Single- and Two-Stage Triggers

Maybe one should be in your future?

Triggers on most current bolt-action hunting rifles are single stage. To fire the rifle, the trigger finger applies continually increasing pressure on the trigger until it suddenly releases, or “breaks.” Such triggers have been the standard since roughly the end of WWII. Many shooters have never used any other style.

Prior to WWII, hunting rifles generally did not have very good triggers. With many designs, the trigger itself engaged the sear when the rifle was cocked and had to be dragged out of the sear notch against strong mainspring pressure. This was not necessarily considered a fault. A heavy trigger pull was safer against unintentional discharge, especially when the hunter might have cold hands. Since practical accuracy was limited by the open iron sights found on most hunting rifles, hunters didn’t give a lot of thought to trigger quality.

Double Set

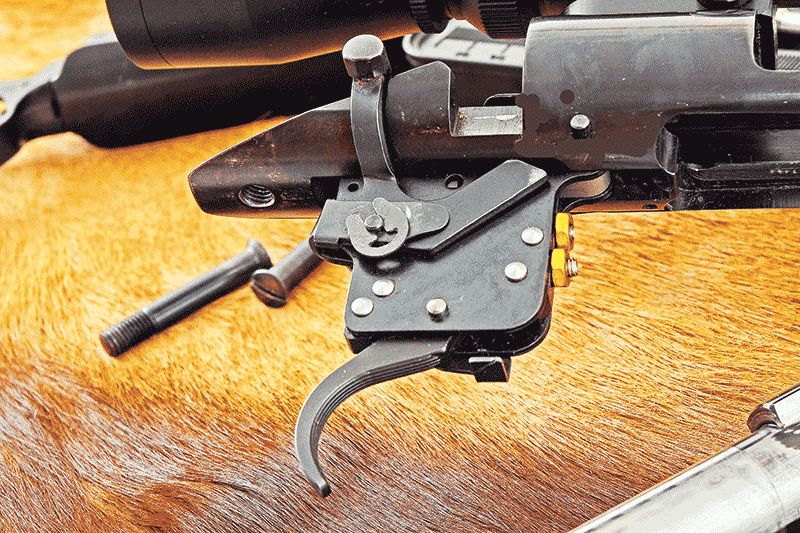

Shooters obsessed with accuracy, then as now, were trigger fussbudgets. Serious accuracy enthusiasts often went to “set” triggers. Double-set triggers had two triggers, one behind the other. Pulling one trigger, usually the rear one, set the other trigger for a very light pull, usually measured in ounces. A light pressure on the set trigger fired the piece. Single-set triggers had one trigger that was pushed forward to set the mechanism, after which a light pressure would fire the rifle.

We shouldn’t think the shooters of the prewar era weren’t aware of the virtues of a quality single-stage trigger. Anyone who has ever fired a cocked Smith & Wesson revolver has experienced a single-stage pull about as good as it gets. With properly fitted components, the trigger release of a cocked revolver is a joy. Increase pressure on the trigger and the shot breaks with almost imperceptible trigger movement and over travel.

Two Stages

Designers of military rifles had a different solution, a two-stage trigger pull. This effectively divided the trigger pull into two parts: “first pressure” and “second pressure” to use the British military terms. First pressure would move the trigger back roughly 1/4″ to 1/2″ until it reached a positive stop. While confirming sight picture, the shooter would take up the second pressure to a relatively crisp release with minimal farther trigger travel. Two-stage triggers were standard on most bolt-action military rifles for as long as such rifles were in service.

When I was reading gun magazines in the early ’60s, it was more or less settled wisdom to consider single-stage triggers superior, while two-stage triggers were as out of place on a sporting rifle as a bayonet lug. Actually the two-stage trigger was a clever design and served the needs of military rifles quite well. It was a good safety feature for soldiers often new to shooting; substantial sear engagement helped ensure against the rifle firing from heavy impact, for example, when being used in hand-to-hand fighting. The long trigger pull with two separate components was some assurance against unintentional firing. Protecting soldiers from being accidentally shot by their comrades is one thing military leaders and individual soldiers agree on.

Game Oon

How did the two-stage trigger serve in the heat of battle? In his wonderful account of his WWII service in the British 14th Army (“Quartered Safe Out Here”), author George MacDonald Fraser writes of a pitched battle with large numbers of soldiers in full view. “There wasn’t much time, but enough: to pick a target, hang for an instant on the aim to make sure, take the first pressure according to the manual — and then the second.” Later he recounts how technique gets forgotten in the rage of battle. “First pressure and second pressure is all very well for the first five shots, but by the time I was at the bottom of my magazine I must have been snatching the trigger …”

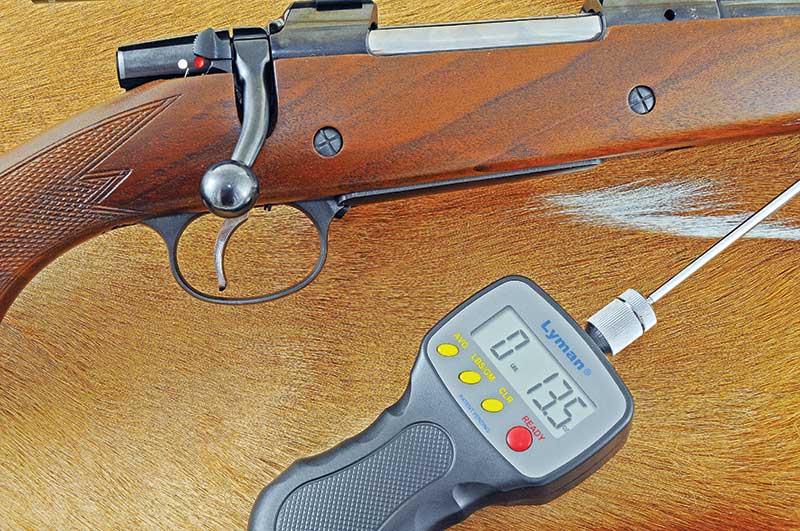

Currently two-stage triggers are making something of a comeback. The Weatherby Vanguard and some Ruger, Steyr and Tikka models have two-stage triggers, as do some replacement triggers for AR rifles. These triggers have a short, smooth, first stage and a crisp second stage. I like the feel of these triggers much better than older designs such as the Lee Enfield. They let manufacturers provide us with triggers both safe and quite light — several examples I’ve purchased have very good trigger releases in the 3-lb. range right out of the box, and can be adjusted to around 2 lbs. After hundreds of thousands of live and dry fires with my 1911-style competition pistols, taking up trigger slack followed by a crisp trigger break — “prep-press” — has become almost second nature. What might be called the modern two-stage trigger has a lot going for it. Maybe we’ve been wrong all these years!