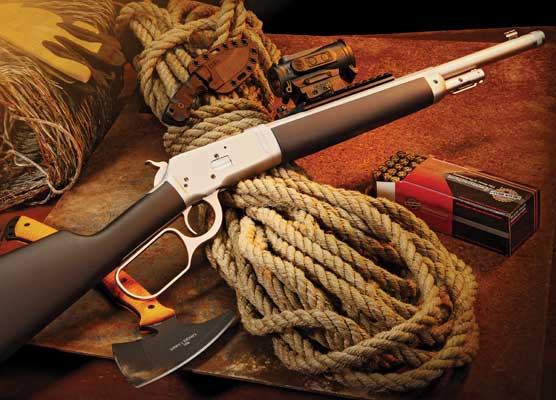

Winchester Enigma

Marlin rifles had clear advantages — didn’t they?

In 1963 I learned life is not fair. Bruce had been absent a week. A lot of classes to miss. A lot to make up. But then he returned, a broad grin splitting cheeks red from November’s wind. Details came soon enough. He’d been given — given! — a Winchester 94 .30-30, and hied off with his father to the clan’s deer camp in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. There, on opening day, he’d used his new rifle to kill an eight-point buck — an eight-pointer!

My father didn’t hunt. His only concession to my pestering had been a Daisy BB gun. The moon would turn to cheese before I owned a Winchester or shot a deer. How I envied Bruce the Blessed!

By all accounts, the moon is not yet cheese but the fates must have smiled as there’s a Winchester .30-30 in my rack and antlers on the wall.

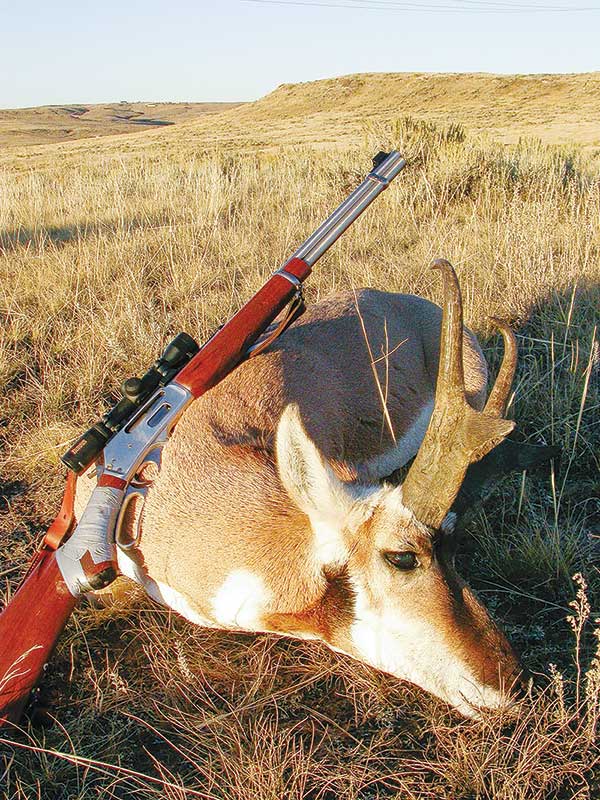

Then again, that 94 endures the company of several Marlin lever-actions. And while my Marlins have killed deer, bear, elk and pronghorn, I’ve taken just one buck with Winchester’s classic deer rifle.

Winchester

I’ve nothing against Winchester. In fact, its Browning-designed repeaters, Models 1886 to 1895, have long impressed me as some of the greatest sporting arms ever. It’s a common reverence, given the sales of Winchesters and look-alikes.

“The Winchester, stocked and sighted to suit myself,” wrote Theodore Roosevelt, “is by all odds the best weapon I ever had, and I now use it almost exclusively, having killed every kind of game with it …. [It] is deadly, accurate … stands very rough usage and is unapproachable for the rapidity of its fire.”

By the time Roosevelt wrote 39 books (six on hunting), “Winchester” was shorthand for a lever-action rifle. From the first to bear the Winchester name, the Model 1866, to the 1895 accompanying T.R. and son Kermit on safari, lever rifles defined the brand.

Those rifles date to 1848, a decade before Roosevelt’s birth. Stephen Taylor’s hollow-base bullet, (with powder inside), then Walter Hunt’s “Rocket Ball” and “Volitional” repeating rifle preceded development of the metallic cartridge by Smith and Wesson. They refined the Hunt rifle after Lewis Jennings improved it, and in 1854 formed a partnership with financier Courtland Palmer. The next year, 40 investors bought them out to form the Volcanic Repeating Arms Company. Oliver Winchester became director and moved Volcanic to New Haven, Conn. When sluggish sales threatened bankruptcy in 1857, he bought all assets for $40,000 to found the New Haven Arms Company. In 1860 its gunsmith, Benjamin Tyler Henry, received a patent for a 15-shot repeating rifle in .44 rimfire. It would sire Winchester’s Model 1866. The following Model 1873 fired the .44 WCF (.44-40), Winchester’s first centerfire cartridge. In 1878, Colt so chambered its Single Action Army revolver.

Popular on homesteads and both sides of the law, the .44-40 was soon said to have claimed more lives, human and animal, than any other cartridge. Winchester and Colt had become more than brands.

Not that Winchester’s 1873 was perfect. New Hampshire native William Wright had gone west in 1883 to explore the northern Rockies, where he’d later guide hunters. His study of grizzly bears inspired a book published in 1909 but his first grizzly was almost his last. Hunting elk along a high-country creek, he spied a bear. It lumbered by at 40 steps. He fired. The beast charged. When his rifle’s extractor failed, Wright leaped into the freezing creek and submerged to his chin tight under the bank’s lip. At last, driven by bone-biting cold to climb ashore, he found the grizzly dead. He pried the spent .44 case free.

The Winchester Model 1876 was in many ways an outsize 1873 for the .45-75 WCF. Roosevelt evidently bought one — his first rifle — when he was 22. With the means to indulge his tastes, TR would order options like fine checkered walnut and case-colored steel, half-octagon barrels and half-magazines, pistol grips and shotgun butts. Famed engraver John Ulrich embellished his oft-photographed 1876. It had a crescent cheek-piece, Freund sights.

“I don’t know how to shoot well, but I know how to shoot often!” Roosevelt needed eyeglasses and freely admitted he liked lever-actions because they could be cycled fast from the shoulder!

Winchester’s Model 1876 was heavy but not stout enough for loads popular in Remington and Sharps single-shots. It lasted a decade. Its sequel: a dropping-block rifle designed by an unknown Utahn still in his 20s. Over the next 17 years (1884-1900), John Browning would bring Winchester 40 firearms, including the 1886, 1892, 1894 and 1895 lever-action rifles.

Making Marlin

Meanwhile, John Mahlon Marlin, 19 years older than Browning, was in the last half of his career. Born in 1836, two months to the day after Mexican troops overran defenders of the Alamo, he’d grown up in Connecticut’s gun industry. His first paycheck, after six months as apprentice machinist, was $1.50 per week! He labored over pistols and may have worked briefly for Colt. His first gun patents, February 8 and April 5, 1870, show a Hartford address. They would launch the Marlin brand.

From 1863 to 1880, Marlin sold 16,000 “Never Miss” and “Victor” Derringer-style single-shots. In 1870 he added “OK” and “Little Joker” spur-trigger revolvers in .22 Short. More potent pistols followed.

Beginning in 1875, Marlin built rifles on the 1861 Ballard action. The underhammer, lever-driven repeater flopped. Its 1882 progeny became the Model 1881 six years later. This 10-shot, side-loading, top-ejecting lever rifle was bored to .45-70 and .40-60. A small-frame version came in .32-40 and .38-55.

The Marlin 1881 started well in military trials, firing 10 shots in seven seconds. Then a cartridge exploded in the magazine. There were no injuries; no cause was given but the Army withheld approval.

The gun used a split carrier with a wedge to expand it in cycling, improving cartridge transfer from magazine to carrier. Marlin produced 20,000 Model 1881s.

Like Winchester, John Marlin’s firm got help from a firearms wizard. Lewis L. Hepburn had built muzzle-loading rifles until, at age 39 in 1871, Remington hired him. Result: the Remington-Hepburn No. 3 single-shot rifle. The company’s 1886 fiscal woes sent Hepburn to Marlin, where his engineering talents were pivotal to the design of its lever-action Models 1888, 1889, 1891, 1892, 1893, 1894, 1895 and 1897. The Model 1888 in .32-20, .38-40 and .44-40 held 16 rounds under a 24″ barrel and cost $18. Fewer than 5,000 shipped before Marlin dropped it in 1892. The side-ejecting Model 1889 in the same chamberings sold 55,000 rifles. The Hepburn-designed 1891, in .22 and .32, was Marlin’s first successful lever-action rimfire. Exhibition shooting by Annie Oakley gave this $18 rifle and its 1892 sequel a boost.

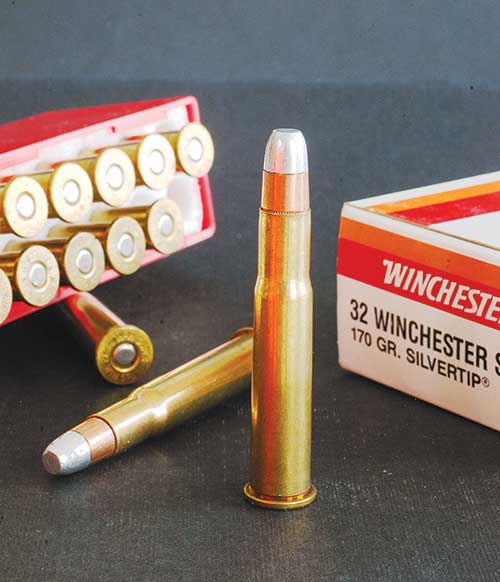

In the 1890s Marlin and Winchester competed directly at market. While Marlin’s 1889 performed well, it couldn’t match the power or sales potential of Winchester’s ’86. Nor had the Marlin brand earned celebrity in saddle scabbards during the closing decade of the Old West. But the 1893 Marlin ($13.35 to start) handled the same cartridge class as Winchester’s 1894: .32-40 and .38-55 initially, then .25-36. The .30-30 and .32 Special would follow in 1922, after the war interrupted Model 1893 production. Marlin’s short-action 1894 in .25-20, .32-20, .38-40 and .44-40 sparred ably with Winchester’s Model 1892. Still, sales targets pressured its debut price of $18 down to $10.40 in 1901!

In its Model 1895, Marlin offered an alternative to the Winchester 1886. Bored to .38-56, .40-65, .45-70, .45-90 and, later, .40-70, it cost $18.50, with a $3.50 premium for take-down rifles. In 1912 the .33 WCF joined the roster, appearing also in a lightweight (7½-lb.) version.

Marlin’s success with take-down rifles prompted its Model 1897 lever-action .22. It would be one of Lewis Hepburn’s last projects. A fall on ice in January 1910, broke his hip. It did not heal. Bedridden, the gifted inventor who’d contributed so much to Marlin died in August, 1914.

In 1936 Marlin gave its Model 1893 a facelift. Dubbed Model 1936, then Model 36 the following year, it listed for $32. The Model 336, with round-bodied bolt and coil mainspring, arrived in 1948. Five years later, Marlin replaced its Ballard cut rifling with “Micro-Groove” rifling, ironed in with a tungsten carbide button. Introduced at $74, the 336 sold briskly in .30-30, also in .32 Special and .35 Remington. It struggled in .219 Zipper, a chambering dropped in 1959.

Two Choices

By the time Bruce killed his eight-pointer four years later, the Winchester-Marlin tug-o-war had narrowed to competition between Winchester’s 94 and Marlin’s 336. Neither company had a short-action (.44-40-length) lever rifle. Gone too were the big boomers. In 1935 Winchester had supplanted its Model 1886 with the Model 71 in .348. It expired 22 years later. Marlin’s 1895 had faded too.

Though Marlin would soon introduce a 336 in .44 Magnum, and Winchester would later contract a fine reproduction of its 1892, lever-rifle options were few as Bruce field-dressed his buck. That year Shooter’s Bible listed Winchester’s 94 in .30-30 or .32 Special at $83.95. A Marlin 336 in .30-30 or .35 Remington cost $86.95. Three versions of the 336, priced the same, included two with pistol-grip stocks. The Texan shared the Winchester 94 profile. Both 6½- to 7-lb. carbines had straight grip walnut stocks and full-length six-shot magazines under banded 20″ barrels. Open sights were similar.

Which Was Better?

The 336’s side ejection permitted low-over-center scope mounting. Its wraparound receiver was stronger than the Winchester’s and better shielded the action. Marlin’s .35 Remington option appealed to hunters who thought the .32 Special to be a .30-30 with an alias.

I’ve shot elk with those ballistic twins, adequate but of limited effective reach on such big beasts. The last, taken with a .32 Special, fell to one bullet through the lungs at 130 yards. It was not as notable a kill as Ed Broder’s in 1926. Late one November afternoon, he and his hunting partner reached their cabin near Chip Lake, Alberta in a Model T, then by horse-drawn sleigh. Broder made the most of the little light left. A big track in the snow led him to a buck which fell to his .32 Special. The antlers taped 355″ — still the top score for non-typical mule deer!

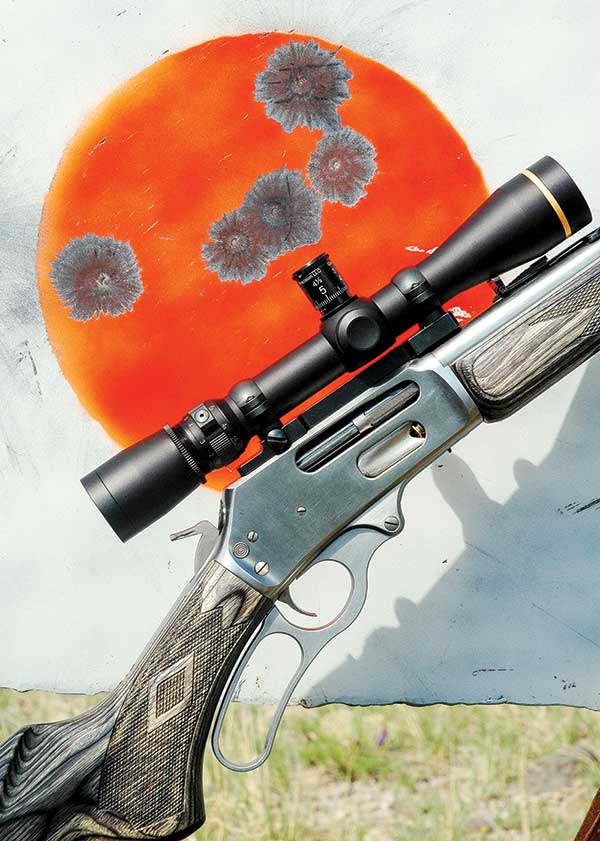

Winchester 94s in .30-30 have also plumped the record books. Those I’ve used, all built before accountants took Winchester hostage in 1964, fly to cheek faster than do Marlin 336s and seem to cycle more eagerly. As to fit, finish and reliability, these two models are neck-and-neck. Rifles of both models can be very accurate, halving the 3″ groups once commonly accepted. I’ve not torture-tested either but one Marlin proved its durability in a zero check on the prairie.

While I trotted out to change 200-yard paper, my pal fired up his Suburban to set steel plates at long range. He then ran over my shooting mat, crunching the Marlin’s receiver, lever and wrist into the earth. The butt-stock lay in pieces, lever askew. In a fit of equanimity, I counted to 10 (or was it 110?), then duct-taped the wrist. A vigorous tug on the lever freed the action, which then fed and ejected as if nothing had happened. Back on the mat, I prepared for gross sight adjustment. Instead, my shots centered the bullseye.

The Winner Is …

Yes, in my view, Marlin’s 336 deserves the wreath. But the Winchester 94 gets the popular vote. Credit timing. In 1860, while Benjamin Tyler Henry tinkered on a lever rifle Winchester peddled to the Union Army, John Marlin was tending parlor pistols. In 1883, as Winchester snared the brilliance of John M. Browning, Lewis L. Hepburn was still at Remington, yet to apply his genius with Marlin’s team.

Chronology matters too. As the Old West became legend, the wistful remembered Winchesters bringing it to heel before Marlin had a functioning lever-action.

Even the language gave the brand a boost. “Winchester” came off the tongue with the cadence of a galloping pony. Winchesters winning the West offered alliteration.

Films followed suit. Winchester ’73 blessed the box office. Could Jimmy Stewart and Shelley Winters have carried “Marlin ’81?”

Indeed, life is not fair.