WWI Classic Returns

Smith & Wesson Model 1917 .45 ACP

As a general rule double action revolvers don’t have the historical aura around them, as do ones like the S&W Model No. 3 “Schofield” single action or the Colt Model 1911 autoloader. One exception to the rule is the Smith & Wesson Model 1917.

It was developed during a time of national emergency and made its mark with the US military in two World Wars. Furthermore, it started the trend of chambering revolvers for the .45 ACP (Automatic Colt Pistol) still popular today.

Ninety years ago when the United States entered World War I, the American military found itself unprepared in regards to nearly all military equipment from handguns to aeroplanes.

The US Army’s official handgun was the Model 1911 autoloader made by Colt. Not nearly enough of them were in service to provide for the rapidly expanding military. At the time, both Colt and Smith & Wesson were manufacturing large bore, double-action revolvers.

Some far-thinking engineer at the latter company had already conceived of a manner in which these revolvers could be adapted to fi ring the rimless .45 ACP by snapping the .45 ACP rounds into stamped spring- steel clips, which would then serve as the cartridges’ rims and give the revolver extractors something to push against. Because these little clips held three cartridges in a semi-circular pattern they came to be called “half-moon” clips.

The US Government gave contracts to both Colt and Smith & Wesson for revolvers collectively named “US Model 1917.” These handguns were simply Colt’s standard New Service and Smith & Wesson’s N-frame sixguns. Interestingly Smith & Wesson gave their Model 1917s the same level of polish and blue as their commercial handguns, but Colt put a dull polish on theirs. Grips for both were simple two-piece smooth walnut.

According to US Infantry Weapons Of World War II by Bruce Canfield, Colt sold about 150,000 Model 1917s to the government and Smith & Wesson’s total was slightly greater at about 153,000. These .45 caliber revolvers saw considerable use on the battlefields of World War I. They must have suffered considerable losses because (also according to Canfield’s book) when they were put into storage after the conflict only 96,530 of the Colts and 91,500 of the Smith & Wessons were in government hands.

Into The Breech Again

Now fast forward to 1941 when it was obvious the United States would become involved in World War II. Again there was a shortage of Model 1911 autos, so the trusty Model 1917s were pulled out of storage and issued. According to Canfield, most of these revolvers were retained for use in the continental United States with military police units, prisoner of war camp guards and the like. That said, Canfield also relates just under 21,000 were actually sent overseas for combat duty and existing photographs document their use by combat troop such as US Army soldiers in Europe and Marines on Pacific islands.

On a personal note, my own uncle, the late James Virse of Belfry Kentucky, was an infantryman with the 3rd Marines during the 1944 invasion of Guam. He told me after the island was declared secured there were still numerous Japanese stragglers wandering around. Therefore all Marines were ordered to go armed at all times. He said he scrounged up a Model 1917 .45 (but couldn’t remember if it was a Colt or S&W) and carried it with him in place of his much heavier M1 Garand.

The concept of a revolver firing the big .45 autoloader cartridge caught on with the gun buying public after World War I, so both Colt and Smith & Wesson kept Model 1917 revolvers in their catalogs. Colt only added the cartridge as a chambering in their New Service model but Smith & Wesson actually retained the Model 1917 moniker.

Colt stopped all production of their New Service revolvers about 1944, but Smith & Wesson kept their Model 1917 cataloged until 1949. Then, they introduced a new version called the Model 1950 Military, which turned out to be nothing more than the old Model 1917 with redesigned internals, checkered Magna-style grips, and missing the lanyard ring. In 1957 when they introduced model numbers instead of names, the Model 1950 Military became the Model 22.

When Smith & Wesson discontinued production of many of its large frame double action revolvers in 1966, the Model 1950 Military/Model 22 became one of its least produced standard model revolvers with only 3,976 made. But don’t forget this — in 2005 Smith & Wesson resurrected the Model 22 in a slightly altered form as its second version of a Thunder Ranch Revolver. (Between the US Military, the Brazilian Government and commercial sales, well over 200,000 Model 1917s had been made.)

Interest Renewed

That’s the story of the Model 1917 revolvers in a nutshell, and such would be merely a historical footnote except for today’s management at Smith & Wesson. Not only have they developed such startling new things as super lightweight “Scandium” revolvers, but they are able to look backwards, too. That’s what I learned at SHOT Show 2007 when I dropped into their booth. There in a display case were three versions of a new Model 1917 — full blued, full nickel-plated, and a rather odd duck, a Model 1917 with color case hardened frame. I immediately informed our esteemed editor at the time, “Hey, I get to do the new S&W 1917s!”

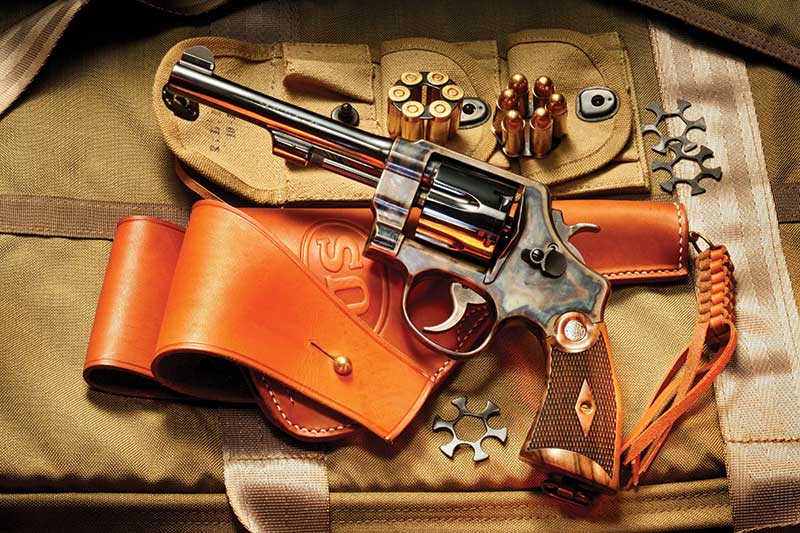

And they were delivered into my awaiting mitts. The original Smith & Wesson military Model 1917s were all of a type. They were blued with 5-1/2″ barrels, smooth walnut stocks, color case-hardened trigger and hammer and a lanyard ring in the butt.

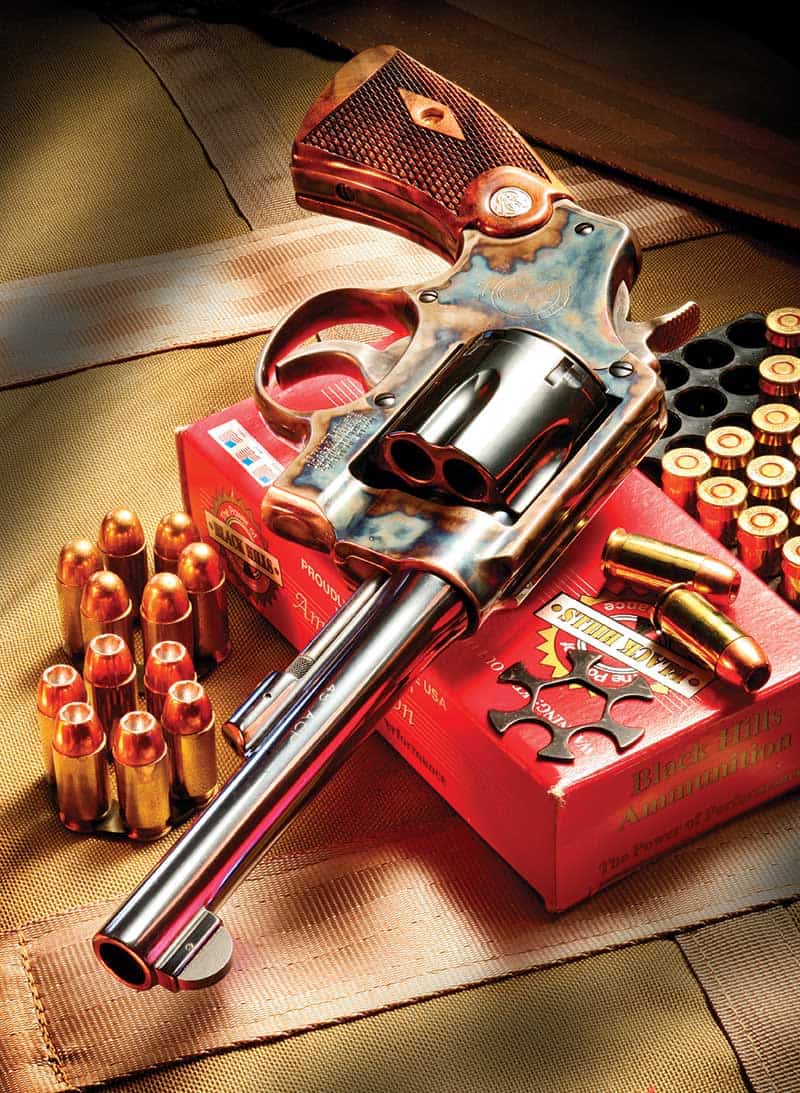

Sights consisted of Smith & Wesson’s distinctive “half-moon” front with a groove down the revolver’s topstrap for a rear one. After the Model 1917 turned commercial, about the only thing changed was the stocks were checkered and they later evolved into the more hand-filling Magna-style walnut type. In Roy Jinks’ book History Of Smith & Wesson, there is no mention made of commercially sold Model 1917s being nickel-plated, but it is certain the later Model 1950 Military was offered so finished.

The Same, But Different

Externally, the new Smith & Wesson Model 1917s are similar, but not dead-ringers for vintage ones. I have a World War I vintage Model 1917 in my collection, so I was able to compare them. The hammer spur on the new 1917s are .400″ wide, while the originals were a narrow .26″. Both types were checkered though. The front sight on the vintage 1917 was forged integral with the barrel. With the new revolver, the sight base is integral with the barrel, but the sight blade itself is pinned in. Both types have the old half-moon shaped front sight with the original being .073″ wide and the new one .125″.

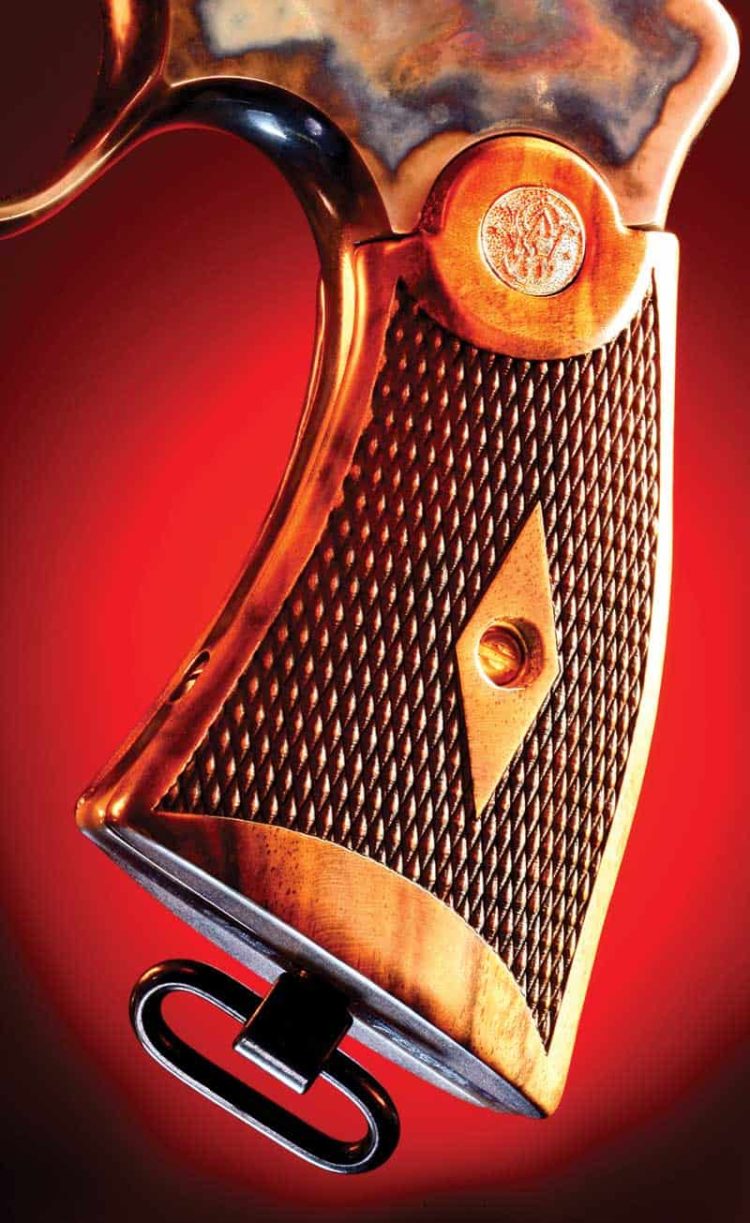

Even the grips on the new gun duplicate those slender checkered-style types found on early commercially sold Model 1917s. And both models have the un-shrouded ejector rod incorporated in N-frame Smith & Wesson revolvers circa 1916. One really surprising item was the fact the new Model 1917s have the fourth screw on the revolver’s sideplate, the one high up, discontinued on N-frames way back in the 1950s.

The biggest difference on the new 1917s a discerning buyer will notice is the new key-lock slot on the left side of the frame just above the cylinder release button. Like just about everyone else on the planet, I don’t like it, but it’s a lawyer-mandated thing and we’re just going to have to live with it. Also, the new Model 1917s don’t have the firing pin mounted on the hammer. Instead, it is frame mounted, but since such a thing isn’t visible when the revolver is being fired, it doesn’t bother me as much.

Tight Fit

The barrel cylinder gap on the new blued Model 1917 is very tight. It will accept a .003″ feeler gauge but not a .004″ one. By comparison, my 90-year-old original will accept a .011″ gauge, but not a .012″ one. Trigger pull on the new blued Model 1917 is 5-1/2 pounds but crisp. Trigger pull on the new nickeled 1917 is 5-1/4 pounds and I didn’t measure the pull on the color case hardened one for a reason to be pointed out shortly. I can’t measure a trigger pull as heavy as double action ones always are, but these new ones are smooth and not overly heavy. Fit and finish of all three of these new Model 1917s are nice. The edges have not been overly buffed in the polishing process, and the checkered grips fit the grip frames nicely.

I like the blued version much. I like the nickel-plated one almost as much. Being a traditionalist, I don’t personally like the case hardened one, but it’s done well and may appeal to you. Historically, Smith & Wesson never color case-hardened the frames of their revolvers. They were either blued or nickel plated with color case-hardened triggers and hammers. Colt was the manufacturer set on color case hardening revolver frames, but even then mostly just their single actions.

All the firing was done with the blue and nickel-plated versions. In the beginning my intention was to only use 230-grain FMJ factory loads in these guns, as that is the type of ammunition they were designed around back in 1917. But when I looked at my ammo shed, the only load on hand was by Black Hills Ammunition. Therefore I expanded things a bit and included 230-grain JHPs by both Black Hills and Winchester.

First shooting was done with the revolver mounted in a Ransom Pistol Machine Rest to see the basic level of mechanical accuracy of which it was capable. I wish I could report these new Model 1917s were tackdrivers, but alas, they weren’t particularly accurate revolvers. Neither have been the other two or three Smith & Wesson Model 1917s I’ve owned over the last 40 years and my Model 1950 Military/Model 22. Twelve-shot groups at 25 yards were running in the 3″ range with one or two going under that and another one or two going over. Three-inch groups are not horrible, but not spectacularly precise either.

Next, shooting was done at paper targets, steel dueling trees and ordinary chunks of firewood with the new Model 1917 held in my own two mitts. Neither 1917 hit point of aim, but the blued one was closest. Fired from 50′ it was on for elevation but approximately 2″ right for windage. The nickeled one’s point of impact was 3-1/2″ high and a full 4″ right of center. This shooting was with 230-grain FMJ “ball” from Black Hills Ammunition. Fixed sight revolvers can be sighted in; I’ve done many, but it is always nice if they are pretty close right out of the box.

My first S&W 1917 came to me in a gun trade in 1968 and in the nearly 40 years since I’ve owned a few others. They’re not the most practical handgun for most shooting purposes but neither are Colt SAAs, M1 Garands, or just about any other firearm once a military weapon. But, they are historical and always interest a good segment of the shooting community as I’m sure these Smith & Wesson Model 1917s have.

Get More Revolver Content Every Week!

Sign up for the Wheelgun Wednesday newsletter here: