Black Powder Cartridges Part II

The .45 Colt

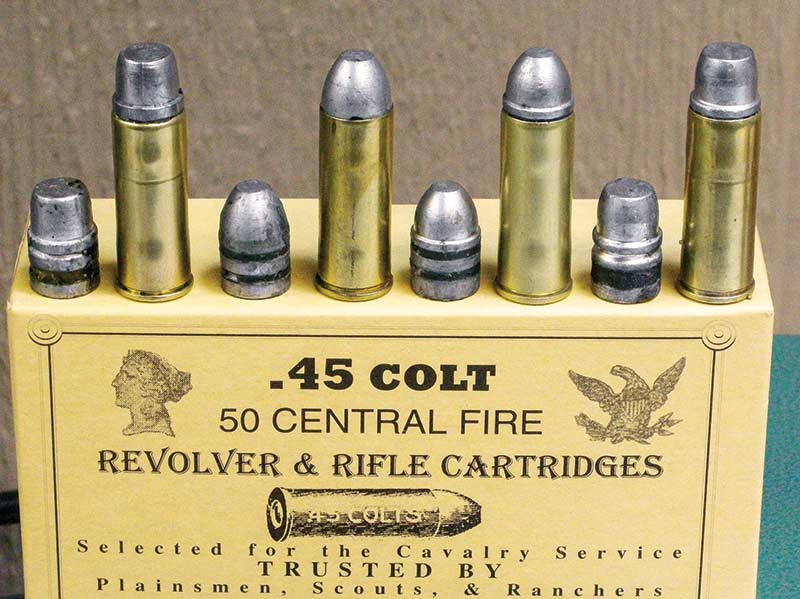

The .45 Colt cartridge consists of a 250- to 255-grain bullet over 40 grains of black powder, at least according to the prevailing wisdom. The cartridge case itself was not brass, but rather copper. It was a powerful load and still is. When I duplicated it using the old-style brass, the muzzle velocity was well over 1,000 fps in a 71/2″ Single Action Army, the standard issue at the time.

I especially appreciate shooting the 7 1/2″ Colt; it is almost spiritual bonding with the Old West. Anyone who can fire a Cavalry Model with the original loads — and not feel something — needs to take two aspirin and go to bed. The military soon dropped the powder charge from 40 grains to 30 grains and if a civilian went into a local store to purchase .45 Colt cartridges, he probably received those loaded with 35 grains. There might be a message in there somewhere.

Head Games

The brass at the time has come to be known as balloon-head brass, meaning the primer pocket protrudes into the case itself. It remained this way until around 1950 when the case heads became solid brass and also the cartridge case itself was given a stronger rim.

Today’s brass, such as Starline .45 Colt, cannot be loaded with a full 40 grains of black powder with a traditional bullet such as Lyman’s #454190 or the Lachmiller #45-255m, both of which must be seated relatively deep into the case and then crimped over the ogive. There are those who report using 40 grains in currently manufactured .45 Colt brass; however, they do not do it with a traditional bullet but rather a modern design that has a crimping groove. Also, much of the bullet weight is out in front of the cartridge case with minimum mass inside the case. When using currently manufactured brass, I top out at 37.5 grains of black powder; it gives right at 925–950 fps.

For loading black powder cartridges, I start as I do with any sixgun loads. I full-length resize the brass, whether it be fired or brand-new, expand the case mouth and seat a new primer, preferably a Magnum primer to help with ignition. Now things change as we approach charging the cases with powder. Should conventional plastic powder measures such as from Lyman and RCBS be used in loading black powder? The possible problem is the fact these examples have plastic hoppers. It’s possible for a spark from the combination of plastic and black powder to set off an explosion. There are those who say it can happen and others who say it can’t. I prefer to err on the side of caution and use aluminum hoppers.

Fellow GUNS writer Duke Venturino said he was loading one day and realized how much powder was close to his face and thus decided against using a plastic hopper. I’m not in near as much a hurry as I used to be, so most — actually, all — of my black powder cartridges are now charged with powder using the Lee Powder Measure Kit, a series of powder scoops of different sizes. They are measured in cubic centimeters and the kit has about a dozen ranging from 0.5 cc to 3.4 cc. The ones I find useful for loading .45 Colt Black Powder are 1.9 cc and 2.2 cc which hold 30.0 and 36.5 grains of FFFg black powder by volume.

On The Blocks

Placing the cartridges in a loading block, I use the desired dipper and a small funnel to place the powder in each case. Then I normally place a wad such as Ox-Yoke provides on top of the powder before seating the bullet. These are the same wads I use when loading percussion revolvers. I also have Thompson Wads that contain more lube. These work fine for percussion revolvers; however when used with cartridges, they should be shot and not stored for a long period of time as the lube will work its way into the powder.

Shooting black powder is enjoyable, very much so at least for me, but it is dirty. It fouls the barrel easily and requires extensive cleaning after each shooting session. The wad helps cut down on fouling. I also choose a bullet featuring a large, deep lube groove. It is mated with lube especially designed for black powder such as SPG or Lyman Black Powder Gold that helps to keep this fouling soft. If time permits, I also run a soaked patch down the barrel after every cylinder full.

If one uses conventional bullets normally lubed with standard lubes, and does not use wads and does not swab the barrel, the result will be a buildup of powder fouling that will destroy accuracy. Even worse, if allowed to go too far, the fouling will build up in the barrel like coal deposits and be just about as difficult to remove. The use of proper lubes and swabbing out the barrel makes cleanup relatively easy after each session. Cleanup is also made easier by the use of stainless steel or nickel-plated sixguns. These are readily available in replica form.

Fine Grind

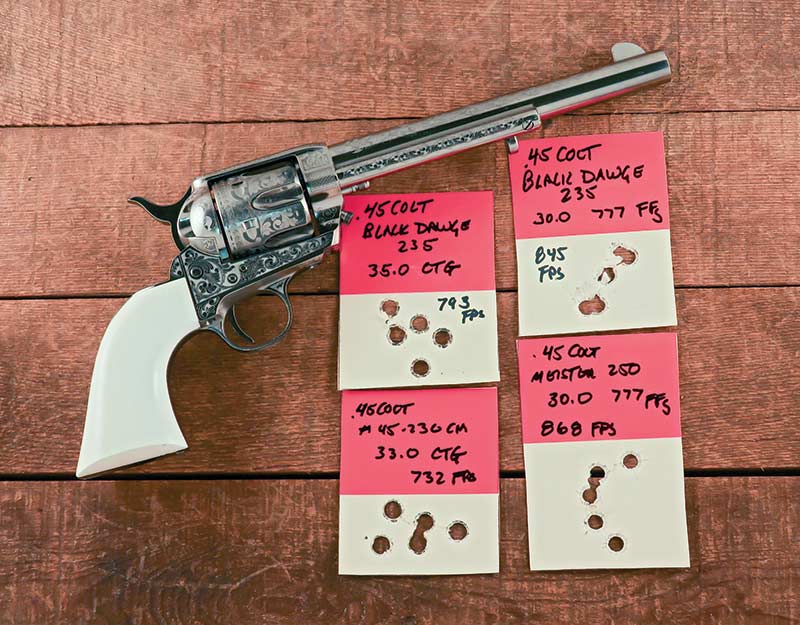

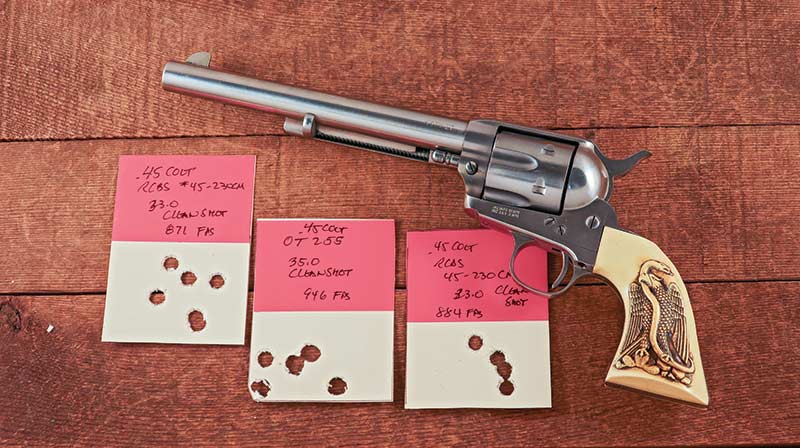

Over the years I have used five different brands of black powder in both FFg and FFFg granulations. The more “Fs” the finer the granulation. Fg and FFFFg are also available; however, the two middle granulations are best suited to sixgun cartridges. To give an idea of what muzzle velocities can be expected from a 7 1/2″ sixgun, we look at charges of 30.0, 35.0 and 37.5 grains.

With GOEX, FFg muzzle velocities are 773 fps, 872 fps and 928 fps, respectively. Switching to FFFg, these velocities are 804 fps, 919 fps and 962 fps — the same amounts of Pyrodex P come in at 865 fps, 929 fps and 987 fps. These are all with a 250-grain bullet. When one considers the standard .45 ACP is a 230-grain bullet at 820 fps, we can readily see how powerful these loads are.

As this is written, it has become very difficult to find real black powder, so most of my loading and shooting is with black powder substitutes, saving my black powder for percussion sixguns. They work just fine and in most cases give a little extra muzzle velocity. They still will foul the barrel and require cleaning just as with black powder. I have had especially excellent results with Clean Shot and I don’t know if this one is even available anymore.