Witness To Catastrophe

An Unusual Mosin-Nagant Rifle Finds Its Way Aboard

A Notorious German U-Boat In WWI

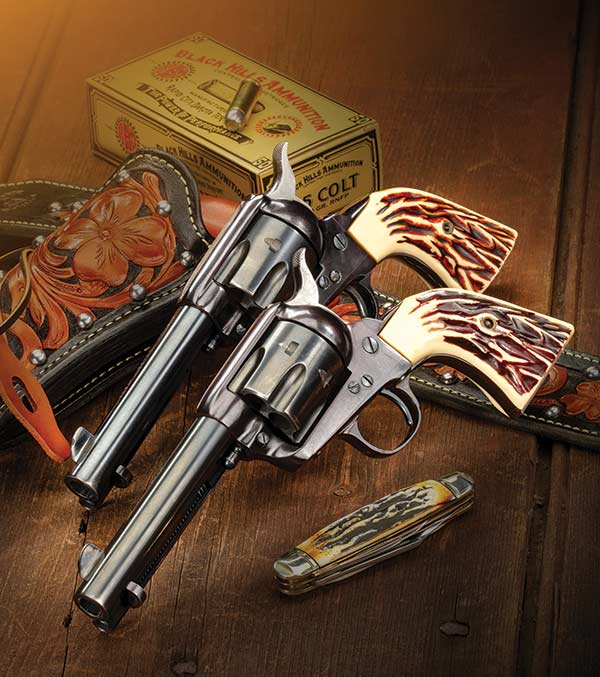

The alterations made to this Mosin-Nagant by Austria-Hungary for German service

are quite obvious. The original Russian top handguard has been removed, the original

fore-end and end-cap cut back to accommodate the addition of a Mauser-style end-cap

and bayonet lug, anchored in place by an H-band. These rifles remained chambered for the

Russian 7.62x54R cartridge and would have been issued with captured Russian ammunition

as long as it lasted. As stores of captured ammunition dwindled, both Germany and

Austria-Hungary manufactured 7.62x54R ammunition. A common version of the S88/98

ersatz bayonet may have been issued, too.

“A few minutes after the lifeboat first touched the water, every man jack in the group of surrounding boats took a flying leap into the sea. It was extraordinary to find myself in the space of a few minutes almost the only occupant of the boat. I turned around to see the reason for the exodus, and to my horror saw Britannic’s huge propellers churning and mincing up everything near them: men, boats and everything were just one ghastly whirl.”—Violet Jessop.

The mammoth 38-ton bronze propeller, still turning maximum rotations, in an attempt to beach the stricken ship, rose above the waterline as the HMHS Britannic began to list heavily bow down to starboard. Jessop, the British Red Cross stewardess, added “All round there were heartbreaking scenes of agony, poor limbs wrenched out as if some giant had torn them in his rage. The dead floated by so peacefully now, men coming up only to go down again for the last time, a look of frightful horror on their faces.” Jessop was rather unique in terms of her connection to the three most famous sister ships ever built: the Titanic, the Olympic and the Britannic. She was on board all three ships at their darkest hours, two of which sank to the ocean floor.

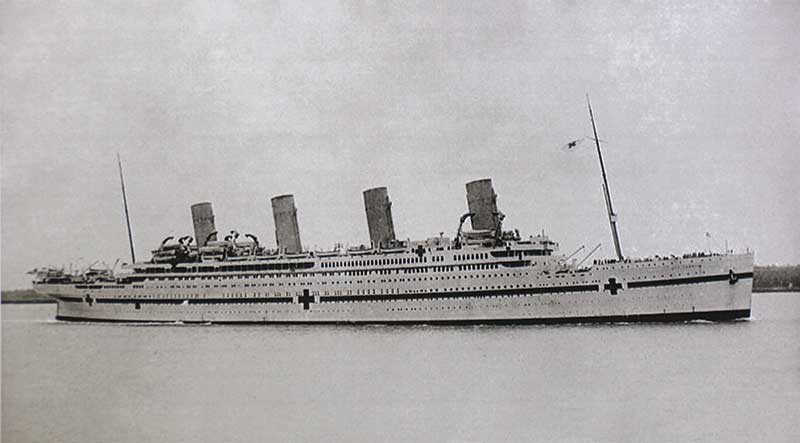

Violet Jessop was aboard the RMS Olympic when it collided with the British cruiser HMS Hawke off of the Isle of Wight in 1911. The crippled ocean liner limped back to port. A year later, Violet was a stewardess aboard RMS Titanic when it struck an iceberg and went to the bottom, taking 1,513 souls with her. Four years later, the plucky Irish lass was serving aboard the HMHS Britannic. Converted to a hospital ship during WWI, Britannic struck a mine and sank in the Kea Channel off Cape Sounion, the southern most tip of the Attica Peninsula of mainland Greece, November 21, 1916. This year marks the 100th Anniversary of her loss.

What has this sinking to do with GUNS Magazine? The connection lies with the Imperial Kaiserliche Marine having to play second fiddle to the Imperial German Army. At the outbreak of hostilities in August of 1914, German U-Boats were issued two MG-08 machine guns to detonate floating mines a safe distance from the submarine. However, as the unprecedented meat grinder of the trenches gobbled up men and material, standard-issue German small arms in naval use were recalled to serve in the trenches.

The weapons included the Gew 98 rifles and MG-08 machine guns. In their place, large numbers of captured Russian Mosin-Nagant M1891 Three-Line Rifles replaced weapons transferred to the army.

During the 1990’s, several large lots of these rifles were imported by Century Arms from the Balkans. Among them were a dozen unusual M1891’s, converted to mount Imperial German bayonets. Their forearms were cut back and a Gew 98-style end-cap with bayonet lug added and anchored in place with a typical Mauser-style “H” barrel band.

Still chambered for the Russian 7.62x54R cartridge, the sole reason for the alteration was to allow them to be issued with German bayonets. Based on period photos, the majority of Kaiserliche Marine units were issued captured Russian rifles with different variations of the all-metal S88/98 ersatz bayonets.

In examining several of these unusual rifles, the most obvious modifications were the removal of the original top handguard and the addition of the Mauser-style nose cap/bayonet lug, secured with an H-band, along with ersatz sling swivels. Rifles without the ersatz swivel were most likely issued with captured Russian dog-collar slings or, for naval use, without any sling at all.

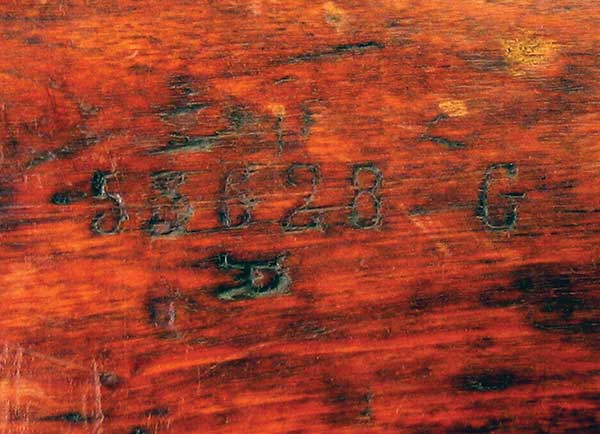

The rifle in this story was manufactured in Russia by Izhevsk in 1915. And part of its narrative, after it left Russia, is legible in surface features visible to the eye. The Romanov eagles had been scrubbed (a common practice in the Balkans after WWI). When I looked at the stock, the first obvious addition was an Austro-Hungarian serial number with a letter suffix stamped into the right side of the buttstock. Just below the serial number is a capital “R,” which indicates the rifle was inspected at Fegyver és Gépgyár, the government military arsenal better known as “FGGY”, located in Budapest, Hungary. The letter “R” was used as the arsenal’s small-parts inspection stamp. The next marking knocked my socks off. On the underside of the stock wrist, just below the triggerguard, was a rack marking. It clearly reads “U” over “73.” This rifle was one of two captured Russian M1891 Three-Line rifles issued to a German submarine, the U-73, a UE-1 Class Ocean Minelayer. The captured Russian rifles replaced the German small arms onboard the sub for the purpose of detonating floating mines with gunfire while on the surface.

While the H-band and end-cap with bayonet lug appear to be the same as the parts found on the Gew 98, a closer examination of the conversion reveals this H-band in particular is not identical to the H-bands produced for the standard-issue German rifle. The parade hook found on all German Gew 98’s is conspicuously absent. The left side of the H-band is stamped “R” over “73” in a vertical presentation rather than in the horizontal presentation commonly found.

This particular rifle is among the minority of M1891’s issued with a captured Russian dog-collar sling or perhaps no sling at all. The majority of the M1891 Gew 98 H-band adapted rifles (as they have come to be known among the collectors) had ersatz sling swivels added to their stocks to accommodate either the Austro-Hungarian M93 tongue-and-buckle slings or the buckle-and-button Mauser export-pattern slings.

During the 1990’s, several large lots of these rifles were imported by Century Arms from the Balkans. Among them were a dozen unusual M1891’s, converted to mount Imperial German bayonets. Their forearms were cut back and a Gew 98-style end-cap with bayonet lug added and anchored in place with a typical Mauser-style “H” barrel band.

Still chambered for the Russian 7.62x54R cartridge, the sole reason for the alteration was to allow them to be issued with German bayonets. Based on period photos, the majority of Kaiserliche Marine units were issued captured Russian rifles with different variations of the all-metal S88/98 ersatz bayonets.

In examining several of these unusual rifles, the most obvious modifications were the removal of the original top handguard and the addition of the Mauser-style nose cap/bayonet lug, secured with an H-band, along with ersatz sling swivels. Rifles without the ersatz swivel were most likely issued with captured Russian dog-collar slings or, for naval use, without any sling at all.

The rifle in this story was manufactured in Russia by Izhevsk in 1915. And part of its narrative, after it left Russia, is legible in surface features visible to the eye. The Romanov eagles had been scrubbed (a common practice in the Balkans after WWI). When I looked at the stock, the first obvious addition was an Austro-Hungarian serial number with a letter suffix stamped into the right side of the buttstock. Just below the serial number is a capital “R,” which indicates the rifle was inspected at Fegyver és Gépgyár, the government military arsenal better known as “FGGY”, located in Budapest, Hungary. The letter “R” was used as the arsenal’s small-parts inspection stamp. The next marking knocked my socks off. On the underside of the stock wrist, just below the triggerguard, was a rack marking. It clearly reads “U” over “73.” This rifle was one of two captured Russian M1891 Three-Line rifles issued to a German submarine, the U-73, a UE-1 Class Ocean Minelayer. The captured Russian rifles replaced the German small arms onboard the sub for the purpose of detonating floating mines with gunfire while on the surface.

I inspected this marking from every angle and in every conceivable form of lighting to ensure my imagination wasn’t running wild. The U-boat identification was bolstered when I noted another “R” stamped vertically above the number “73” on the side of the H-band. If a number is present on the H-band of a Mauser rifle manufactured with the H-band/bayonet lug combination, it is always stamped horizontally. This was another FGGY inspection mark.

Construction of U-73 was ordered on January 6, 1915, launched on June 16th and commissioned later that year on October 9th. In parallel, sometime during this same year, M1891 Three-Line Rifle No. 125248 was manufactured by the Russian arsenal at Izhevsk and quickly issued. Up to 28 percent of Russia’s soldiers went into battle with obsolete black-powder single-shot rifles or no rifles at all, so this M1891 would not have lingered long in the Russian supply chain.

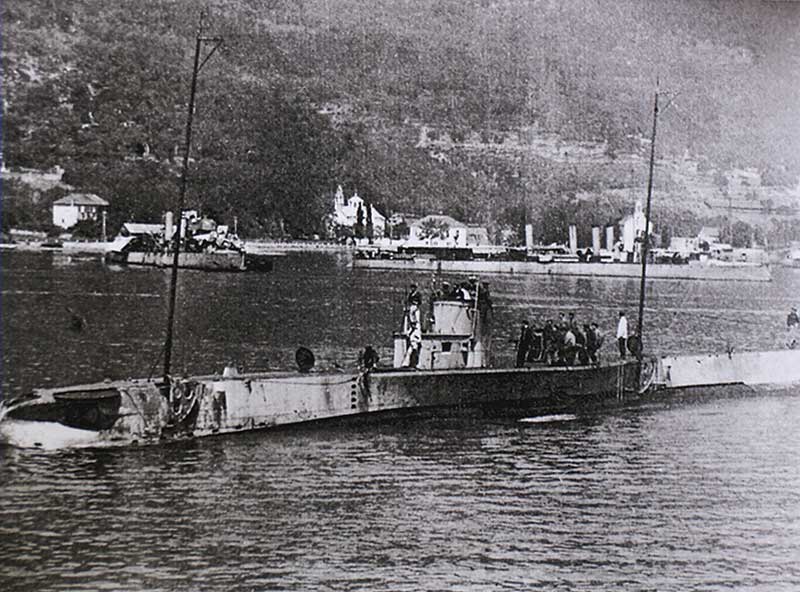

After launch, the U-73 joined the Kiel School and her shakedown cruise completed in February 1916. On April 1st, she left Heligoland Bight by way of the North Atlantic on her way to the Mediterranean, where she joined the Pola/Mittelmeer II Flotilla on April 30th. This U-Boat Flotilla operated from bases in Austro-Hungarian controlled territory at Pola and Cattaro on the Asiatic coast.

On the right side of the buttstock is both the Austro-Hungarian serial number “53628” with a letter “G” suffix, above the “R” denoting the rifle was inspected and reworked at Fegyver és Gépgyár, the Austro-Hungarian government military arsenal in Budapest, Hungary. The small-parts inspection mark of the Hungarian arsenal was a capital “R,” which appears on the stock of this particular rifle.

Too good to be true or just plain Irish dumb luck? John is pretty certain this captured Mosin-Nagant rifle was altered by the Austro-Hungarians, issued to German mine-laying sub U-73 and then abandoned to what was to become the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes after the U-73 had been scuttled at the close of WWI. The stock is marked on the fore-end “U-73.”

While the H-band and end-cap with bayonet lug appear to be the same as the

parts found on the Gew 98, a closer examination of the conversion reveals this

H-band in particular is not identical to the H-bands produced for the standard-issue

German rifle. The parade hook found on all German Gew 98’s is conspicuously

absent. The left side of the H-band is stamped “R” over “73” in a vertical presentation.

Whether or not she sailed with machine guns or rifles onboard is unknown, however, the fact they were later issued altered Russian rifles indicates the U-73 likely had rifles. At some point during the ensuing months, this M1891 went south from FGGY to Cattaro and eventually to U-73. The distance from Budapest to the U-73’s base at Cattaro is only 345 miles as the crow flies.

The conversion to the Gew 98-style H-band would also have been performed in one of the workshops at FGGY, as evidenced by the “R” stamped on the left side of the H-band. Regarding the availability of Mauser-style parts, Österreichischen Waffenfabriks-Gesellschaft (Steyr) was already manufacturing Mauser rifles, utilizing these parts in producing M1912 rifles and carbines for Mexico, Colombia and Chile. Large numbers of these rifles were commandeered by the K.u.K. from Steyr for issue to units of the Austro-Hungarian Army as the M14.

Kapitänleutnant Gustav Sieß was in command of the U-73 from the day it was commissioned on October 9, 1915, until May 21, 1917. Under his command, the UE-1 Class minelayer was responsible for sinking 16 Allied ships, including the 14,000-ton British battleship HMS Russell, with three additional vessels damaged. Kapitänleutnant Sieß was awarded the Pour le Mérite, the Knight’s Cross, often referred to as the “Blue Max.”

Between the hours of 8 and 9 a.m. on October 28, 1916, the U-73 laid “Minefield 32,” which had two rows of six anchored naval mines, across the Kea Channel off the southern tip of mainland Greece. Nestled in between Kea Island and Makronisos Island to the northeast of the Cape of Sounion, tactically this was an excellent location to lay mines. The Allies were heavily engaged in fighting the Austro-Hungarians and Bulgarians on the Salonika Front in Macedonia in an attempt to aid of the embattled Serbs.

The Allied naval base on the island of Mudros, originally established to support the ill-fated Gallipoli Campaign, remained the center of all Allied naval activity in support of operations in the Eastern Mediterranean.

On November 21 at 8:12 a.m., HMHS Britannic struck a mine. At 48,758 tons she was the largest of the three Olympic Class vessels and the largest ship sunk by any means during the entire course of the war. Based on the lessons learned from the loss of the RMS Titanic, a number of alterations were made in the design of the Britannic to correct the faults believed to have resulted in the loss of her famous sister ship.

Despite all of the changes made in the design and equipment of the Britannic, the ship sank in a mere 55 minutes, while the Titanic remained afloat for 2 hours and 40 minutes after colliding with the iceberg. The reasons for this are still debated. Some survivors reported a secondary explosion perhaps the result of illegally stored munitions, despite her serving as a hospital ship, while others attribute the second explosion to the ignition of coal dust.

Factors contributing to the rapid flooding of too many compartments may be attributed to Murphy’s Law. There was a shift-change underway in the boiler rooms when the ship struck the mine, which may have resulted in one or more of the crucial watertight doors being left open. With six watertight compartments flooded, the Britannic was pushed to the very limits of her design. It seems the last straw came in the form of the otherwise harmless annoyance of the stuffy/stagnant air below deck on the liners of the day. Against regulations, a large number of portholes had been opened to improve ventilation of the hospital wards located on the lower decks. As the ship listed to starboard, water poured in through the open portholes sealing the fate of Britannic.

HMHS (His Majesty’s Hospital Ship) Britannic, the sister ship of the RMS Titanic

and the RMS Olympic, never served as the luxurious ocean liner she was intended

to be. Shortly after November 13, 1915, the RMS Britannic was requisitioned by the

Royal Navy to serve as a hospital ship to help evacuate soldiers wounded in the

disastrous Gallipoli Campaign. No sooner had the ship been equipped as a floating

hospital than the campaign came to an end. Attention in the Eastern Mediterranean

shifted to the Salonika Front in Macedonia, where the Allies attempted to prevent the

collapse of Serbia following the concerted effort by Germany, Austria-Hungary and

Bulgaria to knock them out. The ship was painted white with a long green band painted

along the side punctuated by three large red crosses located towards the bow, amidships

and near the stern. Photo: Allan C. Green, public domain

The U-73, a UE-1 Class Ocean Minelayer, is pictured returning to Cattaro, one of

several Adriatic coast bases hosting U-boats of the German Pola/Mittelmeer II Flotilla

in territory controlled during the majority of the war by Austro-Hungarian forces. From

the commissioning of the U-73 on October 9th, 1915 until he surrendered command of

the U-73 on May 21st, 1917, Kapitänleutnant Gustav Sieß was one of the most successful

U-boat commanders of WWI. By the end of the Great War he ranked number six among

the most successful U-boat captains having accounted for 56 ships sunk or captured

with an additional 10 ships damaged. Photo: Internationales Maritimes Museum Hamburg,

used with permission.

While only 35 of Britannic’s 46 lifeboats were successfully launched and remained afloat, due to the ship’s immediate list to starboard, the loss of life was primarily limited to the 30 men killed when their boats were sucked into the propeller. Britannic was returning to Mudros from Southampton after having carried a full shipload of wounded back to England. As a result, there were only 1,095 people aboard. Capable of carrying 3,309 wounded, the scope of the disaster would have been much greater had Britannic struck the mine outbound for England.

As WWI drew to a close, the U-73 was deemed unfit for the return journey to Germany. All usable equipment and the small arms were removed before the submarine was scuttled at Cattaro on October 30th, 1918. At some point, the Russian rifles issued to the Kaiserliche Marine were either abandoned, captured or surrendered to Allied troops. The rifles must have remained in storage in some out-of-the way place in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes to escape being reconfigured as standard-issue M1891 Three-Line Rifles.

Violet Jessop survived the disasters of the RMS Olympic, Titanic and HMHS Britannic. Despite being forced to evacuate two of the three largest sister ships ever built, Jessop continued to serve at sea with the White Star Line, the Red Star Line and finally the Royal Mail Line. She died in 1971 at the age of 83.