Hunting With Gibbs

Making Magnums From the Ordinary

The Springfield had been restocked in plain walnut, carefully inletted. Its shape and age-hardened Pachmayr pad, I figured, dated it to the ’60s. The safety and bolt handle swept low, dodging Buehler rings gripping a J.C. Higgins 4X. The rest of the metal was pretty much as issued, save where the sights had been. What sold me was the barrel stamp: .30 Gibbs.

The proprietor winced at my offer, scratched his chin. “OK.” I dug out a wad of 20s before he could change his mind.

“Next year, Spud, you’ll see me out on Bone Mountain with one of them Gibbs .30 Magnums.” So wrote Francis Sell in his fine book on deer hunting, which I read soon after its 1964 publication. I’d yet to kill a deer, but I wondered, “Who was Gibbs anyway?”

Born November 12, 1915, Manolis Aamoen Gibbs lost the sight in his right eye early to typhoid. He learned to shoot from the left shoulder. Soon after graduating high school in Gainesville, Texas, he traveled to California, land of promise for Dust Bowl refugees. On the train carrying him to Richmond, he marveled at the Rocky Mountains. The name had a big, rough-edged ring. He would adopt it.

New Name, New Game

The newly minted “Rocky Edward Gibbs” learned the gunsmith trade, then entered his rifles in competition and refined his marksmanship. Contest scores combined group sizes at 100, 200, 300 and 400 yards with bullet drop at 400 so both accuracy and flat arcs mattered. Denied victory with the .270 Winchester and .270 Ackley, Rocky set a match record in 1953 with his own .270 wildcat. The chamber, in a Remington Model 721, was cut with a Keith Francis reamer leaving a 35-degree shoulder and a short .250 neck. He would use this formula to hotrod the .30-06 case with bullets of other diameters, six of them within a year or so.

In 1955 Rocky left California for a 35-acre tract near Viola, Idaho, arriving in a March blizzard. There he set up a 500-yard rifle range and converted a metalworking shop into one equipped for rifle building and handloading.

No stranger to hyperbole, Rocky claimed his .270 Gibbs was “the best all-around cartridge for a handloader.” Even Jack O’Connor acknowledged its merits: “As far as I can tell,” he wrote in Outdoor Life, “Brother Gibbs doesn’t do it with mirrors.” Claims of 63 grains of IMR 4350 in his .270 sent 130-gr. bullets at 3,430 fps surely fueled many campfire debates. How could an ’06-based wildcat match the .270 Weatherby? However, Rocky held firm. He insisted 139-gr. missiles from his 7mm galloped out the muzzle at 3,300 fps. This wildcat got a lukewarm reception, in part methinks because Warren Page, shooting editor of Field & Stream at the time, was giving his 7mm Mashburn steady ink. When the belted 7mm Remington Magnum arrived with the Model 700 in 1962, there was no need for either.

Yet Rocky was colorful and his cartridges put lightning-bolt speeds in reach of anyone willing to re-barrel or re-chamber a .30-06. In his era, guns such as the surplus Springfield 03A3 which caught my eye sold for $29.95.

Double-Shouldered Data

To make a Gibbs case, you must first relocate the “datum line” which arrests forward movement of the cartridge to establish proper headspace. To make .30 Gibbs cases from .30-06 brass, you expand necks in a .338-06 or a .35 Whelen sizing die, then run them through a .30 Gibbs sizing die. The cases now have two shoulders. Firing modest loads in a .30 Gibbs rifle, you erase the lower, original shoulder. Shooters in Rocky’s day could streamline the process with a Gibbs Wildcat Case Forming Tool.

These days, commercial .35 Whelen brass eliminates the need to neck up before necking down to deliver a .30 Gibbs hull — though .338-diameter shoulders are adequate to establish headspace, and you’ll lose fewer cases by working the brass less. Incidentally, I avoid nickel-plated brass for wildcatting, as the nickel can flake off, forming grit when hulls are given new or sharper shoulders.

I’m sweet on the .30 Gibbs because it’s more efficient and more versatile than the smaller bores such as the .240 Gibbs. It has nothing ballistically on the 8mm Gibbs, which Rocky fashioned to salvage 8×57 Mausers pulled from the wreckage of World War II. However, then — as now — options in .323 bullets barely outstripped choices in Size 16 shoes. In addition, few stateside shooters were rushing to adopt the favored bore of the Third Reich. The .33 Gibbs might have fared better had not Winchester’s .338 Magnum appeared about the same time.

With 180-gr. bullets in a tight footrace with factory loads from the .300 Holland & Holland, the .30 Gibbs was rightly considered a “poor man’s magnum.” It seemed to me an ideal elk cartridge.

Building A Wildcat

After several passes with Hoppe’s on brush and patches, the bore of my Springfield gleamed. No indication it had been damaged by corrosive priming. Replicating the way hunters in the 1960s made .30 Gibbs cases, I necked one batch of .30-06 hulls to .358, another to .338. The bump to .338 was noticeably easier. A pass through Redding’s .30 Gibbs sizing die then formed a second shoulder and new datum line.

A critical caveat: Unlike the .30-06 Ackley Improved, the .30 Gibbs cannot safely be fire-formed from unaltered .30-06 brass. You must form the new shoulder first! Igniting .30-06 cartridges in a .30 Gibbs chamber causes a condition of excess headspace, with the risk of case separation. Escaping gas can damage your rifle and test your health insurance!

New shoulder in place, I loaded mild 50-gr. charges of IMR 4350 behind 165-gr. bullets to erase the old. Cases emerged perfectly sculpted. Inspired, I increased charges to bring velocities 100 fps higher than those of commercial .30-06 ammunition did. No problem! Accuracy with these fire-forming loads averaged just over 2 MOA.

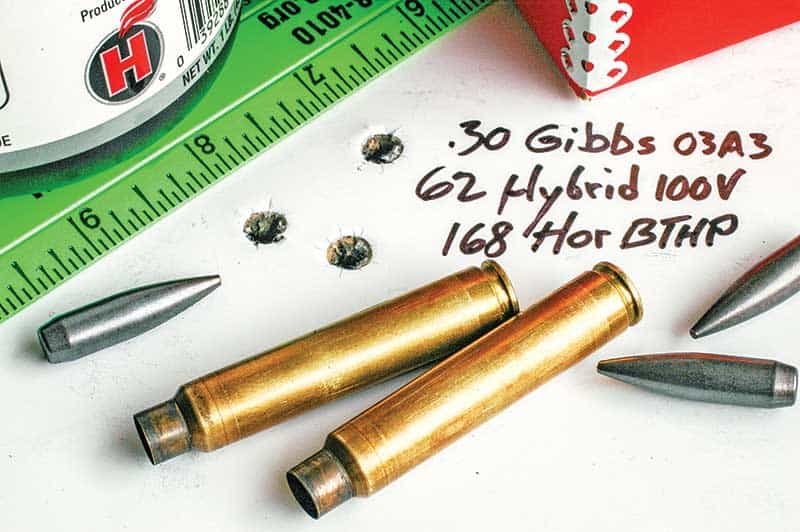

Accuracy improved with the fully formed cases — and after I replaced the ancient scope with a 3-9x Leupold Vari-X II. With 150- and 165-gr. bullets, I came to favor Hodgdon Hybrid 100V powder. The 180s performed best with IMR 4451 and RL-19, though H414 also delivered good results. No tackdriver, the 03A3 drilled 1¼-MOA groups with my favored loads — certainly adequate for hunting. In a nod to my first elk load, 180-gr. Speers in a .300 H&H, I decided to hunt with these bullets over a charge of 4451.

Into Rough Country

The Gibbs merited a hunt in storied elk country, so I booked a pack trip with Bill Perry’s Hidden Creek Outfitters into Wyoming’s Thorofare drainage. The prospect of hunting the Thorofare was heady indeed. Then, short weeks before pack-in, I broke my ankle. Graciously, Bill agreed to re-schedule, as reports came of giant bulls flocking off the peaks ahead of early snows. Mules plodded the 26 miles to trailhead under tons of meat. Massive antlers arced over packsaddles to hook brush on both sides, beam tips brushing fetlocks.

I healed, readied the Gibbs and a year later swung into the saddle, jacket off under Indian-summer skies. Bulls wouldn’t migrate early this September. Drainages thick with grizzly tracks led us to wall tents under vaulting crags. For three days, I poked through thickets just under the rims, glassing scattered herds. A raghorn 5-point looked me over. I left him alone to grow up. On a hunch, I climbed the same ridge next morning.

Dawn was a titanium tinge when a bull brayed far above me. On steep trails I scrambled toward him. Then a twig snapped. Antlers flickered. My crosswire found a slot, high on rib. Hit but not dead! My follow-up left as scree underfoot gave way, the muzzle raking sky as I windmilled to stay upright. Again the bolt flicked home. Bang! A perfect call. Two Speers were suddenly too much. The 6-point collapsed.

My Springfield had proved good company on the elk trails. More than a tool, it’s a link to another era, to people, events and places erased by time but tangible still in the heft of my 03A3. Thumbing a .30 Gibbs into the well, I’m no better able to kill an elk than if it were another of the 38 cartridges I’ve used hunting these great animals. Yet the Gibbs has a richer past than most. It makes a hunt memorable, whether a shot comes or not.

Postscript

In 1973, leukemia would claim Manolis Aamoen “Rocky Edward” Gibbs at the age of 58. Gibbs had a flair for the dramatic and apparently guarded his own raw range data. Rumor had it he instructed his wife, upon his death, to burn his notes. His cartridges, with those of Donaldson and Ackley, Mashburn, Weatherby and others, mark the golden days of wildcatting. Long before the advent of chassis-stocked bolt actions, Gibbs helped shooters send bullets faster and hit targets farther off — all from $30 infantry rifles and pails of fired ’06 hulls.