No Man's Land Is Ours!

British Scout/Snipers Armed With The Excellent Rifle,

No. 4 (T), Last And Best Of The Lee Enfields,

Were A Dominating Force in WWII

The 20X telescope (shown cased, top left) proved superb. The No. 4 Mk I (T)

was arguably the best of all WWII telescopic-sighted rifles. The 1943-vintage

map shown was assembled from prewar French, Belgian and Dutch maps. The

Fairbairn-Sykes Commando knife (3rd Pattern) often went along with the scout/snipers.

The Enfield .380 No. 2 Mk I* revolver usually didn’t. The binocular is a Kershaw 6X.

The Mk III compass is liquid damped with a radium dial. Scout/snipers were issued a

50-round bandolier (bottom right) and (not shown) a wristwatch, two grenades and

The lessons taught by the telescopic-sighted rifle in the trenches of WWI didn’t exactly lie fallow in the British military after WWI. But implementing them came down to the question of money. The same thing seemed to happen after every major conflict going back to the French & Indian War. Fortunately, the ideas and concepts stayed alive in the minds of serious men, even if they were unable to expend treasure on them.

The WWI sniper rifles fitted with woefully obsolete scopes were in stores. A small head start in telescopic sight development began in the mid ’30’s as pre-war arms designers worked on a scope and mount to be shared between the new BREN Light Machine Gun and the equally new infantry rifle — the “No. 1 Mk VI” soon evolving into the “No. 4 Mk I

The Kershaw 6X binocular (top left) fit inside any of the four pockets of the Denison

paratrooper smock favored by scout/snipers. A woolen scarf (top center) was handy in cold

weather and could be twisted into a headcover. Most snipers discarded the issued US M1907

sling for a BREN Gun sling. Longer than the Enfield sling, it was easier to use as a shooting

support and easier to clean. The metal water bottle (bottom right) was wrapped in wool for

insulation and has a cork stopper. A BREN Gun spare parts tin (center) was used to carry a

few cleaning patches, a spare extractor, extractor spring and screw, often a couple of grenade

pins and maybe hard candy. The Mark III compass spare rations and notebook (not shown)

would round things out.

The BREN Connection

Development of the No. 4 rifle and the BREN happened more or less concurrently. The BREN was envisioned for tasks beyond what was achievable. In addition to its infantry role, the big LMG was assigned missions such as anti-aircraft defense and to substitute for the tripod-mounted Vickers heavy machinegun. Ancillary gadgetry was needed to shoehorn the Bren into these roles. In addition, the BREN proved a complex, time-consuming arm to make, while the No. 4 rifle was designed for large-scale mass production. Its predecessor, the No. 1 Mk III, required skilled workmen and was also very time consuming to build (a hard lesson learned during WWI).

While one of the better ideas for the BREN was the telescopic sight, the mount’s design called for highly complicated machining of the receiver. After the tremendous losses of material at Dunkirk (especially BREN’s), the time-intensive extra machining steps for the optic were eliminated in the interests of boosting production, freeing up the scopes for the new No. 4 rifles.

Except there weren’t any… So many existing No. 1 Mk III rifles had been on hand, the No. 4 (accepted in the early 1930’s) hadn’t been put into production beyond a couple of thousand or so trial rifles built to fine-tune the manufacturing process. Britain declared war on September 3, 1939. In October the No. 4 finally got the green light with production authorized in Britain, Canada and America. The immediate need for a sniper rifle was satisfied by mounting the new scope to existing No. 4 trial rifles.

The No. 4 rifle proved far more amenable to telescopic sighting than contemporaries in use by friend and foe alike. The No. 4’s bolt handle — conveniently low already — required no modification to mount the scope low to the bore. The big, flat steel receiver was a perfect place to screw on scope bases, and the rear sight needed just its battle sight aperture removed to clear the scope’s ocular. The stock was given a simple screw-on cheekpiece to raise its comb. The fore-end received special attention and fitting. The action and trigger were smoothed and set for pull weight. The No. 4 (T) — the “T” is for “telescope” — earned a reputation for fine, consistent accuracy and the first 554 sniper rifles were completed by the end of 1942.

At least the selection of the new rifles for sniper conversion was simple. The factory sent the best-shooting ones after test firing for refinement.

Most — 23,177 — were completed by capable, custom rifle makers Holland & Holland, and our test rifle is one of those. Like most, it started life at BSA (Shirley) and went on to H&H. It is marked with H&H’s WWII code “S51” on the bottom of the stock just behind the pistol grip. Another 1,141 were made at Enfield and Long Branch, Canada, for a total of 24,318.

The scope mounting was far more complicated than a first look would indicate, since the scope-base pads were hand fitted to the receiver and matched to the scope and mount mechanically to ensure the assembly was optically centered to the rifle bore from the start. Downsides were a rifle weight of 12+ pounds, and the ridiculously complicated scope adjustments required a special tool and an additional set of hands to accomplish.

Tank-Tough Scope

The steel-tube telescopic sight, adopted as the No. 32 Mk I, was tank-tough. Magnification was 3X and it had a 19mm objective. The odd (even by 1940’s standards) left-hand windage drum was a hangover from the offset left-side mounting required by the top-feed magazine of the BREN.

While this new optic’s weight may seem trivial to the 24+ pound BREN, it adds 2 pounds, 3.6 ounces (including mount) to the 9-1/2-pound No. 4 rifle. The cast-iron mount and steel-bodied scope designed for the harsh abuse given by a machine gun were overkill for the rifle, and thus proved sturdy and dependable, giving long service.

A signature advantage British scout/snipers had over all other combatants was a

20X telescope. With it, spotters could see things the 6X binocular couldn’t and was

very useful in gathering intelligence as well as spotting targets. The brass body was

blackened, but the finish scratched off easily. The eyepiece (inset) is marked “TEL.

SCT. REGT. MK. IIs” on the top line, the middle has the B.G & Co. Ltd. logo for the

Broadhurst Clarkson & Company and the bottom line has the serial number “17263”

and “OS 126 G.A.” Beneath is the broad arrow acceptance mark.

Stalkers, Scouts, Snipers

Building the scout/sniper program was no mean feat, but didn’t have to start from scratch. Skilled Scottish Highland stalkers had been recruited in 1900 for the 2nd Boer War to act as scouts by Simon Joseph, 16th Lord Lovat. Known as the Lovat Scouts, Lord Lovat recruited Scottish “Ghillies” who were adept with the telescope, as well as skilled in fieldcraft in their capacity as game stalkers and managers. They were naturals as scouts, served ably in South Africa, then on several fronts in WWI. By WWII they were still in the establishment. Add the rifle with telescope and you had ready-made scout/snipers.

Recruits were also pulled from the rest of the army, and a program set up to train scout/snipers for the army in general. Recruits first proved they could shoot by making a 3-inch 100-yard group with the No. 4 (T) before being accepted for the sniper school. Training included the use of camouflage and cover, stalking, observation, and navigation among other skills necessary for survival and success — alone or in pairs — ahead of the frontlines.

In his book With British Snipers to the Reich, Capt. C. Shore defines their mission concisely:

“The general maxim to the sniper was that he should attain the standard of the highly skilled and cunning poacher…. The snipers’ task was invariably the same — to dominate No Man’s Land and the enemy forward defended localities when possible by killing Huns and making sure that the enemy’s movements were restricted as much as possible.” (1)

All Kitted Up

The rifle was packed in a compartmented, lockable wooden transit chest with twin leather handles. Inside was a 20X telescope, US M1907 leather sling (often replaced by a BREN sling), scope can with leather strap containing scope with scope caps, scope adjusting tool and a lens cloth. To fit in the transit chest, the sling on the rifle had to be removed.

The denim Denison paratrooper smock was very popular, since it was a pullover and amenable to a belly crawl. Its four deep pockets held everything needed for a day or two up front and were generous enough to hold binocs. The crotch flap with snap closures kept it from riding up in a backwards crawl. (It would prove equally useful today as a hunting shirt.) Also issued were a camo net to create a cowl or face veil and perhaps another wrapped around the rifle’s fore-end. Face paint was used as well as burlap head covers — anything to break up the man’s outline and help blend into the terrain.

The sniper and his partner/spotter were issued emergency rations, a compass, binocular, a wristwatch and a couple of grenades. Many carried a small BREN parts tin with a spare extractor, extractor spring, a couple of extra grenade pins, can opener and maybe gum or hard candy. Thus equipped, whether singly or in teams, the best scout/snipers could move close to and even behind enemy lines.

Snipers left school with 50 rounds of the ammo shooting best in their gun and it wasn’t uncommon for snipers to scrounge for ammo from the same lot once in the field. In addition, snipers also had 5 rounds of armor piercing (useful in putting a machinegun out of commission) and 5 rounds of tracer (although tracer was of little use since it instantly gave away the sniper’s position).

Unique to the British, the long 3-draw 20X “Tele Sct Regt MK.II.s” telescopes looked archaic, but proved more valuable than the relatively low-powered binocular in general use by all sides.

Being of the draw type, the telescope was more transportable than any other mid-20th century optic of high magnification. Old as the design was, it still had much to offer in performance vs. weight/size and the glass was very good. Perhaps more surprising is they stayed on into the 1970’s!

All the internals are held by wood blocks padded with horsehair and the ones for the

rifle have retaining strings. With the rifle out, the work begins. The scope, unpacked from

its green box, needs to be installed and its zero checked, and the rifle sling attached (contrary

to the instructions on the inside of the lid, the gun can’t be packed with the sling on). Our

intrepid scout/sniper is going to use a BREN sling, since they are easier to care for than the US M1907.

The chargers need to be stripped of cartridges to load the gun with the scope attached.

Our scout/sniper and his partner are likely off having tea with the BREN Gun team.

Both arms are connected in a way. The No. 4 (T) is fitted with the scope and mount

designed for the pounding of the BREN Gun. The complicated scope-mount dovetails

have been eliminated evidenced by the smooth left side of the receiver on this BREN

Mk Im, built by John Inglis in 1943. It has been rebuilt as a semi-auto rifle by Wise Lite Arms.

Both rifle and BREN had to be charged with ammo stripped off the clips and loaded singly

into their magazines.

Rifle and Scope

My test rifle was built at BSA Shirley in 1944 and sent to H&H for conversion to a No. 4 Mk I (T). Reliability is excellent, although I can cause a jam by not working the action briskly enough. Move the bolt slow and a cartridge nose occasionally pops up and jams just above the chamber at around 10 o’clock. The magazine, normally numbered to the rifle, isn’t. It’s probably not original to the gun and likely the culprit.

The trigger has been tuned evidenced by stoning across its face. It is a 2-stage military type and the first stage is 4 pounds. An additional 2 pounds of pressure breaks the trigger cleanly and consistently, for a cumulative total of 6 — near the upper limit of the pull-weight specification. (2)

The 3X No. 32 Mk II scope was made by William Watson & Son, one of eight firms making the No. 32, and bears Watson’s “Double W” trademark. The scope is still crisp and clear for its age. The signature improvement of this model is 1 MOA clicks rather than the Mk I’s 50-yards-per-click arrangement. The Mk I’s sliding sunshade is gone and this one has reproduction 2nd pattern scope caps made from the correct creased leather.

The elevation and windage adjustments of the Mk I and II are perhaps the clumsiest contraptions ever fielded. They require a special tool and a spare set of hands to zero. The goal using the tool is to adjust the crosshair so the turret caps are at “0” at 100 yards and the sniper can dial in his windage and distance.

To do this, the adjustment lock ring is loosened with the larger part of the combo spanner. Then the small spanner is turned to move the crosshair to the desired position while someone looks through the scope (no clicks) until the crosshair is aligned on a target at a specified distance. Then the locks are turned down, while another hand holds the top spanner rigidly in place. Armorers clamped the rifle firmly in a solid rest and bore-sighted on a target at a measured distance for reference. It is much easier to do today with a laser boresighter. But that “third hand” would still make the job easier.

This rifle’s scope mount and integral rings are of malleable “Whiteheart” cast iron by Rose Bros. Ironfounders and marked with their wartime code “JG.” The rings are bored, halved and numbered sequentially so they can stay together if removed. The mount often had the rifle’s serial number added in the postwar period and such is the case with ours.

The scope fits into this late-war square-cornered box and into the chest.

If the internal forward hole threaded to accept the scope attaching screw

looks large, it is. The box makers missed a critical dimension by a fraction,

and the holes weren’t spaced properly. So the forward hole was reamed larger

and only the rear is threaded. The leather sling with buckle and keepers reeved

through two steel loops on the bottom of the box and two on either side of the

lid. It makes opening the scope box burdensome. The scope adjusting tool is in

its spring clips. The gun’s serial number is stenciled on the lid.

Accuracy And Yardage

Part of the mythology of war is splendid shots by intrepid snipers on both sides. But the best shot can’t will the bullet to the target unless his equipment is capable of it. In the case of the No. 4 (T), the maker’s goal was a rifle capable of 2 MOA or so at 100 yards with good ammunition. This translates roughly to about 12 inches at 600 yards. Of course this doesn’t take wind into consideration and such accuracy is obtainable only under the best conditions.

Capt. Shore relates one such telling incident:

“Another day we found an unsuspecting Bosche about 600 yards away from us, and we could not get any closer to him. So we lined up three snipers together and got them to fire simultaneously hoping one of the bullets would hit. The hope was fulfilled!”

While visiting an American battalion in Italy, Shore tells of another experience:

“…I picked up with my telescope a whole bunch of Huns about 700 yards away on a mountain side who were digging like mad… We fired… and hit at least two of the Jerries… We missed a couple too, but the expression of utter surprise on their faces as I saw through my telescope at being sniped at by a single bullet from over 700 yards away was something I shall always remember.”

As a contrast, accuracy of the average infantry No. 4 rifle fired by a good shot using standard ammunition was at best 3 or 4 MOA at 100 yards, according to Shore.

The elevation turret on the No. 32 Mk II scope had range markings on the dial

corresponding to bullet drop of the Mk VII round. The scope adjustments are an >br>

overly complicated contraption impossible to zero without the tool (atop the OD tin).

A laser boresight and a target 25 yards away make this job almost doable today!

Field Expedient Solutions

Many snipers zeroed their guns for 400 yards. Doing so would assure a torso hit from 100 to 600 yards. He usually didn’t monkey with windage or elevation again in the field, but sometimes did!

Capt. Shore relates this bit of creativity:

“On this particular sector the slightest movement… invariably resulted in a fairly severe mortar ‘stonking’… the German observer; he was high in a tree, excellently camouflaged, but he had made the most elementary mistake of lighting a cigarette… A whispered conversation among the four [British] snipers followed as to the range… they could not agree… Three of the snipers set their sights at 250, 300 and 350 whilst the fourth sniper took the binoculars and kept them riveted on the prospective target… he coolly gave the three men the fire order; the three rifles ‘spoke as one’ and the Bosche came somersaulting to the ground.”

Most scout/snipers hated to remove the scopes from the rifles after they were zeroed. This created several new problems! There was no soft case available to sheath the rifle from weather with the scope attached and when one did appear, it wouldn’t accept the rifle with the scope on. Even the transit chest required the telescope be removed and placed into its metal box before going into the chest. The scope mounts “return to zero” better than many, but could still be off as much as 1 MOA.

Reluctance to remove the scope raised a maintenance problem, too. The bolt couldn’t be removed for cleaning with the scope attached, since the rear sight (under the scope) had to be raised to clear the bolt. This led to a “field” modification by company armorers who relieved the underneath of the rear sight enough so the bolt could be withdrawn from the rear with the sight folded.

Since the majority of cleaning was done with a pull through, this wasn’t a big problem, but being able to pull a bolt has many advantages. Our test rifle hasn’t had this modification.

The Enfield No. 4 (T) served as a sniper rifle long after WWII while the rest of the army was using the L1A1 (FAL) in 7.62x51mm. Finally, in the mid-1960’s, experiments began on converting the No. 4 Enfield into a sniper in 7.62. These exertions were successful and the L42A1 sniper served into the 1990’s. Its scope was a late WWII No. 32 Mk III, featuring improvements solving the majority of complaints about the adjustments. The kit included the old 20X 3-draw telescope — just at home with Nelson at Trafalgar as on the modern battlefield.

The scout/sniper concept stayed this time and is an integral part of the British army today. The Lee Enfield No. 4 Mk I (T) served well for 30+ years, and few rifles can boast such an honored legacy of service in so important a role.

The Short Magazine Lee Enfield No. 1 Mk III (top, made in Australia at Lithgow),

served Britain well during two world wars. A complicated arm to make, Mk III was

replaced (theoretically at least) by an arm designed from the start to be much easier

to mass produce — the No. 4 Mk I (bottom). Adopted in the early 1930’s, the No. 4

didn’t enter production until 1939. Not as smooth as its predecessor, it shot better

if fitted with good barrels, something not always possible as the war progressed and

standards were relaxed.

Rifle & Cartridge

The No. 4 rifle was the final development and last of the storied rifles first designed by James Paris Lee in the latter half of the mid 1870s. Despite attempts prior to WWI and WWII to modernize the cartridge, the No. 4 (perhaps wisely) was chambered for the long serving, if archaic, rimmed .303 British.

The rifle itself is simple and intuitive to use. Open the bolt and load 10 cartridges loosely or via two chargers. In closing the bolt, you’ll feel the spring pressure as the striker is cocked. This feature gives the Enfield a fast, smooth-cycling action. Rotate the safety lever on the left side of the action back towards you to lock the bolt. To fire, simply take aim, rotate the safety forward with your right thumb and squeeze the trigger. In the event of a misfire, the striker can be reset by grasping the cocking piece and giving it a yank. The striker has two positions, with the first an alternate safety position, and the second the firing position. This first position is not a practical safety, since a loud snick occurs as the striker is drawn to full cock, while the safety is very quiet going on or off.

Disassembly is simple. Raise the rear sight, depress the little catch on the right side of the action, and pull the bolt head over it. (This latch engages a slot in the bolt head to keep it in the receiver.) Lift the bolt head upright and withdraw the bolt. You can now clean from the breech. To assemble, push in the bolt, rotate over the head, depress the latch and push the bolt home.

The Enfield’s one disadvantage in the iron sight category is no windage adjustment other than drifting the front sight. The backsight is finely made and offers positive screw adjustable elevation. It was perhaps too finely made and towards the end of WWII, simpler backsights appeared, one as simple as a 2-aperture flip sight, the other replacing the screw-driven vernier with a simple spring catch for elevation adjustment.

All sniper rifles were fitted with the best quality vernier backsight with its battle aperture ground off. Working back, the buttplate has a trap held closed by a spring. Inside, an oiler and pull-through cleaner are kept. The walnut stock is oil finished, and the action, barrel and magazine evenly blued. Many of the other small parts are painted with Suncorite.

In general, the No. 4 suffers from a bad reputation caused by wartime relaxation of standards leading to wide variation in barrel bore-and-groove dimensions, bad magazine springs and other niggling defects. Properly built, the rifle shoots well, is reliable, durable and easy to maintain. A key attribute is the barrel is heavier than the Mk III and good ones shoot well. The action when new isn’t nearly as smooth as the Mk III — another gripe — especially among veterans teethed on the older rifle.

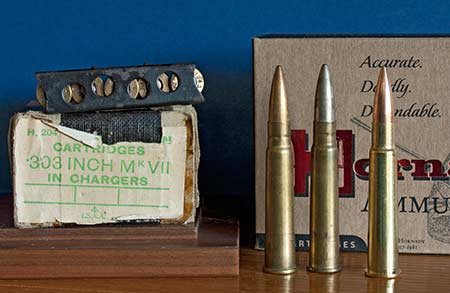

British Mk VII ammo served all during WWII, sometimes issued in boxes of 20 with

four 5-round chargers. The chargers were loaded with the rims overlapping with

the rims of the 1st, 3rd and 5th rounds at the back of the charger. The 174-grain

FMJBT of the Mk VII round (middle left) had three stab crimps to secure it in the

Berdan-style cases with corrosive primers. Some were loaded with cupro-nickel

bullets (center), others of more modern bullet jacket material. The modern Hornady

round (right) has non-corrosive Boxer primers in premium brass and HPBT bullets.

Black Powder To Smokeless

Originally using a compressed black powder charge, the .303 British cartridge underwent improvements throughout its service. The ballistics of the smokeless Mk VII load was perfectly adequate for the WWII battlefield, delivering a 174-grain boattail bullet at 2,440 fps. A real detraction was the cartridge’s antiquated rim. It was a nuisance in both magazine rifles and machine guns.

Ammunition was issued in 5-round chargers in boxes of 20 or bandoliers of 50 rounds. With the scope attached, charger loading is impossible, so 10 cartridges are thumbed singly into the magazine. When loading, make sure the rim of the next round is in front of the preceding one. The .303 can jam if the rim of the cartridge feeding is behind the one below it in the magazine.

Shooting Results

If 3-shot groups were the rule, I’d be crowing, but I fired 5-shot groups, and at least they were in spec for the rifle. The curved, smooth buttplate slips around on the shoulder, and probably didn’t help, since almost all of the 5-shot groups were nice triples and nice pairs, or two pairs with a single. Much as I tried to keep the butt squarely on my shoulder, the groups say I wasn’t always successful!

The best factory load was Hornady Vintage Match, which delivered a 1-7/8-inch 100-yard group with 3 shots routinely in 1/2 or 3/4 inch. Other loads tried were a 180-grain soft-point hunting load from Winchester, one from Precision Cartridge, and a “no longer imported” South African PMP load, both with 174-grain FMJ’s. Most groups were in 2-1/2-inch range.

I hadn’t handloaded for the .303 in a decade, but finding some Alliant Rl-15 changed my mind. It was rewarding to beat the Hornady factory ammo for a change and 39.0 grains of Rl-15 under a Sierra 174-grain BTHP delivered a 5-shot 100-yard group of 1-3/4 inches. The dies were RCBS and the primers Winchester Large Rifle in Winchester Brass. ”

Cases were very difficult to resize unless the necks were lubed inside, and had to be trimmed after two loadings. Other than that, there were no surprises until I got to the range. There, having worked up the load in 0.5-grain increments, the difference up 0.5 and down 0.5 grains on either side of 39.0 translated into 1 or 1-1/2 inch larger groups at 100 yards.

Sources

1) With British Snipers to the Reich, Capt. C. Shore,

©1948, Thomas G. Samworth, hardcover, illustrated, OP

2) An Armourer’s Perspective: .303 No. 4 (T) Sniper Rifle and the Holland & Holland Connection,

by Peter Laidler with Ian Skennerton, ©1993,Ian Skennerton & Peter Laidler, IDSA Books, IDSA Books, P.O. Box 36114, Cincinnati, OH 45236, (513) 985-9112, www.idsabooks.com

3) The Lee Enfield, A Century of Lee-Metford & Lee-Enfield Rifles & Carbines by Ian Skennerton, ©2008 Ian Skennerton, Arms & Militaria Press, 1638 NE Beverly Drive, Grants Pass, OR 97526, (541) 659-0373, www.skennerton.com

4) The Bren Gun Saga by Thomas Dugelby, revised and expanded edition edited by R. Blake Stevens,

©1999, OP, Collector Grade Publications Inc., P.O. Box 1046, Cobourg, Ontario, Canada K9A 4W5, (905) 342-3434, www.collectorgrade.com

More Information:

APEX Gun Parts

BRP

Buymilsurp.com

Hornady

International Military Antiques

Numrich Gun Parts

Military Antiques & Museum

www.militaryantiquesmuseum.com

Jon Moore Leather

Sierra Bullets

What Price Glory

Wolff Springs

World War Supply