Buying Used Long Guns

Here are some tips and tricks

to help make a satisfying deal

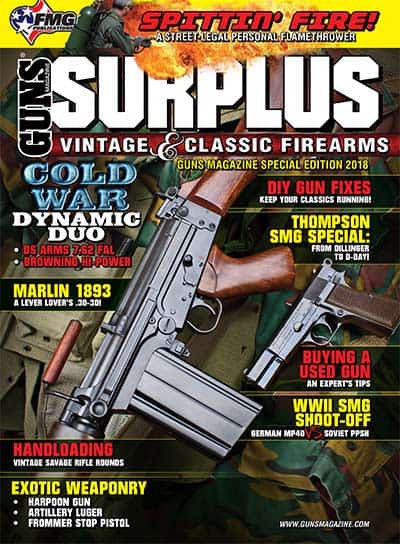

Used shotguns tend to hold their value better than rifles, since their

bores don’t get shot out. Ones in John’s collection include (from top to bottom)

a J. Venables & Son British 12-gauge, a “no-name” German combination gun

in 16-gauge over 9.3x72R, a 16-gauge Ithaca Model 37 and a 16-gauge Winchester Model 12.

One great thing about guns is they don’t wear out nearly as quickly as pickup trucks. My oldest is a “trapdoor” Springfield .45-70 made in the 1880’s. All the mechanical parts still work, and it consistently hits an 8″ gong at 200 yards with the issue iron sights. My wife Eileen and I also own several shotguns around a century old, and they all work just as well as when they were made.

That’s why there’s a thriving market in used rifles and shotguns. Anybody contemplating buying or selling many should own the latest Blue Book of Gun Values, but some people instead search the Internet for similar guns for sale. However, both the book and the Internet primarily show asking prices, not selling prices.

They also don’t reveal regional differences. My home state of Montana isn’t great for buying and selling shotguns, especially doubles, but the market in the Midwest and East is much better. Savage 99 lever actions also don’t sell nearly as well in the West as in New England. Prices even differ within states. When a gunsmith friend first opened his shop in Houston, Texas, he made extra cash by buying Ruger No. 1 rifles, then selling them in West Texas where No. 1’s were more popular.

Condition

Condition is obviously a big factor in price, and the Blue Book contains a section on assessing a firearm’s condition worth its cover price. Condition is most easily assessed personally, but something can be told by photographs provided by Internet sellers, and there’s traditionally an examination period where a gun can be returned for a refund.

The first check should be a close look at exterior condition. Big defects are obvious, but some guns have small cracks in the stock — or even in the action, though those usually occur only on shotguns. The action should also work easily. If possible use dummy rounds to check feeding, extraction and ejection. The best way to make sure it goes bang is to actually shoot, but that’s not always possible. Sometimes, however, a primed empty case can be touched off, or a brand-new snap-cap without any dent on the “primer” can be clicked.

While there’s usually some correlation between exterior and interior condition, an older rifle with a nice stock and strong bluing can have a pitted bore due to black powder or corrosive primers. In America, corrosive primers were standard before Remington introduced Kleanbore priming in the late 1920’s, but the Kleanbore compound was based on German patents already used in Europe, so the bores of many older European rifles are in better shape.

A pitted barrel isn’t an automatic disaster. One basic rule of thumb is if some shine remains, a rifle will shoot accurately, even with cast bullets, though as Mike Venturino has mentioned, a “dark” bore will often shoot cast bullets. I’ve found installing Dyna Bore Coat can help, though how much depends on the amount of pitting. Shotgun bores can also be pitted, but unless the corrosion is dangerously deep it can be polished away — or even ignored, since it doesn’t affect patterns.

Pitting can be seen with some light through the bore, but erosion occurs in front of rifle chambers, so with the exception of takedown models, erosion there can’t be examined in lever and pump rifles. Even when the rear of the barrel can be examined, however, erosion normally doesn’t become apparent to the naked eye until the barrel’s fried. At that point the bore looks slightly darker right in front of the chamber, but a bore-scope normally reveals far more extensive damage.

A bore-scope also reveals tool marks, but those don’t necessarily mean the rifle won’t shoot accurately. Many roughly machined barrels will shoot very well, and so will many eroded barrels — and moderately eroded barrels can be helped. One of my favorite varmint rifles is a Remington 700 Classic .221 Fireball bought used, with the throat eroded almost 2″. A dozen fire-lapping shots smoothed the “gator-skin,” and the rifle groups five shots into a half-inch at 100 yards.

One final caution about nice-looking rifles and shotguns: The steel beneath the stock can be rusted, sometimes to the point of being unfixable. The most notorious cases are Brownings with salt-cured wood from the 1960’s and ’70’s, but other companies also used salt wood. Older military rifles can also be badly pitted below the stock line, but any gun from humid parts of the country should be checked.

Exterior wear can be divided into two categories: normal use and abnormal abuse. When all long guns had wood stocks, some finish wear was expected, but abused stocks can be cracked or have chunks missing. Bluing normally thins around sharp edges and places often handled such as action bottoms, levers and bolt handles, but abuse includes rust-pitting, screws mangled by ill-fitting screwdrivers or even home engraving. The first pre-’64 Model 70 Winchester I owned had a previous owner’s name and town crudely etched on the left side of the action, but the rest of the rifle remained in decent shape so I bought it — at a bargain price.

However, exterior abuse doesn’t necessarily mean the interior’s been neglected. I’ve encountered a bunch of old rifles and shotguns with little finish but fine bores and actions. Many people who really use firearms know how to take care of the functioning parts, accepting inevitable exterior wear. Since walnut and steel can be refinished, I’d rather find a lightly battered gun with good guts than a nice-looking one with a severely pitted bore or malfunctioning action.

Sometimes, however, refinishing can be a mistake. Many American gun buyers value “all original” over refinished wood and reblued steel. Consequently a pre-’64 Model 70 with only 80 percent of its original varnish and blue often brings more than a refinished rifle.

This attitude isn’t as rigid with European guns, partly because so many were refinished by the original manufacturer, but some Americans get upset by modifications to European rifles. I have a “no name” pre-World War II German custom rifle in 8x57JS, with light engraving and double-set triggers, but sometime, much later, the action was professionally drilled and tapped for American-style scope mounts.

A couple years ago I put the rifle on my table at a gun show, and some guy picked it up (without asking) and went into a rant about the scope-mount holes. He wasn’t even addressing me, just the stupidity of the universe. In reality, unless a European rifle is something really valuable, such as a near-new original Mauser or Mannlicher-Schoenauer sporter, being drilled and tapped probably adds to the value.

There can also be unseen modifications. Many older rifles were rechambered to some other round without the barrel being re-marked. It’s common to find pre-’64 Winchester Model 70’s that left the factory as .300 Holland & Hollands rechambered to .300 Weatherby, one reason Model 70’s in .300 H&H bring higher prices even in “hunting” shape.

Similar stuff happens to other chamberings. A friend who buys and sells many old rifles ended up with a rare pre-’64 in 7×57 Mauser. He never shot it, just resold it at a nice profit. The guy who bought the rifle took it to the range, and fired brass came out with a much sharper shoulder: Somebody had rechambered it to 7×57 Ackley Improved. There was some back and forth over this! (I’m not even going to get into “fake” Winchesters.)

Such rechamberings were usually due to fads, but some were practical. I have a custom 1903 Springfield built by Frank Pachmayr before World War II. Originally a .35 Whelen, in the 1960’s it was rechambered to .358 Norma Magnum — and not re-marked. At the time the Whelen was still a wildcat, but these days the .358 Norma is almost as dead as a beached whale, while the .35 Whelen’s a moderately popular factory cartridge. Luckily, the rifle’s owner was the late Idaho stockmaker, Ike Ellis, an honest guy. He told me about the rechambering and priced the rifle accordingly.

Shotgun barrels are also often modified. Many British hunters take their nice doubles back to the maker after a season of shooting driven pheasants, to be refinished or tightened. Yes, fine British shotguns can shoot loose, the reason their makers often suggest frequent tune-ups. This tuning also often involves polishing bores to remove pitting, and barrel walls can become too thin for safety with higher-pressure American ammo.

Another common worry with older English, European or American doubles is short chambers. If you’re serious about buying nice old doubles, invest in a chamber-length gauge. Brownells sells the multi-gauge Galazan model for about $50 — a good investment.

However, some of the worry about shooting longer shells in short chambers is overwrought. Aside from relatively rare 12’s with 2″ chambers, most “short” chambers are supposedly 2.5″ or 2.56″ in length. Theoretically this can result in higher pressures when the crimp of modern 2.75″ ammo unfolds due to partial blockage of the forcing cone. But numerous tests have been made on 2.75″ ammo fired in 2.5″ chambers, and pressures rise only slightly or not at all.

Partly this is due to most short chambers actually being longer than nominal length — I’ve found very few as short as 2.5″ — and partly because most 2.75″ shells are slightly shorter. A lot of shooters buy or handload shorter ammo, or lengthen the chamber slightly, but if the gun’s in good shape, many use 2.75″ ammo with no problems.

Some tool-free tests should be performed on older doubles. First, check the position of the opening lever. When the gun’s closed, it should be to the right of center. If it’s centered or to the left, the action’s probably loose.

To check for looseness, remove the fore-end then hold the shotgun by the grip with the barrels hanging down and shake it vigorously. If it rattles, the action is loose. This doesn’t necessarily make a shotgun dangerous to fire, but usually looseness grows worse. Most loose doubles can be tightened but the price should be adjusted for the cost. (One of my drillings is a century-old SAUER tightened by the well-known Houston firm, Briley Manufacturing. Aside from making and installing their excellent choke-tubes, Briley also does just about any kind of gunsmithing.)

The second test involves removing the barrels from the action, then while holding the barrels very lightly, tap them with a penny. If the solder’s solid, they’ll ring like a gong. If the solder between the barrels is loose, the sound will be duller, and sometimes include a slight buzz. This also isn’t dangerous, but will only get worse — and can be fixed.

Some rifle models tend to be more valuable when older (above), even when they have a little exterior wear. This Marlin Model 39 .22 is a good example. If you buy used shotguns, one handy tool is a chamber-length gauge like the Galazan (below). The tapered leaf on the right provides a rough idea of choke.

Some people may claim there are problems with a gun you’re selling. At the same show where the guy ranted about my 8×57’s scope-mount holes, I also had a nice Flues model Ithaca side-by-side 12-gauge for sale. A notorious sleazeball came by and asked permission to do the standard exam. I said OK, just to watch him in action.

I’d brought a pair of plastic snap-caps for anybody who wanted to test the Ithaca’s fine trigger pulls. He tried them and nodded in approval, then took off the fore-end and tried to rattle the gun, but the action proved tight.

Finally he took off the barrels and removed one of the snap-caps, “ringing” the barrels with its rim. Since the snap-cap was plastic, the barrels naturally went bonk instead of bong, and rattled due to the snap-cap in the other chamber. He told me the barrel solder was bad, and asked if I’d sell the gun for $250 under my asking price. Not! (Semi-sophisticated shotgunners often claim the actions of Flues Ithacas can crack when shot with modern ammo, but that’s only true of 20-gauges, because they have the same size cuts in a smaller frame. I’ve yet to see a cracked 12-gauge Flues.)

Aside from unseen modifications, problems with guns made since World War II aren’t common, and almost unknown among rifles with synthetic stocks and stainless-steel actions and barrels. The most common problem I’ve seen is poorly home-done epoxy “bedding,” easily discovered by removing the stock and usually easily fixed.

However, I’ve owned two .350 Remington Magnums, one a Remington 700 and one a Ruger 77 Mark II. The Remington fed rounds perfectly, but it took half a day in my shop to get the Ruger to work right. This isn’t uncommon with controlled-feed actions chambered for short, fat cartridges — one reason I’m dubious about the present mania for controlled-feed actions among some shooters.

If you show a little caution, used rifles and shotguns can be very good deals, because like used pickups, somebody else paid for the factory profit margin. Used custom guns, in fact, can often be picked up for little more than the cost of the parts used when putting them together. This is why many of us constantly stalk sporting goods stores, pawn shops and gun shows. This takes time, but it’s fun time, unlike the Friday after Thanksgiving.

For More Info:

Blue Book Publications, Inc.

8009 34th Avenue South, Suite 250

Minneapolis, MN 55425

(800) 877-4867