PEACEMAKERS & SCHOFIELDS

There’s been plenty of hullabaloo

over which is the superior design.

Duke has spent considerable time studying and shooting the types of handguns carried by the US Cavalry.

His collection includes (from left to right) an original Smith & Wesson Model No. 3 Schofield, a new

Smith & Wesson Model No. 3 Schofield, a Colt 1873/1973 Peacemaker Commemorative, and a

US Firearms “Custer Battlefield” single action .45.

Some time ago in another gun magazine, a writer said something to the effect, “Although Smith & Wesson’s Model No. 3 Schofield was a superior design, the Colt SAA got the government contracts.”

Brothers, I beg to differ! The Smith & Wesson Model No. 3 Schofield was indeed a more complicated design. It can even be argued it was made with better craftsmanship than the Colt SAA. But, to say it was a “superior design” for issue to horse cavalrymen is just so much non-sense. Making such a statement shows a fundamental lack of understanding about the rigors of horseback travel, and the corresponding wear and tear all horse troopers’ equipment suffered after months of campaigning in the American West.

Think about it like this. If you were going to depend on a firearm for saving your life, would you prefer an intricate one with myriad small parts, or a robust but simply made one with just a few stout parts? The first would be the S&W Schofield, and the latter would be the Colt SAA, which also came to bear the moniker Peacemaker.

The Colt

Here are the basic details of each type of revolver as purchased by the US Government circa 1873-1875 for issue to cavalry regiments. The Colt SAA was a single-action revolver with a 71⁄2″ barrel, 6-shot cylinder and was fitted with a solid piece of walnut for grips. (They were inlet so the grip frame fit around them.)

To load it, the hammer is pulled to a half-cock notch which frees its cylinder for rotation and then each chamber is loaded singly through a loading gate on the frame’s right side. The empty cases are punched out of the chambers one at a time by an ejector rod through the same loading gate. Its main frame and hammer were color case-hardened and the rest of the hand-gun was given a blue finish.

The S&W

The Smith & Wesson Schofield was also a single-action revolver with a 7″ barrel and 6-shot cylinder. Its grips were two small slabs of walnut held to the frame by a single screw. To load it the hammer was half-cocked, then a frame mounted latch above the hammer must be pulled back and the barrel pushed downwards. An ejector pushes empty cases up and hopefully clear of the chambers. Then fresh rounds are inserted — again one at a time. The S&W Schofield’s finish was full blue with color case-hardened hammer, trigger and barrel latch.

A word about the cartridges of these two handguns is in order. They were both .45 caliber, with the Colt taking a cartridge case 1.29″ in length. Original military loads for it used a 250-grain bullet over 30 grains of black powder. (Not 40 grains as often written!) The S&W Schofield’s cylinder was too short for the cartridge and, furthermore, Colt’s .45 caliber cartridge cases had a bare nubbin for a rim. It did not give enough purchase for the S&W’s ejector star to grab. Therefore, the Schofield revolvers were chambered for a 45-caliber cartridge with case length of only 1.10″.

In military loads, bullet weight was reduced to 230 grains and powder charge to 28 grains. Additionally, the S&W .45 cartridge case’s rim was widened about .020″ so as to work reliably with the star extractor. Both of these .45 caliber cartridges would feed and function perfectly in the Colt SAA but only the .45 S&W would work in the Schofield.

In my personal opinion, after duplicating the military loads of both types and shooting hundreds of them, I would call it a tie. They were both fine cartridges for a fighting handgun of the era.

Interestingly, it should be noted the government’s Frankford Arsenal was instructed to quit making the longer .45 Colt cartridge as early as August 1874, and concentrated on producing the .45 S&W version for many years thereafter.

What about the much vaunted ability of the Schofield to simultaneously eject all fired cartridges? That was good if it indeed occurred. However, if the revolver is operated in a straight upright position such does not always happen. Even the wider rims of the .45 S&W cases will sometimes slip under the extractor, and tie up the works.

I have found for perfect extraction the Schofield must be opened with a “throw-away” motion to the front so the empty cases clear the mechanism. With just a little practice the Colt SAA can be cleared of fired cartridges in about three to four seconds. Since there was no such thing as speed loaders in the 1870s, both types of revolver had to be reloaded one round at a time.

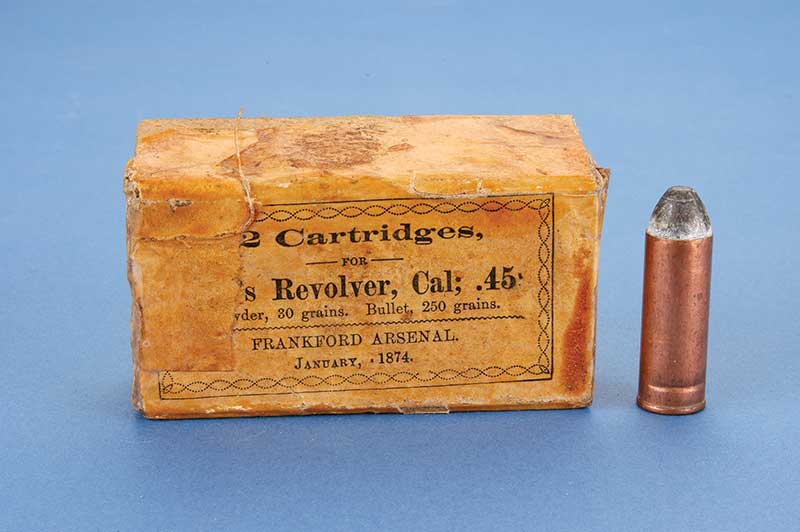

This box of original US Army .45 Colt cartridges from 1874 (above) is loaded with a 30-grain

powder charge and 250-grain bullet in an inside-primed copper case. Duke considers the

effectiveness of the original military loadings a tie. Here (below, from left to right), an original

military .45 Colt cartridge, original .45 S&W cartridge, commercial .45 Colt cartridge and

commercial .45 S&W cartridge.

One Hand Gun

The Schofield’s major advantage to a cavalry trooper was that it could be operated with one hand while the other retained control of the horse’s reins. The barrel latch could be pulled back with a thumb and then the barrel could be pushed downwards by brushing it against one’s side or even a saddle. Then the handgun could be tucked under into the offside armpit so cartridges could be slipped into the chambers. The Colt SAA requires two hands to operate.

Another minus on the Colt’s score were the six screws attaching the grip frame to the main frame. There was a reason each Colt SAA was issued with a screwdriver.

Those six screws require regular tightening. The Schofield had no such screws holding the grip frame to the rest of the gun. The Colt’s major advantage was its barrel screwed directly into its big solid frame. That arrangement could be jingled about on horseback until there’s ice water in hell and it won’t come loose. The Schofield’s barrel is attached to its frame by a pivoting hinge. It was easy for them to develop lateral play. Put it this way —there are many 1870’s issue Colt SAAs as tight as the day they left the factory. It’s rare to see a Schofield (one actually issued) whose barrel doesn’t have some wobble. Some of them are so loose in regards to the frame they are comical.

The Last Word

A Colt SAA in which one of the few internal parts have broken or become worn can easily be repaired by someone with only cursory knowledge of the sixgun. The Colt Peacemaker could easily have been repaired by an armorer at a fort or by a frontier gunsmith. Its timing may not have been perfect then, but the gun would be operational. Conversely, a Smith & Wesson Schofield with its myriad small parts and springs must be turned over to a trained professional for repair. That most likely meant a return trip to the factory or at least a gunsmith at one of the government’s arsenals.

The Smith & Wesson Model No. 3 Schofield was a fine revolver — probably a design ahead of its time. But, it was not a prime choice for someone traveling into out of the way places for months at a time — on horseback no less. The US Army officers on the testing board knew precisely what they were doing in picking the sturdy and simple Colt SAA aka Peacemaker for cavalry service in the 1870s.

Get More Revolver Content Every Week!

Sign up for the Wheelgun Wednesday newsletter here: