Keep It Simple

Fixed Sights On Handguns Are Sturdy And Dependable Once Sighted In

My attitude about fixed sight handguns being good choices came shortly after becoming a Montana resident. Often I drove my pickup or an old ’51 jeep off the pavement. And I put hundreds of miles a horseback in the mountains. It seemed my target-sighted handguns were forever becoming un-sighted-in by being banged on vehicle doors or from many imaginative ways horses found to rough them up. That’s not all. I would hang a perfectly sighted handgun up for the winter and come spring often it didn’t hit where aimed. Reality taught me appreciation for fixed-sight handguns.

However, there is an oft-repeated but untrue saying in shooting lore that goes, “Once sighted in, fixed sight handguns are always sighted in.” Not necessarily. Truth is, once sighted in with a very specific load they will likely always be sighted in for the same shooter. Change powder type or amount, bullet alloy, shape, diameter or lubricant or even primer type and point-of-impact can shift from point-of-aim. Change grips or firing stance say from 1-handed to 2-handed and point of impact can again shift. Try this: sight in a handgun from 2-hand, sandbag rest and then stand up and shoot it with 1 hand. It may hit at the same point of aim. It may not.

Weight Woes

Changing bullet weight is a special offender. In regards to handguns only, lighter, faster bullets hit lower on target than heavier, slower ones. It’s a matter of physics: the instant a bullet begins to move recoil starts the handgun’s muzzle moving upwards. Heavier bullets recoil more hence they impact higher. They are also usually in the barrel longer than lighter bullets that can accentuate the process.

Firearms manufacturers take this into account by computing the height of a front sight by the most likely bullet weight with which a handgun will be fired. To demonstrate this to others I use my Colt New Frontier with 7-1/2-inch barrel. By aiming it at a mark while someone stands to the side it is quite obvious to them the muzzle is pointing slightly downward.

While I do appreciate fixed sights now, looking back on how they were in the past causes me to shake my head in wonder. As in: I wonder what the manufacturers were thinking? In fact let’s go back to one of Colt’s most popular cap-and-ball revolvers of the mid-1800s. Collectors today call it the Model 1851 Navy .36. Its front sight is a tiny brass bead and the rear is a V-notch in the hammer. There is no practical manner by which they can be moved for sighting in purposes. Literally, what you see is what you get. No wonder many 19th century revolvers exist with dovetailed front sights put on by after-market gunsmiths. Then both elevation and windage changes could be determined by a competent shooter. That’s the way I built my Model 1861 converted to fire .38 Colt metallic cartridges.

Evolution

As revolver designs developed guns with top straps over cylinders became the norm. Into those top straps were milled grooves to serve as rear sights. Early on the sight-picture was still a V-notch, evolving into a U-notch and finally into a square notch. This didn’t happen quickly. In the 1920s Colt was still giving the SAA a V-notch rear. My earliest fixed-sight Smith & Wesson is a Hand Ejector, 2nd Model .44 Special shipped in 1929. It has a square-notch rear sight.

In some cases front sights actually improved more quickly. I have a 1904 vintage Colt SAA .38-40 whose front sight is so thin (0.055 inch) it can almost cut you. However, in the early 1900s revolver sights began to thicken. At the same time Colt was still putting V-notch rear sights on the SAA after they began to use 0.100-inch front blades. That made for a miserable sight picture. Like I said, “What were they thinking?”

It seems by the 1920s (and for about 50 years) fixed front sights on handguns were about 0.100 inch. That S&W Hand Ejector, 2nd Model .44 Special has a 0.100-inch front blade as does a 1946 vintage S&W Military & Police .38 Special. It seems after about 50 years front sights thickened even more. Two of my 1970s S&W Military & Police .38 Specials have fronts 0.125-inch wide as is the front sight on my newest S&W revolver. That’s a Model 22 .45 ACP from 2006.

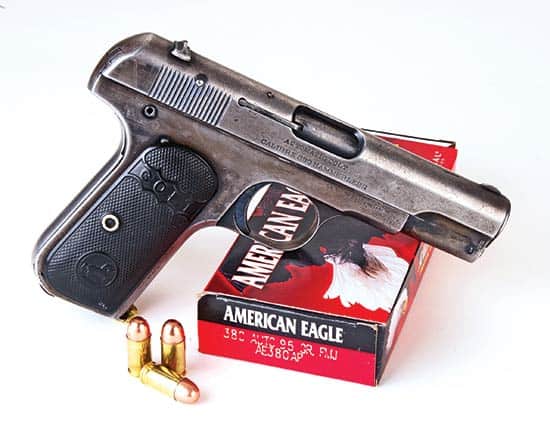

As John M. Browning’s semi-autos became widespread circa early 20th century, they received a U-notched bar of steel for a rear sight. It was dovetailed to the semi-auto’s slide and so at least moveable for windage. A tiny nub of a front sight was staked to the barrel. I have two World War I vintage Colt Model 1911’s. Both have front sights 0.057-inch thick. According to US Army requirements Model 1911’s were supposedly sighted for 50 yards. Good luck with that!

By WWII Model 1911A1 sights had thickened to 0.080 inch with the rear notch becoming square at the bottom. The most recently manufactured Colt 1911 I have is one of the high-polished stainless steel .38 Supers made in the 1990s. Its serial number’s prefix is “ELCEN.” Supposedly these are from an overrun made especially for south of the border sales. Interestingly, its sights are normal blued steel with white dots. The front one is 0.130-inch wide and rear is about twice the height of military 1911 rear sights. Even with aged eyes I have no problem at all with this sight arrangement. Why such sights were not used on all Colt 1911’s from the beginning goes right back to, “What were they thinking?”

Corrections

Once in my early years as a gun’riter an editor told me “holding off with a handgun is no big deal.” Well, it is to real shooters so I never sent the numbskull another manuscript. By the way, the late Charles Askins once wrote that while a Border Patrolman he took pliers and bent the sights of the outfits’ newly received Colt New Service .38 Specials. It seemed none of them were sighted in for their duty load as received from the factory.

In the mid-1980s I took his words to heart one afternoon when a new Colt SAA .44-40 was hitting left of center. So I took the pliers from my pickup’s tool box and bent its front sight to the left. It then hit perfectly on—pliers tracks and all. Although I have used this method more than once I do not recommend it anymore. One correspondent let me know his SAA’s sight came off instead of bending. (Bad Duke!) It’s far better to have a single action’s barrel tweaked for windage in its frame by someone with a vice, barrel blocks and experience.

Another correspondent whined it bothered him to have his expensive gun’s front sight leaning oh-so slightly left. My response is it bothers me to not hit what I am shooting at. Besides you only see the top of the sight when aiming.

That brings us to the point of adjusting elevation. Hitting low is good. A sight can be filed to bring impact up. But even here I say it’s best to have someone with plenty of file experience do the work. Hitting high is bad; it is hard to raise a sight. I actually squeezed one in a large, smooth-jawed vice one time. Then I had it filed back into shape when sighting in. It did get very thin however.

I will be the first to admit some fixed sight handguns are so far off that getting them sighted in would be a monumental task. I once bought an S&W Heavy-Duty .38-44 (.38 Special on their .44-size frame). At 25 yards its point of impact was about 9 inches from point of aim out at about 7 o’clock. No way was I ever going to get that thing hitting on so it was sold.

Upon getting deeply involved in WWII firearms and purchasing many handguns of that vintage, one factor about the German 9mm Luger and P38 was quickly evident. They had front sights dovetailed to their barrels. Windage was corrected by drifting them laterally. As for elevation, these sights were made in a variety of heights so replacements are fairly easy to obtain. This was exactly the case with my P38. A couple of differing heights were ordered off the Internet and one brought point of impact dead on. Those German designers were thinking!