a two-piece affair with a typical bored through cylinder and a removable back plate. This back plate has six firing pins that look like percussion nipples. A hole in the back plate lines up with a pin on the back of the cylinder to lock the plate in place after five cartridges are loaded in the cylinder. One of the firing pins is a different color so it is always easy to locate the empty chamber.

Once the cylinder is loaded and the back plate replaced, it is then placed carefully into the Ruger frame, the base pin replaced, and the percussion revolver is now ready to be fired with metallic cartridges. With a little stretch of the imagination this allows us to be spiritually transported back to the 1870s and receive the feeling of using the original cartridge conversions.

A Good Lesson

I learned long ago to never load ammunition for a specific revolver until I have that revolver on hand and can check the load for chamber fit. Most of the .45 Colt black powder loads I already had on hand were loaded with .454″ bullets for use in Colt SAAs and replicas thereof. None of these would chamber in the tight cylinders produced by R&D. With the standard .452″ bullets chambering was not a problem.

The addition of Taylor’s R&D cylinders provides triple versatility for a pair of Old Armies for Cowboy Action Shooting competition. I now have the choice of using the same two revolvers in the Plainsmen category using the original percussion cylinders, or the .45 Colt cylinders can be used with smokeless powder in the Traditional class or black powder for Black Powder, or Frontier Cartridge class. When all this is considered, the price of the cylinders appears not to be expensive at all.

Great Leather Gear

Good sixguns deserve great leather and whether the Old Army is used for CAS shooting or just packed while roaming sagebrush, foothills or mountains, quality holsters are necessary. For this a call went out to Bob Mernickle for a special pair of Slim Jim holsters and matching belt. I wanted the trimmest, lightest possible rig.

Mernickle did a great job on these. I ordered holsters to hang straight so they could be worn butts to the front or to the rear and I also wanted a deep dark brown color to match the buffalo horn grips. I asked that no cartridge loops be supplied, again to keep this rig as light as possible. Mernickle decorated the belt with the gunfighter stitch and carried out the same motif in the holsters. This is simply an excellent rig and even more perfect for my needs than expected.

I would guess I will be carrying one of these 5 1⁄2-inch Old Army sixguns in more places than Cowboy Action Shoots. Whatever your leather needs, be it for concealment, hunting, or competition; or whether your handgun is a single action, double action, or semiautomatic, you can expect just about a 100-percent chance Mernickle can supply your needs. He is highly recommended.

Normally, I would consider firing jacketed bullets in an Old Army revolver as something akin to sixgunnin’ blasphemy. However, on the chance that someone might reach for a conversion-cylindered Old Army for defensive purposes I did try one .45 Colt defensive round. The load selected was Cor-Bon’s 200-grain JHP and a good shooting round it is! It placed four shots into 7/8 inch at 50 feet and clocked out at over 1,000 fps over the Oehler Model 35P chronograph. With results like this it would also make an excellent small game and varmint load.

The entire test results for both 5 1⁄2 inch and 7 1⁄2 inch traditionally sighted Old Armies are in the accompanying table. It is easy to see that whether using percussion or cartridge cylinder, these are excellent shooting revolvers. With blued or stainless construction, fixed or adjustable sights and now a choice of barrel length, Ruger’s Old Army can be had in many variations. Whatever version is chosen, one can be assured the best possible percussion revolver has been acquired.