A Six-Shooter For TV Cowboys

With TV Western's Booming, Great Western Produced

A Reasonable Facsimile Of Old Colts To Meet Demands

Of Drug Store Cowboy Guns

This article was reproduced from GUNS Magazine May 1955.

They Say that on a cold night, when you walk past the stern figure of Samuel Colt standing as a monument on his grave in Hartford, Conn., there can be seen a faint smile on his cold marble lips. And many people wonder why he is smiling. Maybe it is because some 3,000 miles away, in the City of the Angels in the land of California, there is a man who is doing the same thing Colt did back more than a century ago. On borrowed capital and a determination to make a good product, William Wilson of the Great Western Arms Company is building a new version of Colt’s famous “Peacemaker.”

Wilson’s shop in Los Angeles is a small plant employing a couple of dozen mechanics. The walls are tin sheeting, the machine layout inefficient, the production small. But there is Colt’s “spirit of 1847” here, recalling the time when Sam Colt, with $14,000 in his pocket and some used machines, set up shop for the first time on Grove Street in Hartford. Colt’s first works was small but by working 20 hours a day, by gathering about him men of specialized talents in many fields, he built a factory, fortune, and a legend . . . the legend of the “Colt.”

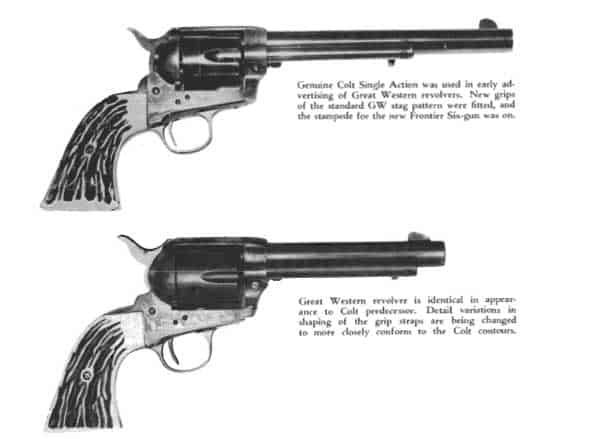

That legend is dramatized today in the hundreds of movies and television stories about the wild west of the last century, where trails were blazed in gunsmoke through desolate Indian country. The one gun most used in these films is the venerable Colt Single Action or “Peacemaker.” Such publicity has been, for the Colt company, ill-timed. This gun is no longer made by Colt. However because of its TV popularity a demand for the weapon has arisen among gun enthusiasts all out of proportion to the number of existing genuine Single Actions. Watching Roy Rogers and Wild Bill Hickok shooting it out with badmen on TV screens, a new species of drugstore cowboy came into being; all seemed to want to own a Single Action sixshooter. With Colt defaulting on this demand, a West Coast businessman decided to do something about it. William R. Wilson couldn’t duplicate the old Colt, but he decided he could make a reasonable facsimile to satisfy the new “cowboys.”

Wilson formed the Great Western Arms Company, an independent corporation with no connection to any other firm. He has been pretty particular about making this point, because some people wondered if he “was connected with Colt.” Others consistently referred to his gun by the name of Hy Hunter, a principal distributor.

For the initia1 tooling, about $180,000 was sunk by Wilson into his plant. Costs of manufacturing have risen indeed since Sam Colt went into business!

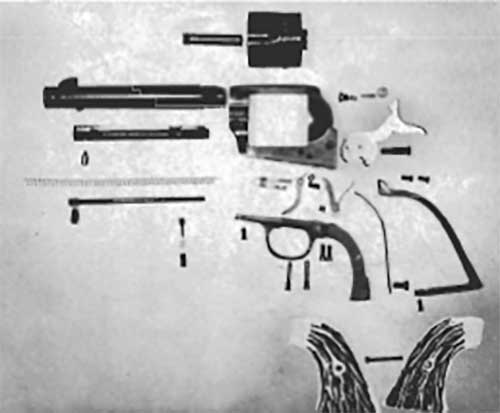

Wilson’s idea was to offer a gun exactly like the “Colt,” with several small but important improvements. Trigger and bolt screws in the GW “Frontier” are of a different thread from the original; they stay put more securely under the shock of firing and do not shake loose. Instead of making a forging for the frame, he uses an invested chrome-molybdenum casting of aircraft quality steel. The straps, trigger guard and hammer are all of chrome-moly, while the cylinders are of high-carbon S.A.E. 4140 chromemoly treated to 36 Rockwell on the “C” scale. This alloy steel is much more difficult to machine easily but results in cylinders of great strength. Pressures of 52,000 p.s.i. have been fired in GWs .357 Atomic with no difficulty, while handloads of 30 grains of Hercules 2400 have failed to do any damage in the .45’s. However 27 grains bulged a comparable Colt cylinder. The trigger and cylinder bolt are coined from beryllium bronze alloy, a metal well adapted to spring purposes.

Wilson’s new Frontier is made in .22, .38 Special, .44 Special, .45 Colt, and a new caliber, the .357 “Atomic.” This last is an extension of the earlier .357 Smith & Wesson loading, squeezing a little more powder into the case, and boosting the muzzle velocity as gauged by Roy Weatherby’s Potter Counter Chronograph to 1660 feet per second, giving 906 pounds muzzle energy. The bullet is somewhat lighter khan the regular .357 Magnum loading, 148 grains against 158, which in part would account for the higher velocity. Actual velocities of the .357 Magnum cartridge do not stack up well compared to the catalog figures of 1450 f.p.s. in an 8 3/8″ barrel, being somewhat less.

In the absence of any proof to the contrary, Wilson’s boast of “the most powerful handgun ever made” stands for the .357 Atomic GW Frontier. Regular .38 Special and .357 ammunition may be fired in the Atomic, but Atomic ammo is too long to chamber even in the .357 Magnum revolvers of other makes. The Frontier has been planned in .30 US. Carbine caliber, but so far none have been produced.

The new “Frontier” has had a tough row to hoe. Gun fans wanted it exactly like the old Single Action, which Colt said they would not produce again. That was where the trouble began. The Colt was made and finished by workmen who knew their jobs. Men were at the Colt benches who had been on their jobs for 60 years. Some tools used to make the Colt dated from the Civil War!

A heritage of gold-dollar craftsmanship in a cutthroat depression made the Single Action one of the finest guns ever made. And it was all accomplished through extensive hand fitting nearly 100 years of manufacture of the same or similar item. This no company today could hope to equal, and the early Great Western show it.

Two .45 caliber GW’s in the GUNS Magazine collection, numbered below #200, show very poor fitting and an ordinary buff-the-‘ell-out-of-it bluing job. The first two guns of the Frontier ever made had Colt hammers in them; these, also, seem to have scrap Colt hammers with the notches welded up and poorly re-cut. Triggers pulls are bad, and the fired cases stuck in the chambers, showing scratch marks alter finally punching them out.

Gun #640 proved to be very accurate blipping jack rabbits from a car until the first misfire. While the bunny hopped away, I clicked the gun ten times, with no effect. The cylinder bushing advanced so much from the shock of firing that the primers were not hit by the pin. All after only 15 shots! With a pair of pliers I squeezed the bushing enough to burr it and set the cylinder back to proper headspace distance. There was no subsequent trouble, until the heavy hammer spring snapped off the sear end of the trigger. At about this rime, only a few hundred shots from “new,” the cylinder bolt limb also broke, freezing the gun. New parts were obtained and installed. The sear broke again. The gun was shipped back for a refund.

In an attempt to get a really good gun, another one was ordered. This was also .45 caliber. The frame inside had a bump which scarred the cylinder blueing, while the cylinder bevel at the front edge actually cut into one of the chambers. This gun, too, was sent back.

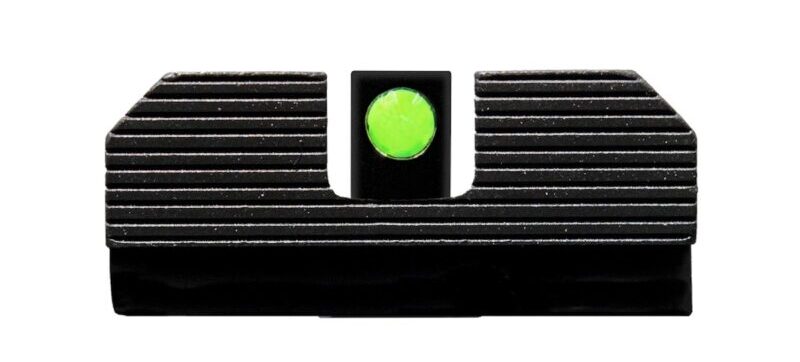

Having shot up all my .45 ammunition, I next ordered a 22, serial #2064, with the popular 5 1/2″ barrel length and case-hardened frame. A distinct improvement was noticed in this gun, so far as finish went. The grip straps and frame had been polished assembled, which makes for proper frame contours where the grips tie one. The front sight was not simply a plate of sheet metal stuck on to look pretty, but was actually filed down and shaped to allow good shooting at 20 yards with .22LR ammo.

The ejection of fired cases was easy, and by rolling the cylinder past the click and then backing it up a trifle against the pawl, the chambers lined up to permit the ejector rod to enter and push out empties. This little trick, once made a habit, speeds up the operation of this type of gun.

Trigger pull was heavy-probably seven or eight pounds. But it was pretty regular and with a good let-off. Finish on barrel and cylinder was good-the polish of these two parts has always been pretty clean and ‘crisp.” The bad part continued to be the grip straps themselves. They were not forged with the same roundness of original Colt straps-thus the grips appear sloppy in fitting and “effect!”

After the first solid firing pin Colt hammers had been used up in Great Western frames, an improved floating firing pin made by the Christy Gun Works was used. This meant that the hammer had to be notched like the popular Christy SAA modifications. In my .22, the pin bushing became burred from poor fitting of the hammer, and the firing pin blow became weakened, resulting in misfires. The bushing was easily removed by a split screwdriver; a file stroke or two knocked off the burrs and cleaned up the hammer. Several hundred shots were then fired, fanning and aimed shooting, without trouble, and with a lot of fun.

Wilson now makes his own floating firing pin fitted to GW’s above #3100, of essentially the same design but to dimensions which now prevent it from shaking loose. Grip straps also have been improved above serial #3000. New dies give the rounded appearance of the original Colt, instead of the “flat” look. This oddly parallels Sam Colt’s own designs of a century ago: the Walker and early Dragoon revolvers had a “flat” appearance to the backstrap, while the later No. 2 and No. 3 Model Dragoons showed a rounded improvement.

Since the GW is a rod ejector gun, BB Caps can be used and at 22 feet indoors you can make them touch on the target-if you’re steady. Offered in 5 1/2″ length only, the .22 being the lowest priced of the series will make it probably the most popular. It goes “bang,” yet can be used almost anywhere. But if you’ve got to play “Wild Bill” in your garage, shoot into a big sandbag and. away from any houses or people . . . better yet, wait till you can get out into the country to play “cowboy.”

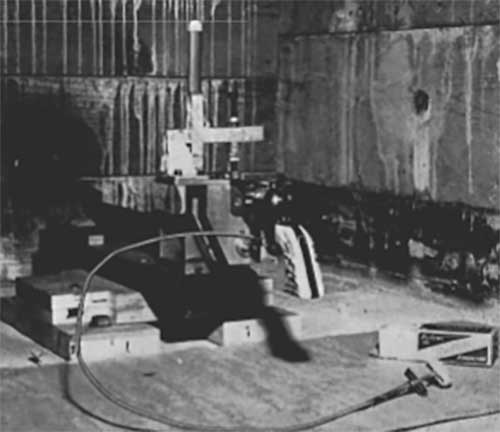

There have been several stumbling blocks in the production of the new Frontier. Beryllium alloys proved superior than steels in tests. But the gunsmiths and buying public didn’t know that, and complaints were loud. Echoed, there seemed to be more to the defect than really was present. Electric motors running links to cock and fire guns were used by Wilson in fatigue testing. He states that “steel parts after 5,000 movements of the action were badly worn, the trigger showing considerably more wear than the beryllium copper. The bolt broke on several occasions before the full 5,000 movements were complete. Under ordinary usage we have found by tests that after 5,000 movements of the action our beryllium-hand, bolt and trigger are all in reasonably good shape. There have been broken triggers, but we have also broken quite a number of Colt triggers trying them in our guns.”

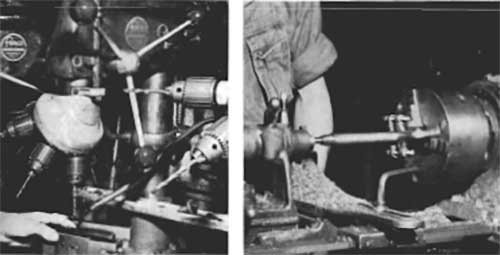

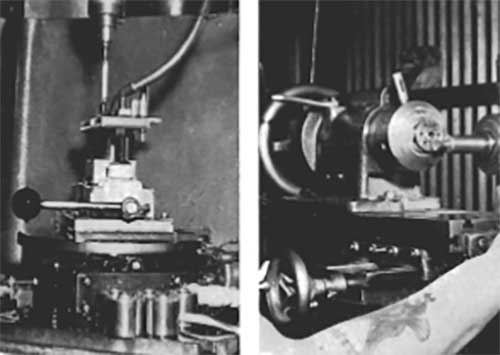

Manufacturing methods have also improved. Barrel blanks are bought from Roy Weatherby ready for outside finishing. Weatherby’s experience in making high velocity rifle barrels accounts for the fine quality of the GW barrels, even though to give that extra look of quality, GW barrels are individually lapped with lead slugs and polishing compound.

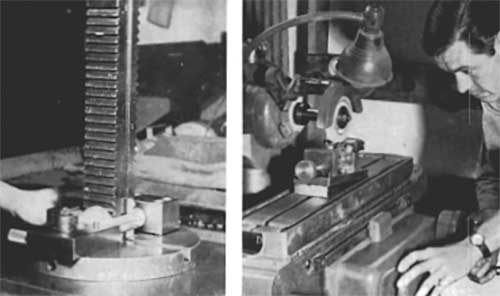

L. E. Linder, a highly competent engineer who is learning more about guns every day, has been responsible for many subtle improvements which show up in a better product. Frames had been left almost as they came from the moulds, except for polishing and case-hardening, but Linder and Wilson have finally installed an expensive vertical broaching machine to end cylinder fitting difficulties. The broach is dragged through the cylinder hole and shaves the frame inside edges clean and true.

The GW guns have an appearance of having “never been fired” as they come from the box. This is not true. Every gun is test fired at a target with proof and regular loads, from a two-handed rest position. The target is shipped with the gun. But, the cylinders are not blued. Since each part bears the gun number, it is easy to route the cylinders, after cleaning, into the blueing tanks where a hotnitrate process colors them. Then they are returned to the finished guns and wrapped for shipping.

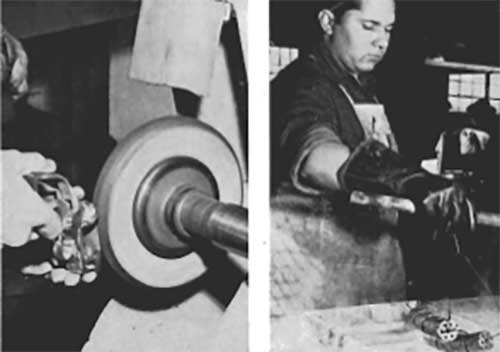

Polishing and blueing are two of the most important of all operations. The finish of any product is important, but the finish on a GW Frontier is especially critical. Inevitably the customer will compare it with the peacetime, depression, solid-gold-dollar-built Colt. At first, the barrels and cylinders were spun well and buffed nicely, but the frames looked terrible. A glossy polish was used, resulting in a gun which had all the appearance of being a genuine Colt after leaving the hands of some butcher rebluer. Polishing was in the wrong direction on grip straps and the whole appearance was bad.

A steady improvement was noticed. The first step was polishing the frame and straps in an assembled condition, then stripping for further work. This meant that the edges where they met were sharp, not rounded and ugly. All the frames are hardened in a molten cyanide salt bath, which carburizes the surface without embrittling the tough chrome-moly interior of the steel. Since they are polished they take the delicate mottled colors, so prized by Single Action fans, when quenched in water which has air bubbling through it. Following the old Colt style of finish, the combination of blued parts and colored frame makes a very pleasing appearance.

Final inspection and assembly go hand in hand, and the men had to learn from scratch. As a result, many of the guns are fitted so that undue stress is focused on the cylinder pawl and on the bolt, which makes these parts fail. A groove fillet between the spring leaves of the bolts would prevent fatigue failures here. Filing the backstrap to act as a hammer stop, and then fitting the other parts to time exactly right would be a significant improvement. Wilson is aware of all these things. Recently he obtained a copy of Ordnance Memorandum No. 22 which gives full details of the inspection during the 1870’s of the Single Action Army revolver. His own new Frontiers should continue to show improvement.

Wilson is something of an enigma as a person. Quiet and soft-spoken, he is the antithesis of the usual flambouvant California character. Yet with a quiet determination he has pitched in and brought the Single Action to life in his new Frontier. Although Wilson has a private backer, gun entrepreneur Hy Hunter was also of help and encouragement during the early days of the Great Western company. Hunter’s own sales firm, American Weapons Corp., is a distributor of the Great Western and Hy has been more than anxious about production, quality, and getting guns out to the market. Gradually gaining momentum, though limiting production to about 250 guns per week, Great Western has been building up an enviable backlog of orders. The temptation to overproduce and have a large amount of money tied up in machines has been resisted. Frontiers are run through the shop in batches, and all frames are numbered consecutively from “1.”

Even Colt’s is glad to have someone else making these guns, relieving them of the questions which collectors and Single Action fans have raised. Frequently, when Wilson’s own suppliers have been short and he needed small parts in a hurry, Colt’s has been glad to help him out.

For all the scoffing which has been done about the basic Single Action design, one fact remains above all others. This gun, whether made by Colt or Great Western or others, has “oomph!” Not easily defined, you can only say that the gun looks like a gun, handles and hangs like a gun . . . .

Great Western is not content to rest on the curio market which Wilson has captured with the Frontier. A new edition of Frontier lock work is in the offing. Redesign of small parts will eliminate the minor breakages inherent in the Frontier design. The grip of the Frontier, which has been many times copied but never surpassed, will soon appear on a double action, modern service version of the old design.

This article was reproduced from GUNS Magazine May 1955.

Get More Revolver Content Every Week!

Sign up for the Wheelgun Wednesday newsletter here: