The Hard Way

The Internet Has Definitely Changed Gun Repair

I know I sound like a “boomer” when I say “Nobody learns the hard way anymore,” but it’s simply true. Nowadays, failure is not an option. But back in my day, failure was the rule rather than the exception — especially if you were talking guns.

The reason is simple: Today, the instructions for anything from abdominal surgery to zebra taxidermy are easily found on the internet. Furthermore, if you visit YouTube, the odds are about one in one there will be several videos of varying quality demonstrating the entire process in Glorious Technicolor detail.

Our modern age of communication is one major reason I haven’t ruined a firearm in at least 10 years. My “gun closet” was once a graveyard of partially disassembled shotguns sitting among boogered-up screws, leftover coil springs and mystery objects that resemble either an extractor from a Dickson Detective .32 ACP or part of a ball point pen. Nowadays, with the internet, launching blindly into a misguided repair isn’t a big deal unless your Wi-Fi goes out, but it wasn’t always that way.

Streaming Near You

Before the days of the interweb, we learned things purely by trial and error — mostly error. There were books and formal training courses available, but we didn’t know how to find any of them and probably couldn’t have afforded it anyway. In the meantime, if our rifle needed fixing, we just tackled the job ourselves. By taking on such projects, we gained the insights, confidence and self-satisfaction of doing a job yourself, learning as we went. And when you were finished, there was an immeasurable sense of pride. Granted, the rifle was still broken — and now fully automatic, and ejected spent casings through rear sight — but we learned. Mostly, we learned we didn’t know what we were doing.

In the pre-internet days, kids like me took things apart just to see how they were put together. I was especially bad in this regard, especially with fishing reels. Since there were no diagrams available, the only way to find out what was hiding inside was to grab a screwdriver and go at it, which I did at every turn. This is why I was locally known as “The kid with the fishing reel that sounds like a rock crusher.” It was full-auto, too.

I had such drive to disassemble that my sainted Grandfather often took me to a used furniture store in town to buy old clocks and other small appliances just so I could practice taking them apart. In hindsight, this was purely a defensive measure to make sure I didn’t practice on any of his stuff. It mostly worked.

Springing Into Action

With a mechanical clock sedated in front of me on the kitchen table, I started out carefully, methodically, thoughtfully, like a budding surgeon. I carefully removed parts, making mental note of how they fit into the big picture and then laid them in chronological order alongside their associated screws. I’d like to claim I eventually reduced the clock to a bare frame and then carefully reassembled it, but old-school tinkerers know what always happened.

At some point, I’d make the near-fatal mistake of removing the one certain screw which unleashed The Kraken. This was otherwise known as the Mainspring, a 14-mile-long beast of spring-tempered steel which attempted to blind me or slice my jugular vein, sometimes both. While I was running for my life, I’d accidentally scatter the carefully arranged parts so even Humpty Dumpty’s minions and various equines couldn’t get the clock back together — even if they had access to the internet.

Those early attempts at “repair” taught me an important lesson: Springs are hateful things.

Later, when I attended my first pistol armorer school, one of the first modules was regarding “Dammit Springs.” The instructor explained every firearm contained tiny springs which tend to suddenly leap from the gun and cavort across the workbench until they skitter into the most inaccessible spot possible. Meanwhile, you instantly exclaim “Dammit!” thus the name.

Tiny screws are nearly as bad. They don’t often leap from the gun like springs but when removed, they have a strong tendency to embrace their newfound freedom by hiding in the nearest carpeting or scurrying under the biggest piece of furniture. They are also the chameleon of the gun world because they have an ability to instantly change their appearance to match patterns in the flooring or bits of debris.

Folks today don’t learn about such things the hard way. Instead, they watch YouTube because, regardless of whether you’re fixing an outboard motor or a heart-lung machine, there is an experienced technician with an extensive video channel devoted to the very task you’re attempting. As a single example, I now understand the basics of submersible pumps because I recently became fascinated with, you guessed it, a channel devoted to residential water wells. In the old days, I would have needed to purchase a drilling rig and spend a couple of decades learning the trade, but now I learned all the intricacies of the business on my phone.

Tool Time

One thing I’ve learned the hard way is repairs — in general and gun repairs in particular — require the right tools. In the case of firearms, my early experiences demonstrated to me that a set of gunsmith screwdrivers isn’t a luxury.

I base this one on many, many pristine firearms I’ve committed gunsmithing upon, turning a beautiful factory swan into an ugly duckling by maiming the action screws until they look like they’ve been gnawed on by beavers. Even if I fixed the problem and got the gun back together in proper sequence — rare — it was still scarred for life.

Have you ever seen a classic LeFever Shotgun weeping on the bench? I have, and it’s not pretty.

I wish we had YouTube when I was a young person because I would have understood the importance of a good set of gunsmith screwdrivers. I still wouldn’t have bought any because I was always dead broke, but at least I would have known better. Things Are Different Now

Through a lifetime of working on firearms without the slightest clue of what I was doing, I learned many things folks today take for granted because today they learn from experts doing things The Right Way on the “tube.” Some of these lessons are —

• Don’t use a scope as the lever to install your twist-in rings unless you want to experience the challenge of permanent 14 MOA left windage.

• Files are useful but dangerous, especially if you don’t want your gun to unexpectedly fire whenever the barometer changes.

• There is always one part not available to fix your gun. Even if you are the Director of NASA and asked your crack team of rocket scientists to fix your gun, after a six-year, multi-billion dollar effort they’d discover the necessary cylinder pawl hasn’t been in stock since 1968.

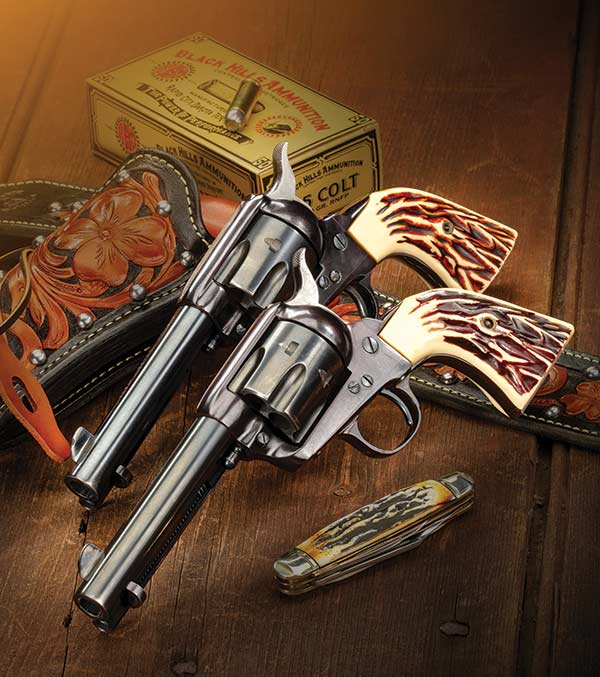

• Revolvers — just don’t. Never. I know some people like Roy Huntington routinely build high-quality revolvers from pieces of old railroad rail, but normal people can’t, even with assistance from YouTube.

Things Are Different Now

When you consider how deeply the internet has changed the process of working on guns and weaponry, I can only imagine cinematic spy thrillers of the future — “Mr. Bond, we only have three minutes before this Mark VII Mod 3 multiple-warhead nuclear device turns us into radioactive grit. We need to run!”

“No, my darling Love Interest with an Utterly Provocative Name, I’ll just watch one of these online videos and have it defused before you can even begin to remove your blouse …”

And he will — and she will too — but this new smartphone-driven process just doesn’t have the same panache as the way we used to do things. Granted, trying to dismantle a bomb like we did in pre-internet days meant Mr. Bond would end up as radioactive grit, but at least he would have learned a couple of things in the process.

For instance, how much you hurt the resale value of a nuclear warhead by boogering up the screws.