Optical Delusions

When shooting, are your eyes playing tricks on you? Sometimes …

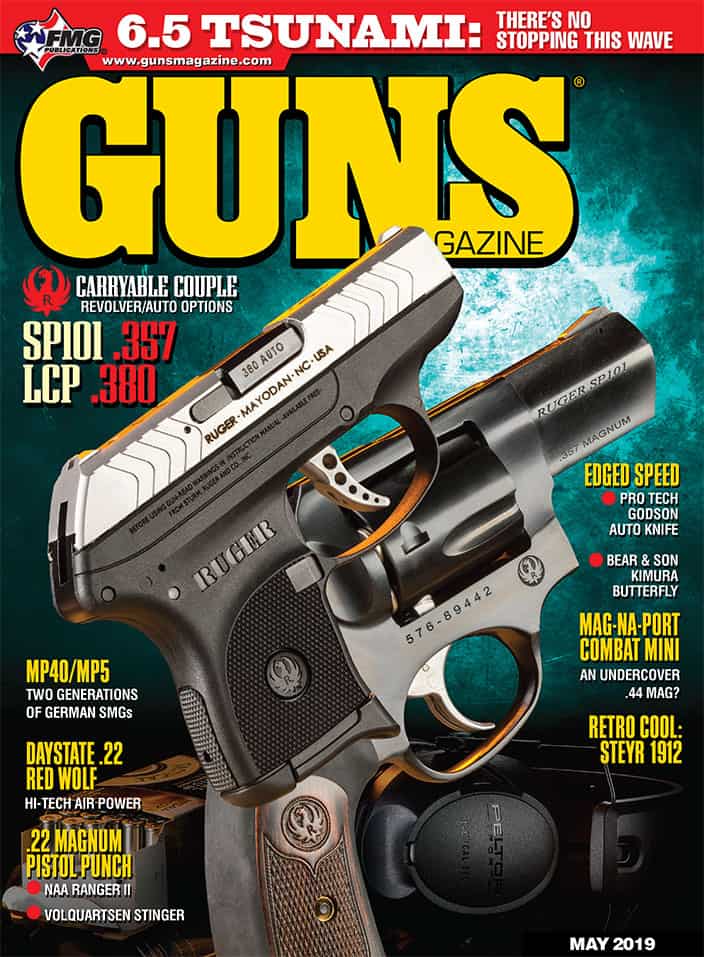

Mas was behind this S&W M629 .44 Magnum when he misjudged the shooting distance by 20 yards. He thinks it was due to tunnel vision.

Somewhere between target and brain are your eyes and front sight. It’s pretty straightforward but sometimes along this line, things get misinterpreted because of two well-known optical phenomena. We’ll talk about them and how they can really foul up your handgun shooting.

Follow The Light

If you’ve shot with metallic sights for a long time, you’ve probably heard the phrase “the (shot) group follows the light.” It’s not uncommon for shooters to find themselves hitting left of point of aim when the sunlight is coming strongly from their left. Ain’t nothin’ magical or metaphysical about it — it’s the result of an optical illusion.

You’ll see it most commonly with plain black front sights, whether of post or ramp configuration. The sunlight strongly hits the left side of the post, creating a silvery line at the edge of the black body of the front sight. Your eye and brain perceive the sliver as not being there at all; the black body appears to be the whole of the front sight, and it now appears to be right of center in the rear sight notch. Accordingly, the shooter moves the front sight — and therefore the muzzle — proportionally to the left. Not surprisingly, the shots now go to the port side too.

Sometimes your eyes and sights can fool your brain! We used a cable release for this one — no cameras or cameramen were threatened for this photo! Photo: Roy Huntington

The Bigger, Closer Effect

A little over 30 years ago I was near the Timbavati River in South Africa’s Eastern Transvaal with my older daughter. We were running low on provisions when we spotted a young impala at what I guessed was 100 yards away. Butt forward on my left hip was a 4″ Smith & Wesson Model 629 .44 Magnum in a Milt Sparks #1AT holster.

The day before we’d verified point of aim/point of impact with it at exactly that distance with J.D. Jones’ superb 320-gr. hardcast SSK bullets. I put the red ramp insert of the S&W on the impala’s spine and carefully rolled the trigger back double action. The animal fell. I still can’t help but smile when I remember my 10-year-old daughter’s exclamation at that moment: “Dad! You hit it!”

When we reached the animal, it was down but the pupils of its eyes hadn’t yet “blown,” so I put another shot into the base of its skull for a total “lights-out.” The first SSK bullet had broken the spine and taken both lungs. A decent shot but most interestingly, the distance turned out to be 117 of my paces, and 120 paces for Bierke Roux, our guide. I had thought the animal was about 20 percent closer than it actually was.

Explanation? Simple: Tunnel vision. It happens much more often in self-defense shooting cases. In four decades of working as an expert witness for the courts in shooting cases, I’ve lost count of the instances where the shooter told investigators he thought the attacker was three feet away when he fired, and it turned out they were actually closer to three yards apart. The defender will also frequently recall the assailant being larger than he actually was, or, the opponent’s gun or knife being larger than it turned out to really be.

Here’s why: Ophthalmologists tell me if we have normal binocular vision, we go through life seeing things as if through the viewfinder of a 35mm semi-wide angle lens on a single lens reflex camera. When something important captures our attention, however, tunnel vision makes it seem as if someone has replaced this with a zoom lens. The doctors tell me it’s a function of cortical perception: the eyes still see, but the brain is screening out anything extraneous to that which has captured our attention.

We go through life determining distance and the size of things by how large they appear vis-à-vis their background and surroundings. The optical illusion effect of tunnel vision is something like when you watch a baseball game and the broadcasters cut to the camera that’s located behind the catcher so you can see him — with the batter and pitcher all in the same frame. They look as if they’re on top of each other, even though you know how far they are from one another on a regulation baseball field. It’s a classic example of how tunnel vision can distort perspective, making things appear closer and larger.

The arrow shows reflection from lateral light tricking the eye into thinking the front sight has to move farther left. The revolver is an S&W Model 442.

What It All Means …

On the range, know to look for that little sliver of light reflecting on the edge of your front sight. Adjust accordingly — aim with the whole front sight including the sliver now that you know to look for it. Your shots should come back to center instead of “following the sun.”

In the field, make sure you know your trajectory and where your bullet will strike if your estimation of distance is off by a given amount.

Finally, on the street, never attempt to answer questions like “Exactly how far apart were you when you shot him?” Such basic data — even things like how many shots were fired, or exactly what words were uttered in one sequence — will almost never be correct due to the stress effects of a life-threatening encounter.