Rolling-Block Thunder

A single-shot .50-caliber powerhouse pistol!

While the American Civil War was raging, the U.S. Navy was already casting about for a metallic cartridge replacement for their cap-and-ball revolvers. When they functioned, they functioned well, but cap-and-ball handguns, exposed to a humid saltwater environment, had their drawbacks. Charges got damp and wouldn’t fire. Reloading was slow. Percussion caps were hard to handle and susceptible to corrosion and the nipple channels themselves could corrode and become clogged if not kept scrupulously clean.

The Navy had purchased approximately 6,000 revolvers from Remington during the war and, in 1864, the Bureau of Ordnance inquired if Remington had “… taken steps to prepare a model single-barreled pistol suggested during a personal interview at the Bureau some time back. Such a weapon is very much needed for naval purposes.”

Remington was indeed in the process of refining what would possibly be their most successful design, the rolling-block, breech-loading action, patented by Lenard Geiger in 1863 and refined by a fellow mechanic at Remington, Joseph Rider.

The rolling-block action was elegant in its utter simplicity, consisting primarily of two parts — a rotating breechblock and a hammer locking the breechblock in place at the moment of firing. It was fast to operate (it was said a competent rifleman could get off 17 aimed shots a minute). It was strong and readily made the transition from black powder to modern smokeless cartridges. And it was safe — as long as the block was open, the trigger was blocked and could not be pulled.

Remarkably, as a single-shot pistol model, it was in production at Remington from 1865 until 1909, and as a military rifle as late as WWI when it was supplied to the French in 8mm Lebel. Licensed to countries around the world, military rolling-block rifles were produced in the millions.

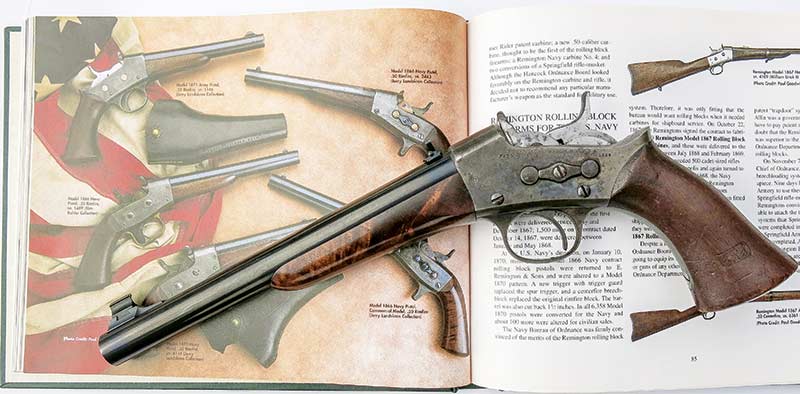

The Old Army/Navy Game

Did the Navy get their pistols? Yes, beginning in 1866 with the 1865 Model Navy. It was chambered for a .50-caliber rimfire cartridge carrying a 300-gr. bullet powered by 30 grains of black powder. It featured an 8.5″ browned barrel, sheathed spur trigger and walnut grips while the receiver, breechblock, hammer, trigger and sheath were color case hardened. Total production is estimated at 6,500. In 1870, most of these early production models were converted by Remington to .50 centerfire and refitted with traditional trigger guards while the barrel was shortened to 7″. In collecting circles they’re known as the Model 1867 Navy. Confusing, isn’t it?

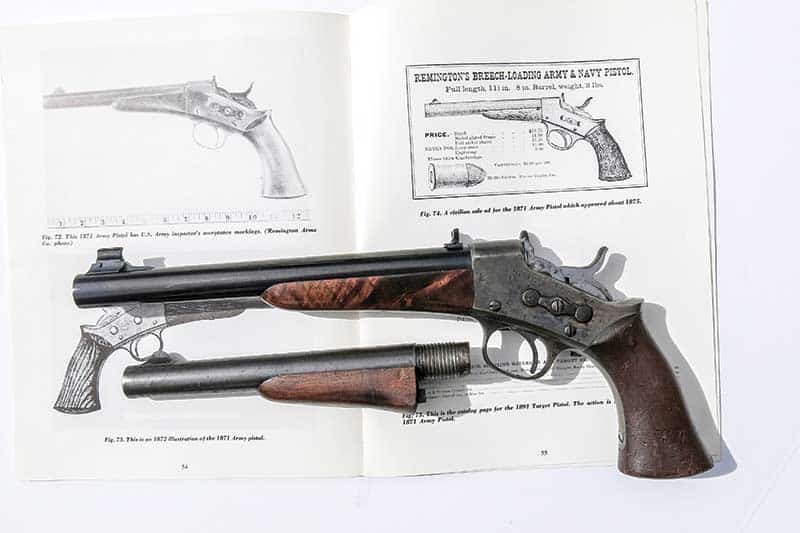

Which brings us to the Model 1871 Army pictured here. This model is the last of the Remington military single-shot pistols. Based on the recommendations for the improvement of the Model 1867 Navy by the “St. Louis Commission,” (an Army Ordnance Board), a firing pin retractor and rotating extractor were added. The barrel was lengthened to 8″.

The grip frame was redesigned with a distinctive hump, offering better control when supported by the web of the hand. The front sight was changed to a long blade and mainspring power was transmitted to the hammer via a stirrup. It was chambered for the .50 centerfire pistol cartridge. Total production of the Army model is estimated at 5,000 units although the Remington Model 1891 Target and Model 1901 Target pistols continued to utilize the Model 1871 Army action.

The Model 1871 Army in the picture came with two barrels — the original barrel and a modern replacement barrel chambered not for the .50 Pistol cartridge, but for the .50 Carbine cartridge.

Pistol .50 Or Carbine .50?

If it sounds a bit odd, the only other Model 1871 Army regularly appearing at our range carries an original barrel re-chambered to .50 Carbine — a round originally developed for the Model 1867 .50-45 Navy Carbine made by Remington. It featured a shortened .50-70 case (1.35 rather than 1.75″) carrying a 400-gr. bullet backed by 45 (rather than 70) grains of powder.

So here you have two Model 1871s with carbine-length chambers. The question is why? My hunch is because the .50 Carbine case is so much easier to make than the .50 Pistol case from .50-70 brass. When you cut a .50-70 case down to pistol length (0.90), the case walls are so thick you can’t seat a 0.512–0.518 diameter bullet without thinning out the walls with a reamer!

In fact, the .50 Pistol cases I have made were from Starline’s .56-50 Spencer brass by Buffalo Arms Co., and the cases have been inside-reamed. Cutting a .50-70 case down to .50 Carbine length doesn’t require reaming. The other advantage of a carbine-length case is you can cobble up some ammo using inexpensive .50-70 dies.

Anyway, using a modeler’s cut-off saw from Harbor Freight, I slice off carbine length cases from .50-70 brass, trim them to length in a Forster big-bore trimmer, load them with a magnum primer and 30 grains of Alliant’s BlackMZ. I then seat a 300-gr. bullet from Buffalo Arms and send it downrange at 960 fps. This 30/300 combination is the original load formula for the .50 Pistol cartridge and it’s great fun! Lots of smoke, noise and recoil. It’s the smell of power! Plus, I can keep my shots within 2″ at 25 yards. Don’t ever pass up a Remington single shot pistol — they have too much character and a fascinating pedigree.