The .300 Savage

Why Not Choose Our First .300?

A swatch of color reined me in. Over the next hour several elk winked in and out of timber below but the slope was rock-rolling steep. I dared not move. Then, an aspen shivered. The cows eased by it, passed my K4’s crosswire in a gap not much wider than a Harley, then vanished.

The aspen kept shaking. Suddenly a long antler slammed it down.

I descended a few more yards, sliding on my hip. One more cow glided through the gap, only her top half visible. The bull denied me even a chance — a blink in the slot. I almost cried.

Things Change

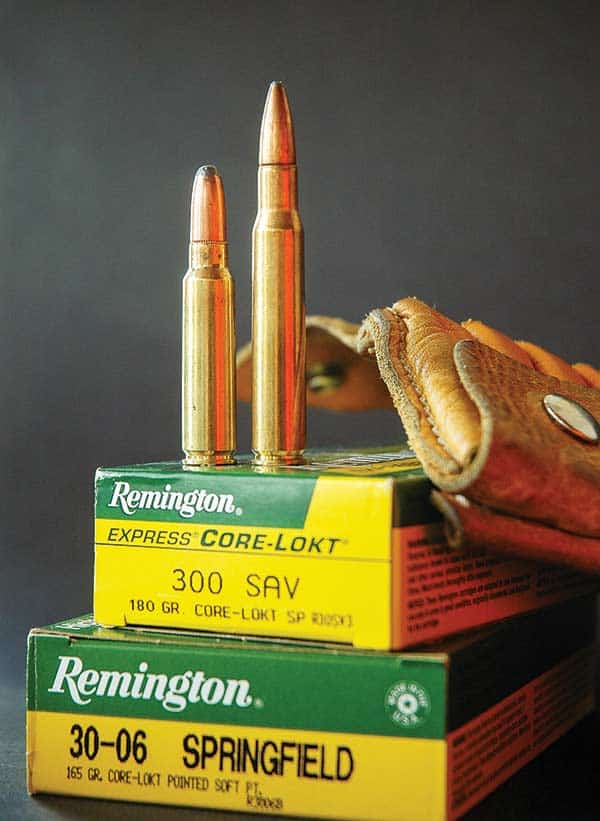

Suddenly, charitably, elk emerged in a grassy slip between hogbacks. Bald heads. Then — antlers! The bull stopped behind a fir. I was out of “almosts.” As soon as his chest cleared the tree, I fired. A 180-grain round-nose Remington Core-Lokt trundled out the muzzle at 2,370 fps. The bull took one more step and fell on his nose.

It was my nod last autumn to the .300 Savage’s 100th birthday. No fire-breather, this stubby, light-recoiling .30 is quietly efficient, a deadly round with a storied past. I’d used it earlier on deer, pronghorns and caribou. To be honest, though, I hadn’t expected the big bull to collapse instantly. Not that I’d bought into the myth only magnums upend elk. Indeed, a survey just before WWII showed the .300 Savage was a popular elk cartridge, in ballistic step with the .30-40 Krag if not the .30-06 and clearly superior to the ubiquitous .30 W.C.F (.30-30). In Savage’s Model 99 rifle, it would topple North America’s toughest game for nearly eight decades.

Roots

The Model 99 and our first .300 appeared concurrently 28 years after Arthur W. Savage, then 35, invented the Savage No. 1, a hammerless lever-action cycled with the little finger. A spool magazine held eight cartridges. A musket-style stock cradled a 29″ barrel. Savage submitted his repeater to ordnance trials but it lost to the Krag-Jorgensen bolt gun, which became the official U.S. service arm in 1892.

However, convinced of the merits of his rifle, Savage reconfigured it for sportsmen. He reduced magazine capacity to five for a trimmer profile and opened the lever for three fingers. Patents in 1893 described a prototype rifle in .32-20. On April 5, 1894, he formed the Savage Repeating Arms Company in Utica, New York. The next year, Marlin Firearms Company supplied tooling and built the first Model 1895 Savage rifles, bored for the new .303 Savage. Its .308-diameter 190-grain bullets flew as fast as lighter bullets from early .30 W.C.F. loads and so hit harder. A hunter in British Columbia claimed 18 kills using a box of 20 cartridges, with two grizzlies in the count.

The 1895 was catalogued with 20″, 26″ and 30″ barrels in .303 only. About 6,000 rifles were built between 1895 and 1899, when Savage modified the action. The new Model 1899 appeared in .30 W.C.F. a year later. So similar was the new rifle to its predecessor for $5 Savage would fit the earlier version with a new bolt, hammer, sear and hammer indicator. In 1903 the .25-35, .32-40 and .38-55 filled out the cartridge roster. All were dropped in 1919.

Savage’s first catalog, circa 1900, listed the Model 1899 for $20. They appeared with barrels of 20″ to 28″. Barrel contours had letter designations — A for round, B for octagonal, C for half-octagonal. The 1899-F saddle-ring carbine was a hit. The CD Deluxe and H Featherweight arrived in 1905.

Advantages

The 1895’s mechanism was almost fully enclosed. In lock-up, its bolt abutted the steel web at the rear of the forged receiver so it protected the shooter better than did other lever guns in the event of case failure. Still, loading was easy through the ejection port. As iron sights gave way to scopes, the 1895’s side ejection became a notable asset. A coil mainspring — more durable than leaf springs then common — was first-ever on a commercial lever gun.

A through-bolt held butt-stock to receiver more securely than did wood screws in tang extensions. The receiver protected the magazine. Unlike tubes, this spool didn’t contact the barrel, so had no effect on accuracy. With cartridge weight between the hands, balance was unaffected by cartridge count, shown in a window. Savage’s magazine permitted use of pointed bullets.

Rifle sales could turn on testimonials, like the 1901 letter from Teddy Roosevelt hailing his Model 1899 as “the handsomest and best turned out rifle I have ever had.” Given T.R.’s affinity for 1886 and 1895 Winchesters, such praise got a warm reception. The company also touted the ’99’s accuracy, gracing its 1903 catalog with a 10-shot, 100-yard group 1-5/16″ across.

The Model 99 Arrives

In 1920 Savage re-introduced its Model 1899 as the Model 99. The action was little changed, but this “new” rifle chambered the truly new .300 cartridge, in barrels rifled 1-in-12 (later, 1-in-10). By some accounts, the .300 Savage was to wring .30-06 vigor from the short lever mechanism yet because of its stubby 0.221″ neck, the 1.871″ Savage case fell well shy of matching the capacity of the ’06’s 2.494″ hull.

Hunters didn’t seem to mind the 250 fps gap. In the M99, the .300 Savage sold to the walls and remained the rifle’s most potent chambering for 30 years. It also blessed other rifles. I have a Remington 81 autoloader and a 760 pump in .300 Savage. It appeared briefly in Winchester’s Model 70 bolt-action. Around 1950, the U.S. armed forces considered the .300 Savage as a stand-in for the .30-06 but its 30-degree shoulder balked in some self-loading mechanisms. A slightly bigger case, with a 20-degree shoulder, evolved as the T-65. This became the .308 in 1952, the 7.62 NATO in ’55.

Arthur Savage didn’t live to see a 99 in .308. By the Battle of Britain, he’d prospected for oil, run a tire company, farmed California citrus and died in 1941.

Forerunner

The .300 Savage preceded, by five years, the .300 H&H and was 25 years ahead of Weatherby’s .300. While these and subsequent magnums outmuscle it, the .300 Savage punches above its weight — and the M99 is a sturdy, reliable rifle.

Once, I borrowed a 99 in Canada’s far north to hunt caribou. Spotting a bedded bull a mile across featureless tundra, I hiked in a great arc to sneak up behind it, closing to iron-sight range. The bull died without rising, the best barren-ground specimen I’ll ever take.

I tried to buy the rifle. “Sorry,” said its owner. “It goes to my Inuit guide.” I cringed. This pristine Savage would soon have a salt-water finish, its steel patched by rust, its walnut scarred by ice, sled dog claws and canoe gunwales.

Ninety-nines in .300 Savage have served me on the desert too. Bellying across Wyoming sand with many pauses, I inched within 100 steps of a fine pronghorn and shot it through the heart. The same rifle crawled with me through sage after a mule deer I’d watched bed on a distant ridge. Making like a lizard, I couldn’t see more than a few feet ahead when an antler tip came clear. Eye to the aperture sight, I lifted a foot and let it fall to earth. Again. The buck rose. My soft point struck him at 20 steps.

Yes, I adore the Model 99 — and in truth can’t say I’ve ever needed more cartridge for hunting on this continent than our first .300.