Marlin 1895 SBL

Is It Really A Marlin? You Bet — And More!

“We’re mighty proud of it,” said Mark Gurney. “But it’s not a Ruger Marlin. It’s a Marlin.”

That’s as concise an intro to the SBL (stainless big-loop) rifle as you’ll get from the company that bought Marlin after the bankruptcy auction of the Remington Outdoor Corp. Marlin had been acquired by Remington Arms in December, 2007, pulling it into The Freedom Group, an investment consortium. Two years after closing Marlin’s H&R plant in Gardner, Mass. in 2008, Remington shuttered the main Marlin works in North Haven, Conn., moving production to Ilion, NY. The quality of Marlin lever rifles fell off. A production chief told me: “North Haven’s old machinery had been nursed by long-time workers, not all of whom came to Ilion. Much tooling was worn out or hard to re-install. Remington had no history with lever rifles. Our learning curve was steep.”

In July, 2020, Remington filed for its second Chapter 11 bankruptcy in two years. That fall, Judge Clifton R. Jessup, Jr. of the Northern District of Alabama approved the sale of Remington’s non-Marlin firearms business to the Roundhill Group for $13 million. Ruger got Marlin for $28.3 million.

Ruger’s intent? Use lean manufacturing methods to build traditional Marlin lever rifles to original or higher standards of quality. Quite a task! Ruger CEO Chris Killoy and VP Mickey Wilson had visited Ilion before 2020’s auction. A prompt move was imperative; winter was in the wings. Ruger’s engineers arrived to plan extraction of 40,000-lb. loads, take the measure of tooling to be transferred and ready it for the 650-mile journey. The destination was Ruger’s Mayodan, N.C. plant, where the company builds most of its bolt-action American rifles and its AR-556.

In November, Darryl Freeman, facilities chief at Mayodan, kept decommissioning crews working overtime to accomplish a two-month job in one. They did — finishing December 9 just as snow came to Ilion. The 150 tractor-trailer loads included 450-odd pallets of unfinished and out-of-spec parts. At its new digs, Marlin would be assigned a 105×180-foot cell bringing parts in a compact loop through 53 steps in lever-rifle manufacture. Materials would be fed and people stationed to make the most efficient use of space and movement.

Bruce Rozum, whom I knew when he’d headed R&D at Marlin, had moved to Ruger’s Newport, NH as chief engineer. Now he tapped North Haven’s auto-CAD drawings to design a hybrid production model holding CNC tolerances of 0.002″ on a rifle developed 125 years ago.

With a neigh-on weatherproof finish and furniture, and sporting a host of

practical touches, the Marlin 1895 SBL would be a fine choice for a hard-use

field gun! Right: With additions such as an updated Picatinny rail for optical

mounting, ghost-ring rear sights and a nickel-plated spiral bolt, the 1895 SBL

is both practical and eye-catching.

Historical Antecedence

John Mahlon Marlin was born two months after Mexican troops overran the Alamo in 1836. He turned 21 as Oliver Winchester bought all assets of the struggling Volcanic Repeating Arms Company for $40,000, re-organized them as New Haven Arms and hired B. Tyler Henry to run the shop. As Henry’s .44 repeater joined the Civil War, Marlin finished his apprenticeship as a machinist, pocketed his first weekly $1.50 paycheck, and married Martha Moore. By 1889 he’d registered 10 handgun patents.

Marlin’s first rifles, circa 1875, were based on C.H. Ballard’s 1861 single-shot. A lever-operated repeater flopped. Improved, it became the Model 1881, in .40-60 or .45-70. This 10-shot rifle was heavy and ungainly but could purge its magazine in seven seconds. Bill Cody and Doc Carver favored the 1881, though its dust cover needed work, as did cartridge transfers from the magazine to the carrier. Subsequent Marlins would eject to the side. A split carrier, with a wedge to expand it in cycling, eliminated jams.

Winchester’s discovery of young John Browning in 1883 brought it a tide of brilliant lever rifles, starting with the big-bore Model 1886. That year, Remington’s financial woes released 15-year employee Lewis L. Hepburn to Marlin. Then 54, Hepburn would bless Marlin with several lever rifles, notably the 1893 for the .30 WCF and the upscaled 1895 in .38-56, .40-65, .45-70, .45-90 and, later, .40-70. It listed for $18.50. An agile 7 ½-lb. version appeared in 1912, with the .33 WCF chambering. As good as the original 1895 was, Marlin sold only 18,000 during its 22-year run.

John Marlin died in 1901 and sons Mahlon and John Howard took charge. The Versailles Treaty brought divestment in rifle production. A new Marlin Firearms Corporation was formed in 1921. Its first catalog appeared in ’22. But re-organization costs, back taxes and a stiff mortgage forced foreclosure in 1924. New Haven businessman Frank Kenna wound up with a newly minted Marlin Firearms Company. Under his steady hand, it endured the Depression and prospered through WW II into the sunny ’50s.

Modern Marlin

In 1969 Marlin operations moved to North Haven. A new Model 1895 followed, with cut rifling (for cast bullets). A pistol-grip stock and micro-groove rifling came next. Marlin installed a cross-bolt hammer-block safety on all centerfire lever rifles. Cut checkering appeared in 1994. Variants of the 1895 included a short Guide Gun (also in .450 Marlin) and a Cowboy with a long octagon barrel.

Why the 1895? Product Manager Eric Lundgren, who’d worked at Remington, said .45-70 sales had been brisk. And Ruger’s rendition would be the only stainless lever rifle around. The more common 1893 and its 336 progeny (1948) accounted for many more sales. But ubiquity might take some shine off the first Marlin from Mayodan. “The .45-70 has enjoyed a resurgence of late,” agreed Mark Gurney. “It has big-bullet punch hunters link to close-cover hunts with lever-actions.”

The project required many hands, as infrastructure, processes and design tweaks had to be in place before the first rifle took shape. Then came thousands of rounds of testing. “Our plan was to bring Marlins to retail counters by the end of ’21,” Mark said. Marlin SBL number RM0001001 was finished September 30. A sample reached me a few months later.

In profile this rifle is unmistakably Marlin. Some features, just as clearly, depart from the original’s. A gray laminate stock cradles the all stainless steel build. The lever loop is oversize, which is handy. A Picatinny rail noses 7″ up the 19″ barrel from the rear of the receiver, where it anchors an adjustable HIVIZ ghost ring sight. The HIVIZ front sight is a green tritium-ringed fiber optic rod in a thick blade atop a beefy ramp. Rifling is hammer-forged, with a 1-in-20 twist. The muzzle is threaded 11/16×24. Its cap, with two flats for a wrench, seats seamlessly. The 6-shot magazine is dove-tailed to the barrel up front. The forend cap, with front swivel stud, fits snugly around the magazine and wood, and cups the barrel neatly.

The forend is slimmer, opposed to the 1895’s “hand-filling” wood bordering on bulbous of a few years ago. Clean point-pattern checkering around the forend and on generous grip panels keeps you in control, and comb fluting, absent on Marlins from Ilion, is back!

The SBL trigger pull is spec’d at 5 to 7 lbs. Mine breaks at just over 7, having a smooth release with no objectionable take-up. Yes, you can hold your applause for the crossbolt safety.

Cosmetic details not on previous Marlins? Besides an “RM” serial number prefix, include a fluted, nickel-plated bolt and a red center in the traditional Marlin bullseye on the buttstock’s belly. Instead of a grip cap, Ruger laser-engraved Marlin’s horse-and-rider logo from Frederick S. Remington’s 1890 painting, “Danger Ahead.” As an aside, John Marlin asked Remington for this image, absent the original work’s other figures. It first appeared on the cover of Marlin’s 1900 catalog.

Shooting

A brilliant Meopta Optika5 2-10×42 scope hopped aboard the SBL in rings just high enough to put the 1″ tube above the ghost ring sight. The front bell cleared the rail by 1/8″. I could have removed the sight to attach a scope without a front bell in lower rings. For me, the buttstock’s comb is too low even for the sights provided — and, of course, too low for the scope, which lifted the sight-line ¾”. A cheek-pad from a shooting course I took at the FTW Ranch was a perfect fix.

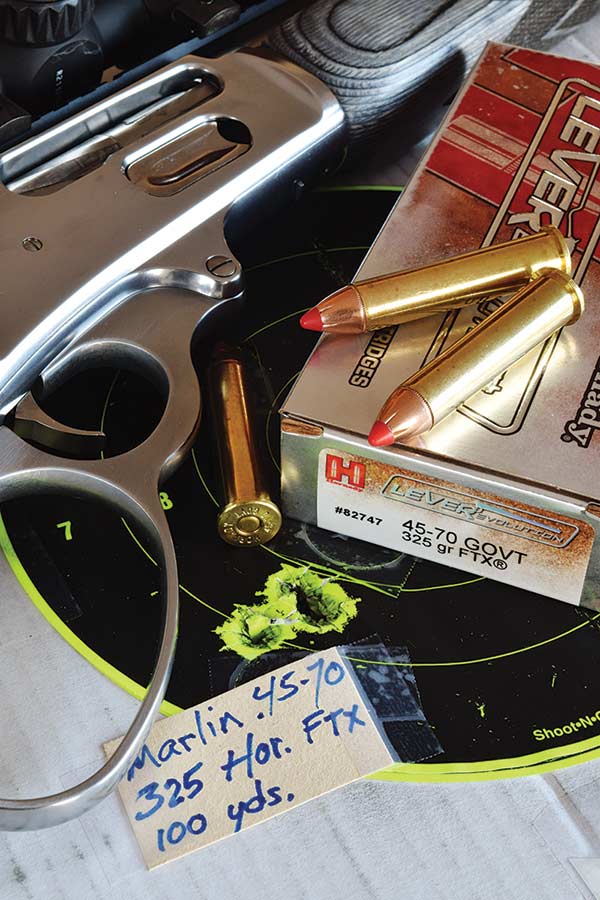

Marlin’s SBL shrugged a 405-grain bullet downrange at just over 1,300 fps, about as fast as black powder hurled the same-weight slugs from 1873 Springfields. Hornady 325-grain FTXs at 2,000 fps, Remington 300-grain SJHPs at 1,900 and Black Hills 325-grain HoneyBadgers at 1,775 spelled improvement. First 3-shot groups averaged just over an inch, with the FTXs cutting an eye-popping ¾” cloverleaf. SJHPs stayed inside 1 ¼” and deep-driving Honey Badgers almost as tight. The black 1″ recoil pad sapped the sting from these loads.

And?

The action closes crisply, and opens with a tad more effort than some lever mechanisms. But resistance is easily overcome, and doesn’t slow cycling. Thank Ruger’s attention to “stacking” — the summing of tolerances leading to a loose fit and operation. Halving individual tolerances with CNC machines reduces their “stack” and limits “slop” in an action. Tumbling components to remove burrs, Ruger ensures smooth, uniform engaging surfaces. The rifle doesn’t rattle, yet the strokes are silky. Such machining and finishing is notable, as automation figures heavily in the SBL’s manufacture. No hammers, files or manual screwdrivers are required in its assembly. Mr. Marlin would likely be amazed.

Feeding, extraction and ejection are hitch-free. “Pyramid testing catches faults before rifles reach the retail chain,” said Mark. That method means a generous sample of rifles fired, say, 1,000 times each, while a few might be chosen to fire 5,000 and a few of those to 10,000. “Stoppages caused by ammunition aren’t held against a rifle. But at Ruger any mechanical fault gets prompt attention. Perfect function is the standard,” added Mark. He added after factory trials, rifles are “jury-tested” on ranges and afield by veteran shooters. The subjective carries weight too.

I’m impressed by the SBL’s wood-to-metal fit and the receiver’s high polish. Ripples and dished screw holes show up immediately on bright surfaces. A flat finish is hard to achieve. This Marlin has it.

What’s to follow? “More Marlins,” smiled Mark. “We’ve considered about as many chamberings and configurations as you can imagine. We’re committed to the brand — and customers want the rifles.”

MSRP: $1,399

MarlinFirearms.com