.38 Long Colt

Bad Press Aside, This Is One Sweet-Shooting Load

Without a doubt the most denigrated American military handgun cartridge ever is the .38 Colt (aka .38 Long Colt). It is said to have been the cause of death for many an American soldier during the Philippine Insurrection (1899-1902).

Which was why the U.S. Army returned to .45 caliber with the Model 1909 revolver (Colt New Service) and then — two years later — to the Model 1911 .45 Auto. The Philippine stories were probably true, although stopping drugged, fanatical Moros with any handgun would likely have been difficult.

For most of my life — like everyone else — I turned my nose up at it and still wouldn’t bet my life on a handgun so chambered. However, if you want a recreational round with an undeniable historical aura, it fits the bill perfectly.

Revolver Options

I’ve owned several .38 Colt handguns (to the best of my memory, none were stamped “.38 Long Colt”). They’ve ranged from a couple of little Colt Model 1877 DAs to one U.S. Model 1903 and a modern conversion done on one of the fine 2nd Generation Colt 1861 cap-and-ball revolvers (I understand the gunsmith no longer does them, so I won’t mention names). And of course any .38 Special or .357 Magnum revolver can safely fire .38 Long Colt.

Here’s a brief synopsis of the .38 Colt/Long Colt story: It was introduced in the early to mid-1870s for several types of Colt revolvers. Some were cap-and-ball conversions, others small pocket pistols.

In 1877 it was one of the introductory calibers of Colt’s double action, soon nicknamed the “Lightning.” Case length was 0.88″ and heel-type bullet weights were 130–150 grains over about 18 grains of black powder. Now get this: Bullet diameter was actually about .375 to .378″ — not .357″ — as was the later .38 Special.

Bullets, Handloading Tips

In the 1890s .38 Colt cases were lengthened to 1.03″ and the 150-gr. bullet diameter reduced to .357″ over 19 grains of black powder. The barrels were still being made with nominal .375″ rifling groove diameter. Colt didn’t stop the practice with the SAA/Peacemaker until 1914 and by then its other .38 Colt revolvers were no longer produced.

So how can a .357″ bullet leave a .375″ barrel with any sort of accuracy? The trick was to make them very soft and give them a deep hollow base. This system worked well and still does.

This brings us to handloading. The No. 1 Rule is this: if the revolver you are shooting is a .38 Special/.357 Magnum, just use .357/.358 solid-base, lead alloy bullets weighing 145 to 155 grains loaded normally. A charge of 2.7 to 3.0 grains of Bullseye will duplicate original factory ballistics (about 760–770 fps).

If the .38 Long Colt revolver you wish to shoot is an original or a facsimile such as my “modern” conversion, then the best choice is a 145–155-grain soft lead, hollow-base bullet. In past years hollow-base bullet molds were not hard to find. Today they are. Commercially made bullets cast of a soft alloy are available from Buffalo Arms of Sandpoint, Idaho.

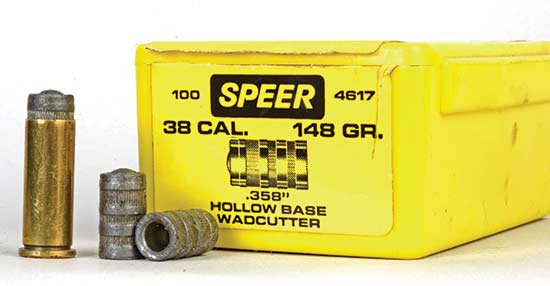

I do have a hollow-base bullet mold for a 150-gr. RN from a now out-of-business manufacturer. When shooting black powder these are lubed with black powder-friendly SPG. That said I have over 500 rounds of good .38 Long Colt ammo loaded with smokeless powder and hollow-base bullets (Speer 148-gr. WCs meant for .38 Special target shooting). I load them over 3.0 grains of Bullseye or Titegroup and they shoot beautifully from my conversion.

Final Note

Two words of warning: (1) If shooting a black-powder era .38 Colt made prior to 1900, I would only use black powder. (2) If handloading with smokeless powder and 148-gr. hollow-base wadcutters, seat the bullets out 1/4″ or so from the case mouth instead of flush with it (as with .38 Specials). Otherwise the powder chamber of the shorter .38 Colt might be “crowded” a bit.

The bottom line? A Western-style .38 Long Colt sixgun may not be much of a manstopper, but it makes a fine plinker.

Buffalo Arms

Ph: (208) 263-6953

www.buffaloarms.com

SPG Sales

Ph: (660) 988-4099

https://shopspg.net