Gun Notches

Counting Coup In The Old West

The stubble-faced, black-hat-wearing outlaw sneered as he carved another notch in his Colt. When completed, he rubbed his thumb over it and sniggered. It was his medal, a monument to another victory; at least, we see it in the movies. But did Hollywood get it right? Maybe.

Did they?

Some claim carving notches on a gun never really occurred in the Wild West. Some argue gun notches were added over the last 100 years to sucker in gullible buyers. However, others point to well-documented notched guns on display in museums as iron-clad proof. So, what is the truth? I found documentation between the Civil War and WWI proving it did exist. In some ways, it still exists.

Some feel notching a gun represents a life lost and is demeaning. I understand the sentiment, but to many, it is a celebration of surviving and being the victor of a dangerous feat. It is a visual reminder of a struggle against the odds. I’m sure if we were to dig enough, we would find notches, metaphorically or literally, in some form back to the Stone Age.

We don’t have the space to go so far back, so I stopped at the 1800s Plains Indians. Most tribes had warrior societies that glorified combat. The ultimate feat was to touch an enemy in battle and count coup. Counting a coup on a live and healthy opponent up close was much more dangerous than sticking an arrow or bullet in one from afar — the ultimate test of bravery! Face-to-face, mano-a-mano. If death was the result, scalping was another form of counting coup.

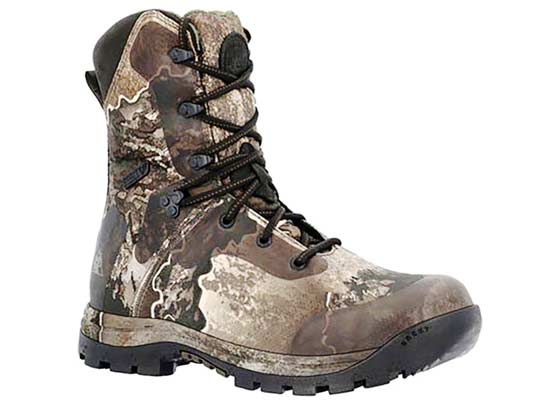

According to Lowell’s family history, Buffalo Bill Cody once owned this

Ainsworth-inspected Colt SAA. Seven notches are carved in the grips.

According to documentation, it is believed this SAA was not only owned by

Buffalo Bill, but it likely fell into Indian hands at some point. Note the star

carving and inspector initials. It also looks somebody used it as a hammer,

which wasn’t uncommon! Photos: Todd Bachli

Historical Record

The earliest documentation of “notching” a firearm I found was from the Civil War. In the book Jack Hinson’s One-Man War, the author pieced together the life of Kentucky farmer Jack Hinson. Tragic events led to the wrongful execution of two of his sons by a Union officer. Even worse, the officer had the boys’ heads placed on pikes to warn any Confederate sympathizers. Grief turned a peaceful farmer into a deadly sniper.

Hinson knew a location on the nearby Cumberland River where the banks swung close. The result was a swift-running chute that slowed the Union troop transports and supply ships heading upriver to a snail’s pace. Hinson had a long-range rifle built and commenced exacting revenge on the Union Army. From the bluffs high above the river, Hinson picked off the gold-wearing officers on deck. For each officer Hinson killed, he punched a mark on the barrel of his rifle. By the time the war was over, the gun had 36 marks. Hinson said he only counted officers and the actual tally was over a hundred.

The term “notch” was also used metaphorically. Tom Rynning, Captain of the Arizona Rangers, told of life in the border town of Douglas in 1902. “The dance halls were the worst I’ve ever seen on any frontier. Most of them were run by men who’d plenty of notches on their guns….” A few pages later, Rynning told of a plot to kill one of his rangers by saloon owner Walker Bush, a badman with at least seven notches on the handle of his .45.

The custom of cutting notches led to slang. A “notcher” was a man who went looking for a reputation and a horse with a notch-in-his-tail had killed someone.

In 1881 a story ran across the nation about the “Texas Notchers” who terrorized the Silver City region of New Mexico. “Their name arose from the fact they kept a tally of the men they killed by cutting a notch from each one on the stock of their arms.”

In 1890 a story ran in the Omaha Bee about the discovery of weathered human remains along with a rusted Colt revolver with 29 notches filed on the barrel. Old-timers remembered the decades-old story of William Stebbins, known as Catamount Bill. A hungry Catamount Bill stumbled into a hunting camp. During the visit, Catamount displayed his revolver with seven notches filed on the barrel. A few weeks later, he returned with five new notches on his gun. It was then he admitted he had killed a Sioux brave for each notch.

In the weeks following, Catamount would work with the trappers, then disappear. He was seen again in the fall, claiming he had killed a Sioux warrior every week he was gone. But Catamount was feeling ill and heading back downriver. When the revolver and remains were found, they realized Catamount Bill had never made it home. Did he die of illness or did a Sioux warrior cut a notch of his own?

“Enhancing” History

In 1891, a story ran in Kansas stating Billy the Kid’s famous gun would be on display at the World’s Fair, but the 21 notches carved into the stock were cut by the present owner to represent the number of the weapon’s victims. At least the owner was honest, but it is interesting they had already started blaming the gun, not the person using it.

In May 1894, the last of the Dalton Gang went out in a blaze of gunfire in Guthrie, Okla. Once the smoke cleared, they found the Winchester rifle used by Bitter Creek Newcomb. The stock had a series of notches counting the men killed by the outlaw.

In 1895 a young man informed the local sheriff a man incarcerated in Garfield County had killed two men and notched the trigger guard of his revolver. They checked and two notches were found. In the same year, Kentucky outlaw Rush Morgan was slain. His Winchester rifle had 17 notches carved in the stock for the men he killed.

Even the young George Patton notched his Colt SAA after killing some of Pancho Villa’s men in combat.

In 1907 Buffalo Bill Cody gifted his battered Colt revolver to neighbor Calvin Lowell, Deputy Sheriff of Lincoln County, Neb. The revolver appears to be an overrun, inspected for the military but never delivered. When Cody was to have purchased the Colt, he was alternating between acting in western plays and scouting on the plains. What the seven notches on the grips indicate makes one’s imagination go wild.

Bad Reputation

While notching was practiced, the stigma attached to it was often negative. Wyatt Earp said, “I never knew a man who amounted to anything notch his guns…. Hickok, Bill Tilghman, Pat Sughrue, Bat Masterson, Charlie Bassett, and others of the like caliber — have handled their weapons many times but never knew one of them to carry a notched gun.” But Earp did relate a story about his friend, Bat Masterson.

Masterson was working in New York City as a sports writer when a collector bugged him to no end for one of his guns. Finally, Masterson bought an old Colt .45 at a pawn shop. Masterson decided to give the collector a thrill and carved 22 notches in it. When the collector returned, Masterson passed off the old Colt as his own. Word got around and not long after, the dime novels upped Masterson’s kill count to 22!

Thousands of examples can be found by researching old newspapers and journals of the period. Even if we discount the majority as being exaggerated, it still leaves countless examples that can’t be ignored.

Undoubtedly, notches were added to other “Old West” artifacts over the last 100 years, and unless they are well documented, each has to be inspected with a cynical eye.

Notching extends to hunting rifles. Thomas R. Taylor (USA/USMC) told me about an old sheepherder’s Winchester ’94 he had seen. “He had cut notches on the bottom of the butt stock for deer, on the bottom of the forearm for elk, on top of the butt stock just ahead of the butt plate for pronghorn, and a few on the right side of the butt for a pair of cougars, a bear and a half dozen or so bobcats. He never counted coyotes because he said they didn’t matter, and there wasn’t a stock made big enough for the number he’d killed.”

Many examples show the practice of notching continued through the various wars and conflicts of the 20th Century. Soldiers sometimes notch their guns to count a battle they survived, a successful campaign and even individual kills. During the Spanish-American War, soldier Warren Bowen wrote he and his outfit had lost track of how many notches they were entitled to carve on their rifles.

One tradition related to notching continues to this day. Look at many fighter planes and you’ll most likely find mission victory insignia. They are a form of notching, even if no actual notches are carved.

Do notches increase the value of a gun? Most collectors will say no. The motto is to “Buy the gun, not the story.” But, for me, it does make the imagination run wild.