Snubbies — It's Not Just You

They ARE hard to shoot!

Back in the day, there were quite a few colorful nicknames for the short-barreled revolver. Some called them “card-table guns,” suggesting their effectiveness rapidly diminished once the target was more than about 10 feet away. Others called them “belly guns,” hinting they’d be best used if pressed against the stomach of a would-be assailant and the trigger worked as rapidly as possible. In either case, there’s a clear implication if you’re looking for accuracy out of a snubbie, you’re barking up the wrong tree.

The internet, however, offers pretty compelling evidence to the contrary. Hie thee to YouTube, and you can watch the late Bob Munden going three-for-three in terms of hitting a 200-yard gong with a J-Frame. Renowned shooter Jerry Miculek accomplishes the same 200-yard shot with his snubbie, but he holds it upside down and pulls the trigger with his pinky.

As with most things in life, the truth lies somewhere between the two extremes. Is the snub-nosed revolver mechanically accurate enough to make long-distance hits? Absolutely. Will the layperson be able to do so? Not without some serious practice!

It helps to remember the snubbie, however “cute” or unassuming it may be, is a purpose-driven tool. Yes, it can offer outsized firepower in a compact size but it only does so as a result of very noticeable and significant tradeoffs to shootability. However, I offer this — if we understand why these guns are so hard to wrangle, we emerge with some great lessons of how to make them do our bidding.

Elevated Recoil

We’d do well to first think of a snubbie as a scaled-down gun shooting a full-sized cartridge. Here there’s no getting around the laws of physics — force equals mass times acceleration. If the force of the discharged round remains identical, a small gun is going to accelerate into your hand far more vigorously than a large one.

This is true as guns have continued to get lighter and more powerful. To wit, the advances of firearms science over the last 70-odd years have given us 12-oz. revolvers that can withstand the pressures of .357 Magnum. It’s too bad our hands haven’t adapted as rapidly! Reading a few shooting impressions around the internet, the overwhelming consensus is shooting an ultra-lightweight snubbie with full-bore ammo is an exercise in masochism. One person described it as feeling like a bomb is going off in his hand. Most agree shooting a Desert Eagle in .50AE is a far more pleasurable experience!

Still, I’d argue shooting even a steel-framed snubbie with most .38 special ammo isn’t exactly pleasurable. It’s not uncommon for shooters to get smacked around, poked, nipped, or otherwise abraded by these guns. Recoil has long been the enemy of good shooting and when the trigger of your gun is functioning as a literal pain switch, flinching is all but inevitable.

Squished Internal Geometry

Once again, the shrunk-down revolver has the same job to do as its bigger brothers, which in turn has more implications on user-friendliness than most people realize.

For one thing, the tiny hammers of snubbies have a reduced arc of travel than their full-sized brethren, along with less mass. As a result, snubbies rely on extremely stiff mainsprings in order to supply their hammers with the energy required to punch primers. Additionally, the rebound spring is responsible for resetting the trigger and all of the internal lockwork back into place, though in comparison to a bigger gun it has less travel distance to do so. Once again, a tiny but extremely stiff spring is the design solution — and both of these springs must be compressed by your trigger finger.

Trigger pulls of about 14 to 16 lbs. are not uncommon on a snubbie — this is about 40% to 50% heavier than a well-broken-in DA on a full-sized gun, based on my own personal revolver inventory. With this additional resistance, it’s all the more difficult to execute the “perfect” trigger pull, which is to say pressing slowly and evenly to the rear. Many shooters will simply muscle it and yank through the stiffness, pulling the shot off center. Some shooters with compromised hand strength may not be able to pull the trigger at all!

Most experts will also note the “feel” of a snubbie is often different than a larger revolver. Not only is spring weight a reason for this, but the type of spring has something to do with the phenomenon. Many Colts and S&W revolvers utilize flat mainsprings as opposed to the coil springs of most snubbies. With a flat spring, the load is typically compressed in a more linear nature, whereas a coil spring typically needs a little more initial pressure to get moving, and tends to “stack” more perceptibly at the end of the trigger pull.

Other Quirks

Beyond all of the above, the little things can be awkward to steer. While the industry has made definite strides when it comes to designing usable grips, for most snubbies there’s just not a whole lot to hold onto. As a result, it’s often difficult to find a comfortable, natural grip easily replicated from draw to draw.

I find especially with smaller snubbies my index finger has to get at the trigger via a pronounced downward angle. If I want to get at the trigger less obliquely, I typically end up with my pinky finger underneath the tiny butt of the grip. It works, but it doesn’t feel great!

Put these grip issues together in combination with the reduced mass, and it basically means any flinch or mash is going to be amplified — it’s all-the-more easy to win a pushing contest with the snubbie than with any other gun. Target shooters typically like a little more barrel out front to allow a handgun to “hang on target,” so to speak. You don’t get much here.

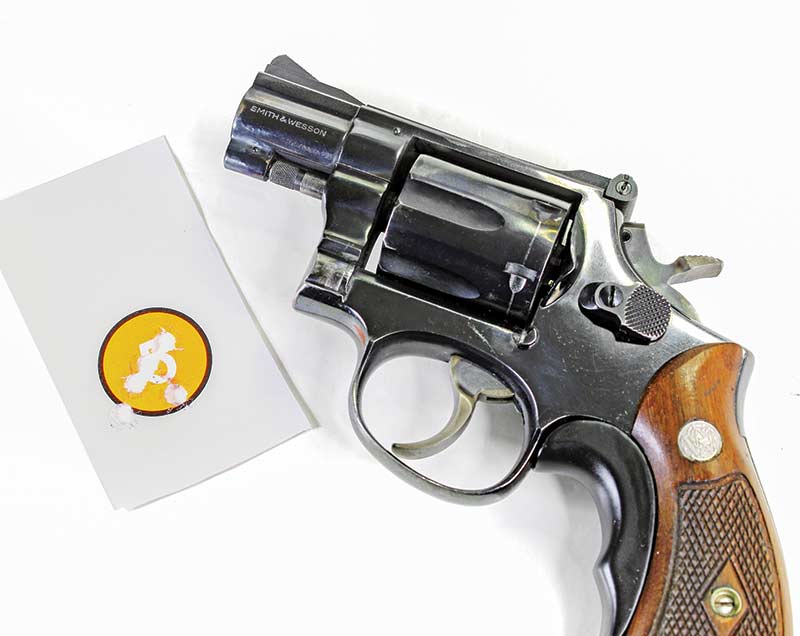

Oddly enough, sight radius doesn’t tend to be the major indicator of why it’s hard to shoot one of these guns well. True, this allows for less “slop” in one’s sight picture and necessitates more careful attention to the amount of light on both sides of the front sight as seen through the rear notch. If you’re shooting for tight groups at a distance, this does indeed matter. For the majority of users, however, trigger control will explain 90% of why a seemingly well-aligned shot missed.

Solving The Problems

First and foremost, I’m perpetually amazed at the amount of people who’ll keep shooting a gun after it has drawn blood. That’s not a fun proposition for me. The snub-nosed revolver in a defensive caliber requires the shooter to exercise a little more care when it comes to hand protection. I recommend just about any shooting glove with some extra leather or padding at the web of the hand. It will absolutely make a difference.

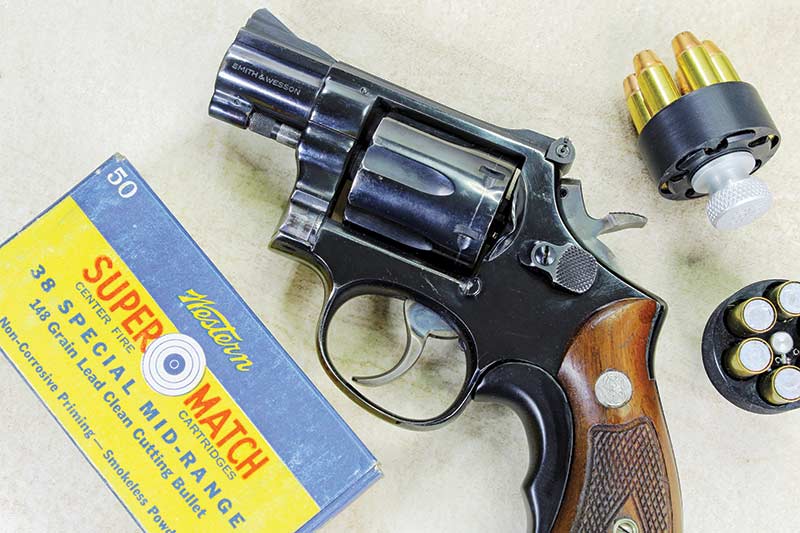

Also, consider what gets stuffed into the charge holes. Even if it says .357 Magnum on the barrel, it doesn’t mean that’s what you have to shoot! Rather than magnum or +P defensive ammo, snubby practice is a lot easier and fun with full wadcutter ammo or lighter-loaded “cowboy” rounds in the 125-grain range. Both can be tough to find in rural areas, but are absolutely worth one’s time to source. Take pain off the table and I guarantee you’ll be amazed how just these two tips alone make your snubby begin to sing.

Beyond this, dry-fire practice is more essential with the snub-nosed revolver than any other platform. Mastering the tight, stiff DA is non-negotiable. I find manipulating the trigger with what our own Massad Ayoob refers to as “the power crease” of the index trigger works best for me. Depending on your gun and hand size, this technique may result in a shot being pulled very slightly to the left or right, but rarely will it result in an outright miss on a reasonable target within 50 feet.

Lastly, and if you can, it’s worth addressing the ergonomic issues inherent to the snubbie. Even a set of larger practice grips for some of the most common brands can allow one to have a better range day and shoot closer to the snub-nosed gun’s potential. Additionally, grip adapters from Tyler, BK, or Pachmayr do wonders in filling in the “sinus” behind the trigger guard, resulting in what I guarantee will be a better feel over itty-bitty panel grips.

Even after all of these modifications, you might still find your snubbie isn’t easy to shoot — certainly, as a tool, it has clear limitations. Limitations I would add, which often make it just about the worst choice for a new or elderly shooter. These guns aren’t for novices, precisely because they’re small. However, I have no doubt you’ll find the snub-nosed revolver a little more accurate and versatile than you may have thought. They can be mastered, and the journey can even be fun!