.455 Webley-Fosberg

Shades Of The Maltese Falcon, This Auto-Revolver Delivers One Of History’s Mysteries

Oct 30, 1863: The Umbeyla Campaign in northwest India, part of the effort to secure the frontiers of the British empire. A remote mountain outpost called Crag Picquet has been overrun, 60 of its defenders killed in hand-to-hand combat.

British and Indian troops climb the rocky terrain in an attempt to retake the outpost, and Lt. Col. Keyes leads one column of troops. Huge boulders force the men to proceed in single file, making them easy targets for enemy fire. Keyes directs Lt. Fosbery of the 4th Bengal European regiment to lead a small party of soldiers along a different line of attack. Keyes later reported, “He [Lt. Fosbery] led this party with great coolness and intrepidity and was the first man to gain the top of the Crag on his side of the attack.”

Keyes was wounded after leading his troops to the top. Lieutenant Fosbery then took command of the remaining troops, organizing and leading a pursuit of the enemy, inflicting further casualties and consolidating the victory. For his actions, Lt. Fosbery earned the highest award for gallantry in the British Commonwealth, the Victoria Cross. His commendation reads in part, “For the daring and gallant manner in which … he led a party of his regiment to recapture the Crag Picquet.”

In the 150 years of its existence the VC has been awarded just 1,354 times. Lieutenant. Fosbery was 30 years old at the time of the action at Crag Picquet. He served in the British Army for another 14 years, earning several promotions. In 1877, Lt. Col. George Vincent Fosbery, VC, retired from active service and began pursuing his interest in firearms.

Paradoxical

One of his developments was the “Paradox,” a shotgun with a short section of rifling near the muzzle. As the turn of the century approached the first self-loading handguns began to appear. Fosbery turned his inventive mind towards a design combining the virtues of revolver and autopistol. His first prototype was built on a Colt Single Action Army revolver, with the cylinder, barrel and top half of the frame sliding on the remaining part of the frame. On Aug. 16, 1895 he was granted a patent on his design, with additional patents added in June and October of 1896.

To develop his concept, Fosbery turned to England’s foremost revolver manufacturer. In 1835 Philip Webley and his brother James founded a gunmaking firm at Birmingham. James died in 1856. Philip kept the company going, joined by his sons Thomas and Henry during the 1860s. Philip Webley had been most impressed by the manufacturing genius of Samuel Colt, and his concept of assembling revolvers from interchangeable parts. When Colt closed his London factory in 1857, it left the field open for Webley to follow Colt’s lead. Several successes followed; the adoption of a compact Webley by the Royal Irish Constabulary; the hinged-frame revolver design in 1870; and the big breakthrough, a contract with the British War Office in 1887.

Philip died the following year but his sons kept the company going. In 1897 it merged with Richard Ellis & Sons and W.C. Scott & Sons to form the Webley & Scott Revolver & Arms Co. Webley’s dominant position in the revolver market, its reputation for quality, and its association with the military made it a logical partner for a soldier and firearms enthusiast such as Fosbery.

The Auto Revolver

The Webley-Fosbery automatic revolver was demonstrated at the Bisley matches of July 1900. In July, 1901, a British sporting magazine, The Country Gentleman, reported approvingly “The six cartridges carried by the Webley-Fosbery can be discharged with good aim in six seconds.” One of the foremost British target shooters of the time was American-born Walter Winans. The Webley-Fosbery became his arm of choice. At a demonstration in 1902, Winans fired six shots into a 2″ group from twelve paces in under seven seconds. Using an early speedloading device he fired twelve shots into a 3″ group in fifteen seconds. Neither performance would cause current IPSC champions to lose much sleep, but for the era this was big news.

Lieutenant Colonel Fosbery, perhaps not the most unbiased judge, reportedly said: “It is the most formidable weapon in existence for close combat or personal protection, and among service revolvers cannot be beaten by any similar weapon in England or America.” Despite good press and endorsements, by any objective standard the Webley-Fosbery would have to be considered a failure. Its design proved to be an evolutionary dead end. It inspired no imitators, set no trends and wasn’t adopted by any military. Excellent workmanship aside, it’s rather a homely, ungainly looking beast. It remained in production for less than two decades, with only about 4,750 being manufactured.

Yet it remains one of the most fascinating handguns ever made. Webley-Fosbery serial number 1991, pictured here, is in the collection of my shooting buddy, Steve Kukowski. Kukowski, a police detective and top competitive shooter, is also a highly knowledgeable collector. The Webley-Fosbery is a gun he hardly dares display at gun shows anymore. Not only does the resulting traffic jam block the aisle, he has to spend the evening removing the fingerprints and drool. One old-timer visits Kukowksi’s house a couple of times a year just to look at the Fosbery. There’s something about it that appeals to even them most jaded handgun enthusiast.

How’s It Work?

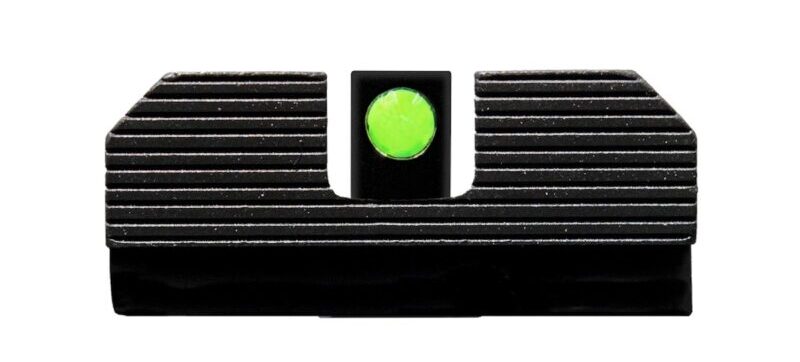

The Webley-Fosbery consists of three main components. The two-piece upper assembly includes the barrel/cylinder assembly and locking latch/hammer assembly. Locked together in closed position, they form a single unit which slides back and forth on the lower assembly. The lower assembly includes the grip and trigger components. The cylinder is grooved in a zigzag pattern and the grooves engage a fixed stud in the lower assembly. On firing, recoil drives the upper unit to the rear; and the zigzag grooves, following the fixed stud, rotate the cylinder 30 degrees. At the same time the frame pushes hammer back to the cocked position.

A spring then pushes the upper unit back into battery. As the assembly moves forward the cylinder rotates another 30 degrees, bringing a fresh cartridge in line with the barrel. Cylinder rotation from the shooter’s perspective is clockwise. An obvious concern is to make sure the cylinder rotates in the proper direction on the forward movement of the assembly, rather than simply turning back to bring the fired cartridge under the hammer.

The designers actually figured out not one, but two methods. The 1901 model used a spring-loaded stud in the frame and cylinder grooves were cut to different depths. The grooves engaging the stud during rearward movement were shallower than those engaging the stud during forward movement. As the upper unit reached full rearward position, the spring-loaded stud would extend into the deeper groove and keep the cylinder rotating in the correct direction. Though the system proved reliable, it was expensive to make and needlessly complicated.

The 1902 model used a fixed frame stud and grooves of uniform depth. The grooves are slightly offset so as the upper assembly moves forward, the cylinder is forced to engage the correct groove with the stud. The 1904 model has a shorter cylinder and some minor modifications to the lockwork for greater strength and durability. The majority of Webley-Fosberys, including the one pictured here, are 1904 models.

A few Fosberys were made in .38 caliber with eight-shot cylinders. Grooves on these cylinders had a slightly different geometry since rotation for each shot was 45 rather than 60 degrees. The majority of Fosberys were chambered for the .455 British service cartridge. Original .455 Mk. I cartridges were chambered for black powder. Smokeless powder provided similar ballistics with a smaller charge, so the case was shortened to form the .455 Mk. II. Fosberys were typically marked “.455 Cordite,” indicating they were to be used with the smokeless Mk. II load.

Making It Go

Loading the Fosbery is similar to loading any top-break Webley. For a right-hander, it’s best to hold the barrel horizontal with the left hand. The right hand depresses the locking latch, then lowers the grip frame. This activates the spring-loaded extractor which kicks fired cases clear, then snaps back flush with the cylinder. After loading fresh cartridges — either singly or with a speed-loading device — the grip is raised until the locking latch clicks shut. With a regular Webley, the handgun would now be ready for action. The Webley-Fosbery, remember, is an automatic. Neither hammer nor trigger has any effect on cylinder rotation.

To ready the Fosbery for shooting, the shooter grips the knurled sides of the hammer and pulls straight back, drawing the upper assembly to its full rearward position, and releases the hammer to let the assembly move forward again. This cocks the hammer and serves as a check that the cylinder grooves are properly engaged with the frame stud, indexing a cartridge with the barrel. The large manual safety on the left side of the grip frame is then pushed up, exposing the word “SAFE” on the left grip panel. Engaging the safety moves the upper assembly back slightly, disengaging the hammer from the sear. Pressing the safety down makes the gun ready to fire.

Some references state the safety is moved down for on, up to fire. I’ve also seen references stating the safety cannot be applied unless the hammer is cocked. Either s/n 1991 is different from all the rest, or else those authors never actually handled a Fosbery. The safety lever can indeed be pushed up to “safe” position with the hammer uncocked. Doing so moves the hammer back just far enough so the firing pin does not rest on a primer.

With a standard revolver, cocking the hammer, or pulling the trigger on a double-action model, rotates the cylinder and brings up a fresh cartridge. In an era when ammunition was by no means as reliable as at present this was considered an important advantage. With the Webley-Fosbery, critics pointed out, a dud round could leave the shooter futilely pulling the trigger or cocking and snapping the hammer repeatedly on the same bad cartridge. Fosbery contended this was no different from any other automatic pistol. The proper corrective procedure with a dud round in an autoloader is to hand-cycle the action to bring up a fresh cartridge. In practice, grabbing the checkered sides of the hammer, yanking back and letting go brings a fresh round into play about as quick as hand-cycling the slide of a 1911.

Just Plain Cool

The Webley-Fosbery was never a military issue weapon. British army officers typically purchased their own sidearm up to about 1916 the only requirement that it be capable of accepting the .455 Mk. II service load. Webley-Fosberys were no doubt carried into combat in the war, though considering the small number produced their use could not have been widespread. One reason may have been their susceptibility to mud and dirt. Actually all handguns, especially revolvers, have a tough time coping with mud. A more likely factor was cost, and Fosberys were not cheap to produce. Most officers of the era probably felt a standard model cost less and would serve just as well.

Production of Webley-Fosberys ended in 1918, though the model remained in Webley catalogues until 1939. In America it is best known, not for its feats on the target range or in battle, but for its appearances in popular entertainment. A .38 caliber Webley-Fosbery was integral to the plot of Dashiell Hammett’s novel The Maltese Falcon, and in the 1941 movie of the same name. In the novel, private detective Sam Spade, says “Yes. Webley-Fosbery automatic revolver. Thirty-eight, eight shot. They don’t make them any more.” Another Webley-Fosbery is wielded by the character Zed, played by Sean Connery in the 1973 movie Zardoz.

The Fosbery from Kukowsk’s collection is one of the best examples still in existence, mechanically perfect and with only minor blue wear. “They don’t make them like they used to” is a cliché, but like many it also happens to be true. In some ways they may make them better, with stronger steel, more efficient design, but they don’t make them the same way.

Parts fit is excellent, flats are truly flat, and there’s a polish and finish that is seen today only on custom guns. I was sorely tempted to shoot it, and Kukowski didn’t help when he said to go ahead if I wanted. We have an agreement whereby he can shoot any of my guns, and vice versa, with two unwritten rules: you shoot it, you clean it, you break it, you bought it. The ammunition available was old, with corrosive primers. The temptation to be one of the few handgunners to actually shoot a Fosbery was strong, but was tempered by the thought of damaging an artifact worth several thousand dollars. The excellent condition of s/n 1991 was the deciding factor. I just couldn’t bring myself to risk it.

Kukowski had another .455, a Webley-Greener Army model through which I popped a few rounds. Ammunition in .455 Mk. II was offered as a target load, with 265-grain lead bullets, and a military load with jacketed bullet. Rated at 600 fps, the lead bullet loads chronographed at 535 fps. from the Army model’s 6″ barrel. Not exactly lion medicine, and the conical profile and metal jacket of the military load hardly enhance performance. You’d go some to make a more inefficient design. Still, a big, heavy bullet is not to be disdained, even at airgun velocities.

Lieutenant Col. Fosbery died in 1907. The Empire for which he risked his life is gone. Webley revolver production ended in 1983 when all remaining tools, dies, fixtures and blueprints were sold to an engineering firm in Pakistan. Of the fewer than 5,000 Webley-Fosbery revolvers made, some no doubt were lost in the trenches of the first World War, along with the men who carried them in defense of their country. Others came back and become cherished family heirlooms, only to be confiscated and destroyed by the government of the same nation they had once defended.

Those which survive deserve better than to be associated with dime-novel detectives or movie fantasy. Better we should remember a courageous young military officer leading his men to battle and victory.

Get More Revolver Content Every Week!

Sign up for the Wheelgun Wednesday newsletter here: