The .260 Remington

Once a wildcat, this 6.5mm, based

on the .308 Winchester, has proven

itself on the range and in the field

If somebody surveyed opinions of the .260 Remington, they’d be as diverse as subway passengers in New York City. Many respondents would check the box marked “don’t care,” but other shooters think the .260 is the greatest centerfire cartridge ever introduced.

The .260 is one of six of commercial cartridges based on the .308 Winchester case, with the same body and shoulder angle, only 0.03-inch difference in overall length. Half have been successful—the .243 Winchester, 7mm-08 Remington and, of course, the .308 itself. The less popular half are the .260, .338 Federal and .358 Winchester.

The .308 appeared in 1952, as the commercial version of the new 7.62×51 NATO round. We don’t know who initially necked it down to use 6.5mm bullets, but among the first was Ken Waters, a part-time gun writer from upstate New York, who designed his version in 1956, calling it the .263 Express. Like many Eastern hunters back then, Waters wasn’t enamored with 1955’s .243 Winchester, which appeared in Field & Stream, due to the shooting columnist, Warren Page.

The US was then in the midst of its post-World War II economic boom, and shooters wanted newer, zippier cartridges. Page was an avid wildcatter, who convinced many shooters .243-caliber bullets were far more effective than the .25-caliber bullets of the “old” .250-3000 Savage and .257 Roberts. This wasn’t strictly true—but Page handloaded his 6mm wildcats to much higher pressures, resulting in much higher velocities.

Unfortunately, only one American “premium” bullet existed back then—the Nosler Partition—and it needed to be handloaded. The cup-and-core bullets used in factory .243 ammo sometimes came apart at the typical close ranges of Eastern deer hunting, the reason many “woods” hunters preferred heavier bullets at moderate velocities. Ken Waters was one of those hunters.

The 6.5mm (0.264-inch) bullet diameter originated in early smokeless military cartridges, using 155- to 160-grain roundnose bullets, eventually morphing into 139-grain (9-gram) spitzers, much heavier than any 6mm or .25-caliber bullets. So Waters came up with the .263 Express—but instead of necking down .308 cases, he necked up .243’s.

The result was a round with only slightly less powder capacity than the 6.5×55 “Swedish Mauser,” so the ballistics were nothing new. But the .263 would fit into the magazines of several new short-action rifles, including Winchester’s Model 88 lever-action, Model 100 semi-auto and Remington’s Model 722 bolt.

However, in the 1950’s most Americans thought 6.5mm cartridges were weird. If they wanted to shoot bullets heavier than 100 grains, they mostly used good old American rounds like the .270 and .30-30 Winchester.

Long Range

Eventually, some folks “discovered” 6.5mm bullets had higher ballistic coefficients than other calibers in their weight-range, due to target bullets made for the 6.5×55. The 139- to 142-grain spitzers made for the 6.5×55 turned out to be excellent for long-range shooting of any kind, drifting less in the wind than faster but shorter bullets from .25 and .27 caliber rifles, resulting in less recoil than the .30 caliber rounds Americans traditionally used for long-range target shooting.

Well-known competitor David Tubb started winning matches with rifles chambered for the 6.5/.308 wildcat, and silhouette shooters found 6.5 bullets retained enough energy to knock over iron rams at 500 meters. Among the new 6.5/.308 enthusiasts was a gun writer who, like Warren Page, had a monthly column in a large-circulation magazine, Outdoor Life. Jim Carmichel called his version the 6.5 Panther, and helped persuade Remington to introduce the .260 in 1997.

This was about when affordable, hand-held laser rangefinders became available to American shooters, resulting in scope changes that also extended practical range. Many shooters started using 6.5mm cartridges for long-range hunting, finding the .260 a good choice.

I acquired my first .260 in 2001, a medium-heavy custom rifle built on a short Remington 700 action with a 1:8-inch twist Hart barrel. I mounted an early “tactical” scope with a multi-point reticle and extra-tall adjustment turrets, mostly using the rifle for long-range varmints, though it took one deer. (Exactly why tall turrets were tactically necessary was never clear, although marketing might have had something to do with it.) Far more premium bullets appeared, making 6.5mm bullets practical for game larger than deer.

As the 6.5 trend accelerated, various companies brought out target bullets with even higher ballistic coefficients, due to elongated boattails and ogives. Some proved a little too long for the .260 in the standard short magazine length of 2.8 inches. The curve of the ogive ended upside down inside the short neck, so it didn’t hold the bullet firmly. Various solutions were tried, including longer magazines, but wildcatters soon developed 6.5’s short enough for long-ogive bullets to fit inside short magazines. Eventually factories did too, including the 6.5 Lapua and 6.5 Creedmoor, both with the 30-degree shoulders considered more accurate than the 20-degree shoulders of .308-based rounds. But the .260 still remains popular enough for Lapua to continue offering its excellent brass for the cartridge.

Hunter’s Round

Hard-core .260 fans are often hunters who prize the cartridge’s “versatility,” saying their handloads can essentially reproduce the ballistics of the .243 Winchester, .25-06 Remington and 7mm-08 Remington. This sounds marvelous, but while such versatility was valued before World War II, when many hunters couldn’t justify owning more than one centerfire rifle, post-war Americans could afford far more. In fact, I have yet to run into a .260 fanatic who owns only one centerfire rifle or even one .260, weakening the versatility argument.

But that doesn’t mean the .260 isn’t a fine hunting round, especially in a lightweight rifle, thanks in part to newer premium bullets with higher ballistic coefficients. I recently started handloading for a Tikka T3 Lite in .260 Remington, part of a special run of 100 rifles ordered by Whittaker Guns in Kentucky. (If you ever end up in the Owensboro area, be sure to stop in, since it’s one of the finest gun stores I’ve encountered in 50 years of firearms shopping. (Be forewarned: My single visit so far cost more than expected.)

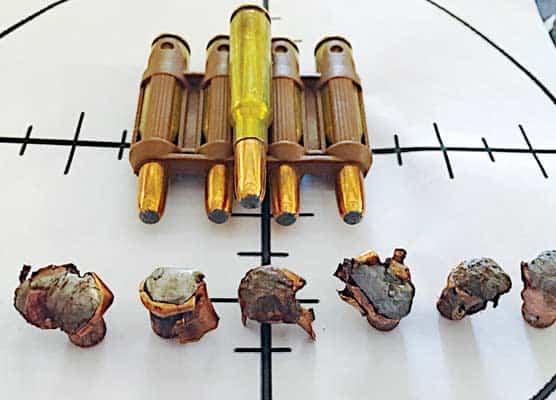

Tikkas have a reputation for fine accuracy and triggers, right out of the box. This one only weighs 6 pounds, 14 ounces with a 3.5-10×40 Leupold in Tikka factory mounts, and the trigger breaks very crisply at a consistent 3-1/4 pounds. (The trigger can be easily adjusted lighter, but to me the pull seems perfect for a cold-weather hunting rifle.) The loads listed do cover any sort of American hunting from varmints to elk, but it should be noted that the 100-grain Ballistic Tip is one of Nosler’s Hunting bullets, and of course Barnes TTSX’s are also fine big-game bullets.

But for most hunting with smaller 6.5’s, I prefer bullets in the 125- to 130-grain range, since they provide an excellent combination of trajectory, minimal wind-drift and power. But there’s certainly nothing wrong with 140’s, especially when after game like elk and moose. I wouldn’t hesitate to hunt either with a .260 and, for those who prefer even heavier bullets, Norma offers their fine bonded-core 156-grain Oryx. Scandinavians have been using the 6.5×55 on moose for a very long time, and the .260 provides exactly the same performance.

Half of John Barsness’s dozen books are on firearms and shooting. His latest is The Hunter’s Guide to Handloading Smokeless Rifle Cartridges, published in the fall of 2015 by Deep Creek Press.