Cimarron Cartridge Conversions

Replicas Of Our First Cartridge Guns

Are Better Than The Originals.

One of the great passions of my life, handguns, go back more than 500 years. Even though the idea of the cartridge is nearly 200-years old, powder, ball and cap were state-of-the-art for most of the 19th century. A Frenchman patented the idea in 1812. Another Frenchman came up with the pinfire cartridge in 1846 and Flobert exhibited a rimfire cartridge at the London Exhibition in 1851. Meanwhile, on this side of the Atlantic, Smith & Wesson received a patent for a centerfire metallic cartridge in 1854 and then around 1856 developed the first true rimfire cartridge as it is known today.

Sam Colt held the patent for revolving cylinders, one that would run out in 1856. A Colt employee by the name of Rollin White held the patent for bored through cylinders to accept metallic cartridges. Sam Colt wasn’t interested, however Smith & Wesson was and in late 1856 Rollin White, Harold Smith, and Daniel Wesson met with the result being Smith & Wesson granted exclusive rights to the White patent. One year later, S&W introduced the first successful cartridge-firing revolver, a seven-shot, tip-up, chambered in .22 Short. Sam Colt still ignored the concept. He died in 1862 while Colt was fulfilling a very lucrative contract supplying 1860 Army .44 cap-and-ball revolvers to the Union Army, however many of Union officers carried a S&W No. 1 .22 or No. 2 .32 Rimfire as a hideout gun.

The First Big Bores

In 1864 a New York firm tried to con-tract 3,000 large-frame .44 revolvers from Smith & Wesson. Two things pre-vented this from happening, S&W production was totally allotted to their little pocket guns and Rollin White would not agree. The history of the sixgun could have been changed dramatically if this contract had been fulfilled. White’s patent was due to run out in early 1869 and his appeal for an extension was denied leaving the door open for any company to produce big-bore cartridge revolvers. However, it was neither Smith & Wesson nor Colt who would be first. In 1868 Remington and Smith & Wesson came to an agreement with Remington converting their New Model .44 percussion revolvers to .46 Rimfire.

After the Civil War, Colt decided the future really was in metallic cartridges. In late 1868 Colt 1860 Army percussion revolvers used the Thuer Conversion to circumvent the White patent. Instead of a bored-through cylinder, this conversion used a tapered cartridge which entered from the front of the cylinder. It was not very successful.

Meanwhile in late 1869/early 1870 Smith & Wesson introduced the Model No. 3 American, six-shot, top-break revolver chambered in a new centerfire cartridge — the .44 American. The United States Army ordered 1,000 of the new Smith & Wessons. That really got Colt’s attention! With this beginning switch to cartridge-firing sixguns what was the Army to do with all the 1860 Army revolvers on hand and what was Colt to do with all the factory parts they had for assembling more 1860 Models?The answer came from C.B. Richards, a Colt employee.

Richards Rescue

Using Richards’ patent, Colt began converting 1860 percussion revolvers to the Richards Conversion firing the .44 Colt. Basically the back of the 1860’s cylinder was cut off, the frame was fitted with a breechplate and loading gate, the ball seater removed and an ejector rod assembly attached to the right side of the frame. Some of these .44 Colts were used by the Army well into the 1880s even though the Colt Single Action Army was officially adopted in 1873.

Cartridge Conversions

The Richards Conversion, the improved Richard-Mason Conversion, and the 1871-72 Open Top all served as transition revolvers from the 1860 Army to the Colt Single Action Army. They are a very important part of sixgun history and original examples are quite valuable. Fortunately for those who wish to shoot such revolvers, all three have been available for quite some time with most of them being chambered in .44 Colt.

This cartridge, in both its original and modern version, has a smaller rim than the .44 Russian as the cylinder of the converted 1860 Army is not large enough to accept the larger rims on the Russian without them overlapping. Now thanks to Cimarron Firearms we have the newest version of the Richard Conversion, the Richards II, which not only has room for the larger diameter rims, the frame and cylinder have been made larger to accept the .45 Colt. It is also available in .44 Colt, .44 Special, and .38 Special.

In comparing the Cimarron Richards II to Diamond Dot’s original Richards Conversion (see June 2006 GUNS), I find the latter has a cylinder diameter of 1.621″ while the newer version measures 1.677″ to handle the larger .45 Colt as well as the rims of the .44 Special. The original Richards Conversion used a heeled bullet of the same diameter as the outside of the brass cartridge case. To be able to fire the original, (we do shoot it with black powder only) I load a hollowbase pure lead bullet into modern .44 Colt brass. Upon firing, the base of the bullet expands to contact the rifling. The Cimarron replica makes things much simpler. Whether using .44 Colt, .44 Special, or .45 Colt versions, they are built to handle standard smoke- less powder loads and the barrels are dimensioned as any current .44 Special or .45 Colt so it is not necessary to use expanding bullets.

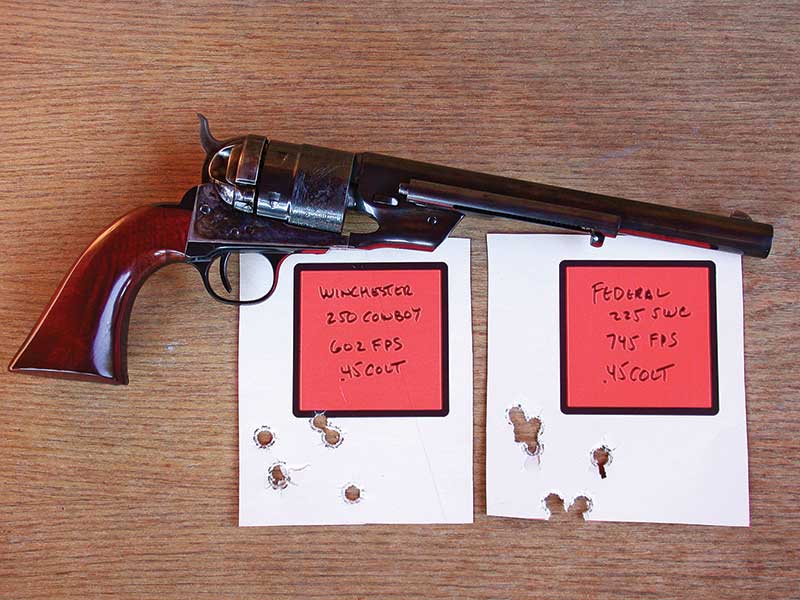

.45 Richards Cartridge Conversion

The .45 Colt Cimarron Richards II is an all steel revolver instead of having the brass triggerguard of the original. Mainframe, hammer, breech plate, and loading gate are all case colored with the balance of the revolver being finished in a nicely polished deep blue black. The grip frame is the comfortable 1860 Army very well fitted with one-piece walnut stocks with good grain. For my eyes and hold, it shoots about 6″ high with most loads. This can be corrected by the installation of a higher front sight, or probably an easier solution would be to deepen the rear sight notch on the hammer and take a little off the top on the hammer to effectively lower the rear sight. The Richards II loads the same as any traditional single action, that is, the hammer is placed on half cock to allow the cylinder to rotate and opening the loading gate accesses the cylinder for loading or unloading. The ejector rod has a large semi-bull’s-eye head making it very easy to operate. Seven different standard .45 Loads were used for test firing the Cimarron Richards II. Five-shot groups at 20 yards averaged well under 2″ with the best load being Winchester’s 250-grain Cowboy load at 11⁄4″ for five shots. Although far from being authentic, and perhaps even bordering on blasphemy, I tried the thoroughly modern CCI Blazer 200-grain jacketed hollowpoints in this re-creation of a nearly 150-year-old revolver. The results were exceptionally gratifying with five shots going into 13⁄8″. I’m certainly not going to recommend the 1860 Richards II as a self-defense revolver, but if it is all one has, it would certainly work.

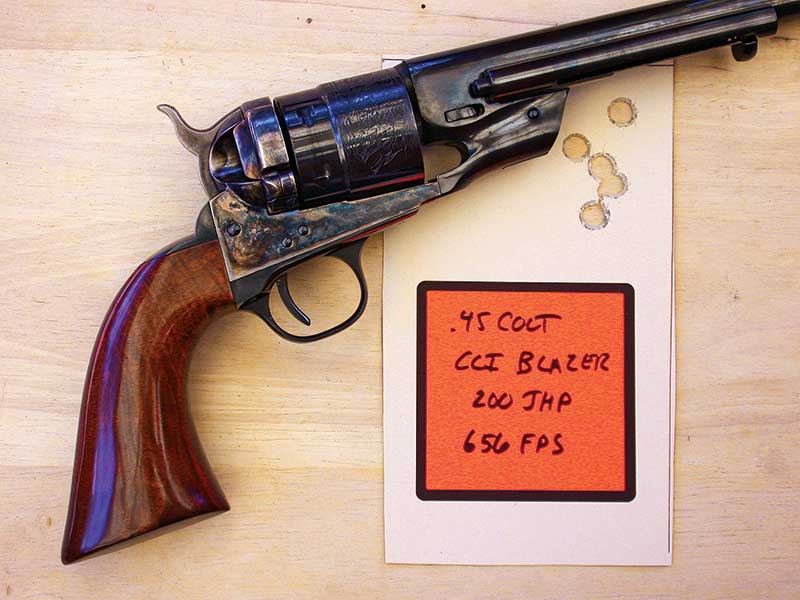

Remington .45 Colt Conversion

Earlier, I mentioned the Remington .44 New Army percussion revolver being the first sixgun actually converted to cartridge firing. Cimarron has not for-gotten the Remington and also offers an 1858 conversion in .45 Colt. Once again it was necessary to increase the size of the cylinder to be able to place six .45 Colt rounds in the cylinder. In measuring a replica .44 Model 1858 I find a cylinder diameter of 1.604″ while the Cimarron Conversion measures 1.651″; even though the cylinder has been made larger, this sixgun is still for standard .45 Colt loads only whether using smokeless or black powder.

The Remington conversion is quite different than the Richards II. The breech plate/loading gate is somewhat of a double saddle construction. That is, it slides into place and clips over both sides of the topstrap and both sides of the mainframe.

When the cylinder is removed, the breech plate can also be removed without tools and the percussion cylinder, which is supplied with this Cimarron Cartridge Conversion, placed in the frame. This conversion also follows the original in that the bullet seater is maintained and the top of the forepart is notched to hold the ejector rod in place. For loading or unloading, the bullet seater is unlatched, the ejector rod rotated 180 degrees and is then ready for punching out empty cartridges. There is no ejector rod spring, however it is quite easy to use the rod by pushing and pulling when grasped with thumb and forefinger.

The breech plate/loading gate and .45 Colt cylinder of Cimarron’s 1858 Remington cartridge Conversion (above)

are easily removed and replaced with the percussion cylinder. The ejector rod on the Cimarron Remington .45 Colt

is held in place by the bullet seater. The Remington .45 Colt from Cimarron (below) loads in the traditional manner.

Superior Design?

Finish of the Cimarron Remington is very well carried out with a nicely polished deep blue-black finish on the entire sixgun except for the highly polished brass triggerguard and the purplish color on the breechplate. Unlike the Colt, the mainframe and grip frame are all one solid piece instead of three pieces. The triggerguard is not part of the grip frame and is an easily removed affair by the loosening of one screw.

The grip frame on the Remington never loosens as it does it on all other traditionally-designed single-action sixguns. The original Remington was the stronger of the two revolvers, however the original Colt had a more comfort-able grip frame and also pointed much easier, at least for me. The grips are well-fitted walnut, though a little wide at the bottom for my comfort, a situation easily fixed.

There is no doubt the Remington with its solid frame was superior to the Colt. At least the Army thought so and required a solid-top frame on the Colt Single Action Army. The sighting set up on the Remington is also superior to the Colt Percussion revolvers with the rear sight cut into the top of the frame and, in the case of this conversion, the front sight is on a dovetail for easy replacement should a taller or shorter height be required. In my case, this .45 Colt Remington Conversion shot right to point of aim. Six standard .45 Colt loads were used in test firing the Cimarron Remington with once again groups averaging well under 2″ for five shots at 20 yards, and also once again the most accurate load was Winchester’s 250-grain Cowboy RNFP (roundnose flat-point) load.

Spaghetti Sixgun

The third revolver in this trio of Cimarron Cartridge Conversions is the “Man With No Name” sixgun. Not only have the Italians provided us with replica revolvers for more than 40 years, they have also given us a long list of Spaghetti Westerns. Fortunately, both movies and firearms have improved significantly during this period of time. This final new offering is patterned after a sixgun carried by Clint Eastwood in The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. In the movie, the guns were designed to give the cap-and-ball flavor of the Civil War era and provide the propmaster with the ease of maintenance the cartridge revolver provides.

Based on the 1851 Colt Navy, this conversion is different than the other two as the breechplate is an integral machined part of the frame and not a separate piece. The barrel and bullet seater assembly are traditional 1851 Navy and the cylinder is accessed by a loading gate, however there is no ejector rod for removing cartridges. I did not find this a problem as it is chambered in .38 Long Colt/.38 Special. Since it is the designed once again for standard-pressure cartridges only, fired cartridges are easily removed and will often fall out of their own accord when the barrel is pointed skywards. If not, they are easily removed with a thumbnail or punched out from the front with a small dowel.

The cylinder and barrel are nicely polished deep blue black, the main-frame, hammer and bullet seater are case colored, while the grip frame —both backstrap and triggerguard — are brass. One-piece walnut stocks, which in this case have exceptional grain, are available in plain, smooth wood, or as on our test sixgun with the silver rattlesnake on the right grip.

This beautifully balanced and easy shooting cartridge conversion is a prototype and the first one out of the factory. Before I received it, it had been around to a few other places for photo-graphs only. As a prototype, it had a few bugs, but I shot it anyway with good results. I didn’t add it to the accuracy test chart because I would prefer to wring out a production version. Nevertheless, it is unique enough to be included here.

Cimarron Firearms has come along way since Mike Harvey first purchased a little import company known as Allen Firearms. I was the first to write up Cimarron too many years ago and I have been well pleased to see the continued upgrading of Italian replicas due in no small part to Mike’s efforts. Not only has the quality improved significantly it has gone hand in hand with a higher level of authenticity. These three revolvers are all manufactured by Uberti, however the Cimarron catalog contains 82 firearms, many in several calibers, with both revolvers and long guns not only by Uberti, but Pedersoli and ArmiSport as well. Replicas of nearly every Colt and Remington single action, Winchester levergun, Sharps, Springfield, and Winchester single-shots from Cimarron make it very easy to connect with our frontier past.

Get More Revolver Content Every Week!

Sign up for the Wheelgun Wednesday newsletter here: