Long-Range Sixguns

It Can Be Done

Whatever the reason, U.S. Army Scout Matthew Holden had made a serious error resulting in serious trouble. The day had been beautiful and Buck wanted to run, so Matt had allowed himself to get too far ahead of the troop. He must have been several miles forward when he first saw them. That small band of Apache warriors was not only pursuing him, they’d cut off his retreat as they moved in between the lone scout and the troops.

Now it was up to his big buckskin horse and him to outrun his pursuers. Buck had been called on many times to carry Matt to safety; however, the years had taken their toll on both Matt and Buck. Nevertheless, Buck was giving it his all. As Matt looked over a shoulder to see how far back the half dozen or so Apaches were, he felt that first ominous sign.

Buck still had the heart but his body was starting to fail him. Matt knew this as he felt Buck stumble ever so slightly. Even his heart was not enough. There was another stumble and then down he went. Matt was able to leap from the saddle and avoid being pinned.

However, when Buck went down, he fell on the scabbard holding Matt’s old ’66 carbine. It wasn’t Army issue but Matt preferred its repeating and quickshooting capabilities to the issued singleshot Trapdoors. Now he had neither. Perhaps Buck would save him one more time as Matt’s only hope was to use Buck’s fallen body as cover as he tried to keep the Apache warriors at a distance until the troops caught up with him. All he had was his 7.5″ .45 Colt Single Action Army. Could he do it?

Elmer Says Yes

Writing in Sixguns (1955) Elmer Keith says, “During the Indian campaigns on the plains, quite a few cavalry officers who had learned to shoot a sixgun during the Civil War became very expert at long-range revolver shooting. With their horses shot out from under them, they were able to keep enemies out at long rifle range and completely out of bowshot with the old 7.5″ Peacemaker.

A good revolver shot with a long-barrel gun and accurate heavy ammunition can, and frequently did, make it hot for enemy horsemen out to 400 or 500 yards. When shooting over dry, dusty plains or over water where the strike of the bullet could be located, they could hold accordingly and soon walked their shots onto the target.”

This wasn’t the first time Keith had written about long-range sixguns. Two of his early articles in American Riflemen in September 1928 and April 1929, told of a visit from Harold Croft and the 700-yard shooting they did on Keith’s little cattle ranch in Durkee, Oregon. Keith would follow these articles with one in November 1930 showing pictures of custom Flattopped Colt Single Actions and Bisley Models looking much like the current Ruger Blackhawks and Bisley Blackhawks.

That article was probably read and preserved by a teenager by the name of Bill Ruger. In an article written in May 1939, Keith mentions earlier proponents of long-range shooting such as Chauncey Thomas, E.A. Price and Ashley Haines, all well-established writers and editors when Keith was a young man.

More Precedents

We can go back a lot further, in fact all the way back to the first true Colt sixgun, the Walker of 1847. Sam Walker said this .44 caliber percussion revolver was good on man or beast out to 200 yards. Moving up to more “modern” times we find a little book called The Long Shooters And The Origin Of 300 Yards Revolver Shooting by W.B. Altsheter. This book, published in 1912, talks of long-range revolver shooting using .38 Special and .44 Special six-guns. Even before the advent of the modern Magnum, John Henry Fitzgerald, Colt’s “Fitz” mentions long-range shooting in his 1930 book, Shooting, and Smith & Wesson’s Major D.B. Wesson in his book Burning Powder (1932) talks of long-range shooting with the then-new Smith & Wesson .38/44 Outdoorsman.

Another of the more extensive sections on long-range shooting with a sixgun is found in Ed McGivern’s 1938 book, Fast and Fancy Revolver Shooting. All of these men definitely believed accurate long-range shooting was more than possible with a revolver, it was also practical.

In Practice

One of the most well-known and also most maligned examples of long-range shooting was of Elmer Keith killing an Idaho mule deer at 600 yards. Keith was a long-time booster of long-range revolver shooting, how-ever he never, ever advocated long-range shooting of game animals with a revolver.

The True Story

The truth of the story is simply the deer had been wounded by a rifle shooter who was now out of ammunition and a crippled deer would soon be gone over the top of the ridge to die a lingering death. Keith took the prone position, fired four times, and hit the deer twice at ranges between 500 and 600 yards. His fourth shot put the deer down for good. Keith was using a very early Smith & Wesson 6.5″ .44 Magnum.

Earlier Keith told of taking a deer in 1954 with his 4″ .44 Special. This time he was fishing and hobbling along on a sprained ankle and had the opportunity to shoot a doe at 125 yards. He missed and the deer took off running. His next three shots also missed, however he connected on shot number five at around 150 yards. Since he was unable to hunt the steep hills that year, Keith said, “I can only conclude the good Lord was looking out after my meat supply.” He also said, “This was longer range than a short sixgun should ever be used on big game, but I wanted the venison badly.”

The sport of long-range silhouetting certainly proved all of these men correct in their assessment of the use of revolvers for long-range shooting. Several shooters have managed to shoot perfect scores taking down all 40 targets, 10 each at 50, 100, 150 and 200 meters with a revolver. I never achieved perfection but did come close, shooting a score of 38 with my 10.5″ Ruger .357 Maximum leaving one turkey and one ram standing. That remains, and will always remain, a local club record as the club has disbanded.

Can Holden Hold ’Em?

Back to Matt Holden and his predicament. I decided to find out for myself if Sam Walker and Keith were correct in that it was possible someone caught in a situation such as Matt’s could actually survive. To test the theory, I did everything short of shooting from behind a downed horse. The sixgun used was an original circa 1881 7.5″ Colt Single Action Army chambered in .45 Colt. Instead of modern square sights with a square rear notch matched up with an equally square front sight, this old sixgun has a very shallow “V” rear sight and a very thin tapered front sight.

With black-powder loads, the only loads that should be used in an old sixgun such as this one, I had earlier ascertained it would keep five shots in 1″ at 50′. I used the same loads, a 255-grain conical bullet over 40 grains of black powder in old-style balloon-head brass, as this was the original loading of the .45 Colt. The military soon backed this off to 30 grains as most soldiers found the recoil more than they could adequately handle.

A standard man silhouette target was set up at 50, 100 and 200 yards. Shooting two-handed and using a solid rest — as Matt would have done— and two cylinders full for each target, I discovered three things.

First, at 50 yards that old sixgun and I could be counted on to deliver head-shots. If our targets were at this range and standing still they had no chance.

Second, at 100 yards, we could consistently place all our shots in the body. Once again, the adversary would not have a chance.

Third, things changed considerably at 200 yards. Sighting at this distance with those 125-year-old sights and my not-quite-as-old eyes made it very diffi-cult. I never did hit the outlined body of the target silhouette. However, I did hit the paper several times. The shots that missed the paper were so close that as the old six-gunner said, I could keep him pinned down until someone showed up that could really shoot. Keith and Walker were definitely correct and Matthew Holden, Scout, United States Army would survive.

Rules? What Rules?

Long-range shooting, like plinking, has no rules, no required stances, no maximum sight radius and no caliber restrictions. Even though I prefer big-bore calibers, .44 and up, as the bigger and heavier the bullet the easier it is to see it hit — and longer barrels, 7.5″ to 10.5″ for shooting at long distances —my best shot ever was made up with a 4″ .22 Single-Six.

Any safe place is fine for long-range shooting, however, the best shooting conditions are over-dry barren ground where the dust kicked up helps us dial in the range. A friend’s ranch has a large vertical rock face about 300 yards from the house. It’s most enjoyable to pick out spots and shoot long range with a 10″ Ruger .22 semiautomatic as even the strike of those little .22 bullets can be seen.

Witnesses

Fortunately for my credibility, two well-known fellows in the industry witnessed the above-mentioned best-shot-I-ever-made-with-a-sixgun. Rod Herrett of Herrett Stocks and gun-writer Clair Rees, now with Barnes Bullets, and I were varmint hunting outside of Jarbidge, Nevada, and had done all the damage we wanted to do with scope-sighted rifles and pistols. So out came the iron-sighted .22 pis-tols. Rod had a K-22, Clair a .22 semiautomatic, and I had my little .22 Single-Six custom round-butted with the barrel trimmed back to 4″ by ’smith Andy Horvath.

I had asked the fellows to spot for me by training their binoculars on a small rock on a dirt bank at the end of the field we were overlooking. My first shot was slightly low, the second shot hit the rock, and I opined if one of those little ground squirrels popped out I could take it.

It wasn’t more than a few minutes later a squirrel popped up. I lined up the sights, slowly squeezed the trigger and down he went. The range finder read 181 yards. I’ll be the first to admit I couldn’t do this every shot, or even with most of my shots. I can’t guarantee how often I could make such a shot, however I have noticed the more I shoot long range the better my chances of making such a hit.

Long Shots

My two longest game shots were made under the best possible condi-tions. The longest revolver shot I ever made at a big game animal was 125 yards on a Texas whitetail buck. The revolver was a Freedom Arms Model 83 7.5″ .44 Magnum with a 2X Leupold scope, a revolver that had been shot extensively during many whitetail hunts and always loaded with the same ammunition, Black Hills 240-grain jacketed hollowpoint. I knew the sixgun, I knew the ammunition and I knew what I was capable of doing when shooting from a solid rest. I had a solid rest, the whitetail was standing perfectly broadside pre-senting me with my kind of shot and the results were perfect. One shot and one deer who never moved except straight down.

I’m willing to stretch the range quite a bit when using a single-shot pistol, such as Thompson/Center’s Contender. My SSK T/C has a 14″ 6.5 JDJ, a 2.5-7X Simmons scope and is sighted to hit dead-on at 250 yards using a 120-grain Speer JSP at 2,400 fps. My powder of choice for this combination is Accurate Arms No. 2520. If I have a solid rest with the 6.5, I’m confident out to 300 yards. The longest shot made was another one-shot kill on an antelope at 250 yards. Notice both times I had scope-sighted handguns, a solid rest and my shots were still well under the 600-yard range of Keith’s mule deer. When using iron sights I prefer to stay under 100 yards — actually, the closer the better.

Backstop Blues

We have no restrictions placed upon us when long-range shooting with iron-sighted sixguns at inanimate objects. Whether we miss or hit has no great consequences. There’s no prize if we hit and no animal to suffer needlessly if we have a near miss. If so inclined we can count only the hits and forget the misses if we also learn in the process. It’s very unlikely we will ever have to hold off a half-dozen pursuers while waiting for help to come but it is mighty reassuring to know if we had to we could.

Rocks and old tree stumps make excellent targets. However, any safe target is acceptable, with a large safe backstop being absolutely necessary. It should go without saying — signs, utility poles, etc., are totally out of the question. As our country becomes more and more urbanized with housing developments packed closer and closer together, it is imperative we know where our bullets are going to finally come to rest.

Many of the barren areas I used for long-range shooting 35 years ago are now places of habitation. I’m not the only one noticing this as such solitary creatures as cougars have found their winter grounds suddenly paved over with large rectangular-shaped boxes in great abundance.

Penetration

Several years ago my pistol packin’ preacher friend, Jim Taylor, and I were shooting above the Gray’s River in Wyoming. Our targets were abandoned log cabins con-structed of logs 6″ to 8″ in diameter. Jim and I were both using 7.5″ Rugers, his a first-year .45 Colt Blackhawk and mine an even older .44 Magnum Flattop. Both of us were also using 300-grain bul-lets, his at 1,200 fps, mine slightly over 1,300 fps. Sitting down on the hillside with a right knee drawn up and used as a rest neither one of us had any prob-lems hitting those cabins. Even at 700 yards they were fairly large targets. What is significant is those bullets had enough energy left to penetrate the front wall and exit the back. Once heavyweight bullets get moving they’re very difficult to stop.

Another time in Wyoming we set up a 2′ square section of bright-orange-painted metal, propped up against some sagebrush on the side of the hill. The distance was 800 yards this time and it looked much like a pinpoint out there in the desert. This time shooting the same .45 Colt load in a 4.75″ Freedom Arms I was able to hit that target several times before my box of 100 rounds was gone. Normally, shooting long range, we don’t hold over the target, but rather raised the front sight in the rear notch with the target perched on top of the front sight, just as Elmer Keith had always taught. However, this range was so extreme I ran out of sight long before I ever got to the target and found myself aiming at a piece of sagebrush well above the target. Precision shooting?No way! Fun shooting? Absolutely!

My preferred sixgun set up for shooting long range is a 7.5″ to 10.5″ barreled big-bore revolver with large, square, black sights. For my eyes, the choice is a black front post without a white outline rear sight. An undercut post is even better but they wreak havoc with the interior of leather holsters. I once approached a downed deer to finish him off and found I could not get my sixgun with its undercut post out of my shoulder holster without help.

Ramp-style front sights tend to get lost, at least for me, in bright sunlight and the same is true of colored inserts. The standard old Smith & Wesson red ramp front sight is wonderful on a cloudy day, however to my eyes it loses its square shape and fades out in bright sunlight.

Position

The best shooting position? Purely subjective. One of the most practical is standing, almost squarely, facing the target with the shooting side leg slightly forward and using two hands with the offhand used to support the shooting hand. I like to exert a slight push-pull action with the shooting and supporting hand. It’s the easiest position to assume, the quickest and also the most comfortable.

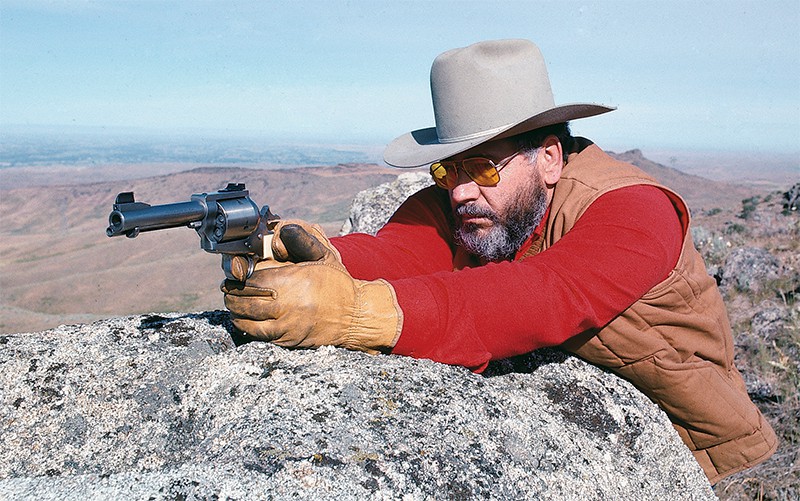

If a backrest is available it can be used to excellent advantage from the sitting position with both elbows resting inside drawn-up knees and once again, using two hands. The downside is the fact pants, or worse, can be burned by the hot gases exiting from the gap between barrel and cylinder.

Prone

The worst position for me is prone. I have no neck, rather my head just sits upon my shoulders and there’s no way I can hold my head back enough to shoot prone whether with a handgun or rifle.

There are three ways to shoot one-handed. The classic bull’s-eye stance with the shooting arm extended straight, the body slightly turned with the foot on the shooting arm side forward and the offhand at the side tucked in a pants pocket or with the thumb tucked in the belt, is one of the toughest ways to hit long range. Of course it makes it most gratifying when we connect.

Long-range silhouetters still use the Creedmore position. This is assumed by lying on your back, placing the off-side arm under the back of the head, the shooting-side knee drawn up with the shooting hand resting against the outside of the knee and the elbow on the ground. Some shooters are able to place their left-hand on the ground behind their head, however I always had to forcibly hold my head up due to the no-neck situa-tion. If any amount of shooting is to be done, this position requires some sort of a blast shield to protect the leg from the hot gases coming from the barrel-cylinder gap of a revolver.

Once, unbeknownst to me, I had my soft leather blast shield slip during a match as I fired a .357 Magnum sixgun through the stages. I was so intent on shooting I didn’t realize what was hap-pening. When I finished I had a large hole in the side of my pants with blood oozing from my leg. The biggest concern was neither the pants nor the blood but rather the possibility of lead particles entering my leg. A solid, immovable blast shield is absolutely essential for this position.

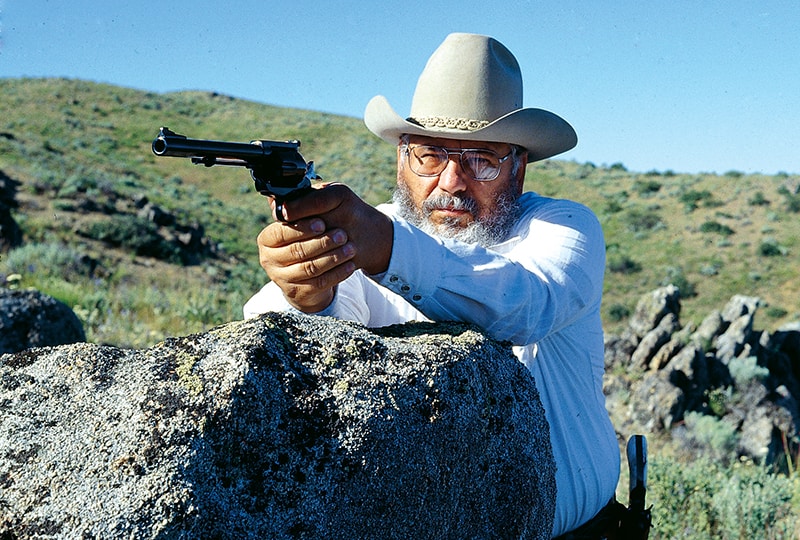

The best one-handed position for me and perhaps the best position period is the classic Keith position. This is shot from sitting, leaning back on the off-hand elbow, drawing in the knee of the shooting side, and the shooting hand placed on that knee for support. With a little practice this position becomes very stable and also capable of allowing us to shoot very accurately.

Practice

With a little practice, a long-range sixgunner soon finds it fairly easy to outshoot the average rifle shooter. Several years ago I purchased a 4″ Smith & Wesson .44 Magnum. I planned on sending it to Mag-na-port for porting and refinishing with a Mag-na-loy finish, which would give it a stainless steel look. Round butting and general tune-up were also in the cards. But, before spending the money, I wanted to first shoot it at long-range. With this in mind I ventured to the Black’s Creek Shooting Range where I could bust rocks on a hillside 250 yards from the shooting area.

As I arrived, I found only two other shooters who were intent on trying to hit the same rocks and having very little success. “If you’ll spot for me I’ll try to hit that rock,” says I. “Where’s your rifle,” says one of the unsuccessful rifle shooters? When I told them my rifle was the short-barreled .44 Magnum, I could see they wanted to laugh but thought better of it. My first shot was just under the rock; the second shot hit the rock. They both packed up and left. I guess they never heard of anything such as long-range shooting with a sixgun.

Get More Revolver Content Every Week!

Sign up for the Wheelgun Wednesday newsletter here: