Pocket Pistol Shootout!

A 100-year-old 1908 Bayard goes mano a mano with a

Kel-Tec P-3AT for the lightweight .380 ACP title

I recently tested a Kel-Tec P-3AT .380 ACP (three-A-T, get it?) and was impressed with how far pocket pistols have come. I liked the pistol so much I got one of my own. Being historically minded, I began pondering how my new double action, polymer frame, wonder-of-modern technology might compare to its old school, all-steel, single action, blowback ancestors. This sort of idle speculation is the type of thing writers make a living on.

In the first decade of the 20th century, when autoloading pistols gained widespread commercial acceptance, pocket-sized pistols became big business. Even in the 19th century, small pocket revolvers were the backbone of personal protection. The new pocket autoloaders offered more firepower in a more compact package. Small in size and caliber, they were rarely longer than 5″ (indeed in Europe the “10-centimeter” pistols were tiny pocket guns) and usually in .22 LR, .25 ACP or .32 ACP. The strong market encouraged technological innovations and experimentation, and many excellent designs emerged, mostly out of Europe.

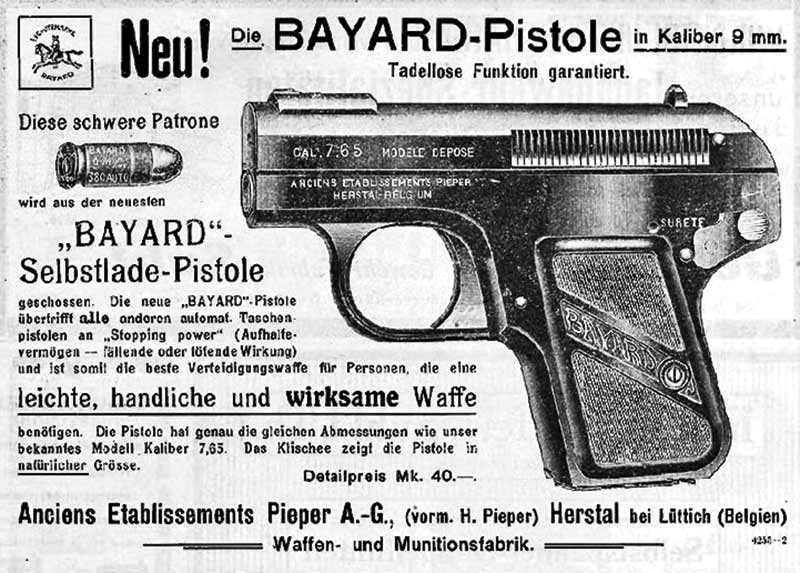

The Model 1908 Bayard was one of the most impressive of those early autos. Made by Anciens Etablissements Pieper (A.E.P.), in Herstal, Belgium, on their own patents, it stood out from its peers for three reasons. First, it was offered in .380 ACP, a rarity for any pocket pistol. The barrel was also mounted low on the frame to reduce muzzle flip, like the Model 1900 Browning. Finally, it used a unique buffer system to cushion recoil. It was marketed throughout the world as the smallest and softest shooting .380 ACP pocket pistol. Made from 1911 to 1923, it sold well. This was cutting-edge design in its day, which is why I selected it for my old-school test piece.

Modern Mode

Nearly 100 years after the Bayard first appeared, Kel-Tec CNC Inc. of Cocoa, Fla., reimagined the traditional pocket pistol, took it into the polymer era and revived the concept in the American market. This is no small feat, as pocket pistols were slowly slipping from collective memory since the Gun Control Act of 1968 curtailed their importation. Domestic manufacturers emerged and produced some high quality pocket pistols in the intervening years, but Kel-Tec’s approach resulted in an extremely thin, concealable gun with about a 50 percent weight reduction. That was the biggest change in pocket pistols since the double action.

Rounding up both guns, I tested the pistols for accuracy and function with traditional 95-gr. FMJ ball ammunition and four popular brands of self-defense hollow points: Speer 90-gr. GDHP, Gold Dot Duty Ammunition, Hornady 90-gr. FTX Critical Defense, Winchester Defend 95-gr. JHP and Federal Premium 90-gr. Hydra-Shok JHP. Firing was done at 15 yards from the bench.

I kept those tiny grips encased in a two-hand hold, my hands in turn solidly rested on a sandbag. I set the chronograph to record velocity at the muzzle so I could compare it to factory claims. All the velocities recorded were 200 to 300 fps lower than advertised.

The 1908 Bayard’s magazine, incidentally, holds five compared to the Kel-Tec P-3AT’s six. Advantage: Kel-Tec.

Triggers

The Bayard had a fairly heavy trigger pull for a single-action auto, perhaps around 8 lbs., but it was smooth and broke cleanly with a short reset. It traveled only 1/8″ before firing. By contrast, the Kel-Tec’s double action pull is a bit lighter but travels about 7/8″ before firing, with a comparatively long reset time. Even though the pull is quite smooth, there’s a lot more time and motion involved to throw off your aim. The extremely thin grip made it hard for me to center the pad of my fingertip on the trigger. In precision shooting, the Bayard’s single-action trigger has the advantage. This would probably be the case with any single-action pocket pistol. But for carry, I’d lean toward the DA trigger of the Kel-Tec.

Sights

Both pistols feature sights designed for fast acquisition, though the Kel-Tec’s are also snag-free. The Bayard sights are traditional but minimized, comparable in actual size to those on a military Mauser of this era and using a protected blade front sight and “V” rear notch.

Sight alignment on the Kel-Tec relies upon the eye’s ability to cap a flat rear-sight plane with a triangular front sight making a perfect triangle with the tapered top edges of the slide. The flaw with this system is if the muzzle is too high, the sight

picture still looks like a perfect triangle. It requires some concentration but it works. The precision shooting advantage lay with the Bayard.

Recoil

Felt recoil and muzzle flip is noticeably greater with the skinny, 10 oz. Kel-Tec. The steel Bayard’s bare frame is 15 oz. and almost as thick as the polymer gun. Add Bakelite grip panels for added girth and an internal buffer, and the recoil on the Bayard is much easier to control. It was actually much lighter than I expected. Their advertising it as being soft-shooting actually turned out to be the case.

The Bayard’s patented recoil attenuating buffer assembly was unique at the time and rarely used in any handgun since. The S&W Model 61 Escort of the early 1970’s was essentially the 1908 Bayard reincarnated in .22 LR, but for many reasons (mostly due to poor construction) it died a fast death in the marketplace. The Bayard’s buffer took the form of a tube mounted on the frame above the grip. When fired, the rearward motion of the slide compresses the recoil spring and guide rod into the buffer tube and they bottom out against a spring-backed piston at the rear to cushion the recoil impulse. I tried to compress the piston by hand with a flat-head punch and got barely 1/16″ of movement out of it, so I’m not convinced it was still functioning on my test pistol.

Perhaps more important than the buffer in minimizing felt recoil and muzzle flip, is the Bayard’s short, low-mounted barrel and general ergonomics. The hammer is mounted low in the frame behind the grip, giving the pistol a slight (10 degrees or so) downward point. In an effort to objectively quantify the difference in muzzle flip between the Bayard and Kel-Tec, I summoned up long suppressed memories of high school physics class, and built a simple test device using a 3/16″ wood dowel crossbar, tensioned thread and a ruler.

To test, I placed the top of the slide in contact with the bottom of the crossbar at a fixed point and squeezed off a round. The rising muzzle carried the bar up with it. I could determine the height the

crossbar rose by lifting it until all the slack in the previously tensioned string was taken up. The upward force was described in millimeters as determined by the highest point the end of the crossbar rose against the vertically oriented ruler perpendicular to the swinging end of the crossbar. The results were consistent and showed the Bayard had about half the muzzle flip of the lighter Kel-Tec. It actually worked! My test device and the gun’s design.

The 2-3/16″ barreled Bayard moved the crossbar up a mere 44 mm on average. The 2-3/4″ barrel Kel-Tec raised it 85mm. I cannot say exactly what factor weight, barrel length, the presence or lack of a buffer and the height of the barrel above the gripping hand played in the result. But the effects of this difference were quite apparent in rapid fire. The felt recoil and muzzle flip was less with the Bayard.

Function

The Bayard had one failure to feed out of 100 rounds fired. The edge of the open cavity on the 90-gr. Hydra-Shok JHP hung up on the unpolished feed ramp. Twice the last round fired stove-piped. It was amazing to me how a gun designed for ball ammo digested modern hollow points with near perfection. Its success is due to the generous feed ramp cut into the frame. It’s the full width of the magazine and about 20 percent wider than that on the Kel-Tec. The latter’s feed ramp is integral with the barrel and probably shouldn’t be so aggressively enlarged, since it’s part of the camming mechanism locking and unlocking the action.

My Kel-Tec initially had trouble feeding any ammo dependably, including ball! Reliability was restored by carefully polishing the feed ramp to a mirror shine with 400-grit sandpaper on a dowel. Feeding problems reappeared in rapid fire because I repeatedly — accidently — released the magazine while shooting. The place where my thumb naturally wanted to rest on the frame turned out to be right on top of the Kel-Tec’s rather prominent magazine release button. For me, this is a serious problem in a self-defense gun. I intend to cut the button down nearly flush with the frame.

In the grand scheme of things, it’s much better for a magazine to stay in than it is for it to fall out. Even compared to other pocket autos of the era, the Bayard magazine is quite challenging to get out. It’s released with the somewhat awkward but extremely effective traditional catch mounted on the very bottom rear of the grip frame. These catches are meant to prevent the accidental release of the magazine and they meet the design criteria admirably.

However, the Bayard magazine lacks the typical metal lip protruding from the front you would normally pull on. I needed to turn the pistol around in my right hand so the slide was in my palm and use my thumb to pull back the catch. While pulling the catch open, I used my fingernails to get under the magazine side tabs to draw it out. This is not the kind of operation I can see anyone doing under stress, but then, why would you? By the time you need to change magazines, you should be somewhere else where there isn’t a gunfight

going on.

Safety

Once the Bayard’s slide is racked to chamber a round, the pistol is cocked and ready to fire. Unlike the Kel-Tec, it has a manual safety. Located on the left rear of the frame, it’s impractical to use while the pistol is held in a shooting grip. Since the safety physically holds the sear in position against the hammer, it would be highly unlikely to discharge if dropped. The opposite is true with the safety off. I suspect most users with any sense at all carried the Bayard (or any other single-action pocket pistol) with the safety engaged. It was surely detrimental to speed, but to do otherwise invites accidental discharge in the pocket. And in all honesty, it’s probably best to carry it with the chamber empty. And probably better not to carry it at all!

The Kel-Tec relies on its long double-action trigger pull for safety. Racking the slide only chambers a round and moves the hammer to a sort of half-cock/pre-cock position. It does not fully cock the pistol. The pistol can’t fire if dropped because it has an internal hammer block that can only be moved by pulling the trigger. To fire, the hammer must be drawn back to its release point with a full pull of the trigger. The Kel-Tec is meant to be carried with a loaded chamber. Like a revolver, it’s ready for instant use and is just as safe to carry in the pocket. I’d vote the safety category is handily won by Kel-Tec

Accuracy

The Bayard, thanks to its conventional sights, heavier weight and single-action trigger, proved more accurate than the Kel-Tec P-3AT in slow fire. The Bayard’s recoil-diminishing design also made it superior in rapid-fire point-shooting without sights, though to a slightly lesser degree. The average 5-shot group size (of all ammunition types) in slow-aimed fire was 1.6″, with groups centered about 1.8″ above the point of aim. The Kel-Tec shot average groups of 2.9″ centered about 1″ below the point of aim.

In two-hand hold, rapid-fire point-shooting, there was less difference in practical accuracy. I shot at a man’s T-shirt stretched over a cardboard form, pointing for the center of the chest and firing as fast as I could without trying to use the sights in any way. The groups shot from the Bayard averaged 6.75″. The Kel-Tec’s groups were more spread out, mainly vertically. I estimate in the 8″ to 10″ range. Because I had difficulty with magazine release induced jams, I had a lot of incomplete groups on the target so I considered them in the aggregate. If I sorted out the mag issue with the Kel-Tec, I’d say both guns would work for the assigned role, but the Bayard does seem to be easier to shoot accurately.

Durability

A.E.P. had a reputation for quality firearms and it shows in the Bayard’s beautiful workmanship. It was a complex pistol to make and probably not quite durable enough for the .380 ACP caliber. For example, the slide is both guided and held in the frame by two short rectangular pieces of rail riveted on the inner left side of the frame. That’s not much for a .380 ACP! My 100-year-old test gun showed signs of metal bending on the front face of the slide, the tail of the front sight/recoil spring retainer behind it and the rear of the back guide rail.

The lighter Kel-Tec P-3AT is actually sturdier in design. Its slide is more stable, being retained by double guide rails on the left and right of the frame. However, those rails are made of aluminum, and I think if they are not kept clean and lubricated, the friction of the hard steel slide against them could accelerate wear. The Kel-Tec has fewer parts than the Bayard (37 vs. 45) and its engineering is eloquently simple. Fewer moving parts means there’s less to break or wear out. New technology is better.

There are practical considerations to carrying vintage guns. Finding spare parts can quickly become akin to a Medieval quest. Fortunately, magazines and replacement grips are not a problem. Triple K Manufacturing (triplek.com) in San Diego, Calif., makes replacement magazines for the Bayard and about 1,000 other pistols. They also make historic reproduction grips; a set of which I put on the test pistol before the cracked and fragile Bakelite originals crumbled away.

Conclusions?

Though separated by a century-wide technological chasm, the 1908 Bayard and Kel-Tec P-3AT are cut from the same cloth. Their .380 ACP caliber puts them on the top rung of pocket-pistol power and their extremely small size makes them easy to carry and conceal. If you don’t imagine yourself in a quick-draw confrontation where trying to disengage the Bayard’s awkwardly placed safety will cost you your life, then the Bayard is the better pistol for self defense in terms of accuracy and speed.

If you need to draw and shoot without warning, the Kel-Tec’s double action will get your first shot off faster. To get this first shot — and subsequent ones — to hit the target is going to require practice to master the long double-action trigger pull. This would be the case with any double action. The Kel-Tec’s other main advantage is it’s extremely light and thin. It doesn’t sag or bulge your pocket as much as your typical one-pound steel gun. It’s the most easily carried pocket pistol ever made.

A pistol that’s easy to carry is a pistol you’re likely to carry. So it seems modern wins out here for several reasons. Modern design, modern materials, better ergonomics and the fact it’s, well … not 100 years old.

Bayard Self-Loading Pocket Pistol (1908 Bayard) .380 ACP

Manufacturer: Anciens Etablissements Pieper (A.E.P.), Herstal, Belgium

Weight Loaded/Empty: 17.6 oz/15.9 oz

Material: Steel

Magazine Capacity: 5 shots

Safety: External manual lever

Height: 3.67″

Length: 4.96″

Width: 0.96″

Action Type: Single action

Operation: Simple blowback

P-3AT Pistol .380 ACP

Manufacturer: Kel-Tec CNC Inc., Cocoa Florida, USA

Weight Loaded/Empty 10.6 oz/8.5 oz

Material: Polymer frame (Dupont ST-8018), aluminum frame insert (7075-T6), steel barrel & slide (4140 Alloy)

Magazine Capacity: 6 shots

Safety: Passive hammer block safety

Height: 3.60″

Length: 5.16″

Width: .74″

Action Type: Modified double action

Operation: Locked breech

Get More Carry Options content!

Sign up for the newsletter here: