365

A Border Tale

Sometimes one good man is all it takes ...

It never fails—not for me, anyway. You make a multi-state move, a couple thousand miles, and you can’t find the boots you wore one day before leaving, but you find a pair of dog-chewed moccasins you’re certain you had tossed out years ago. This time I also found a battered Moleskine notebook marked “Border Stories.” I had searched for it several times in the past with no success and thought it was lost forever.

The words “border” and “frontier” have always drawn me, fascinated me, perhaps because I grew up in the Pacific where borders were pretty meaningless, and what the heck would a frontier be? So I read, ravenously, all the tales I could find of wild frontiers and embattled borders, the lonelier and more disputed the better.

That only whetted my appetite for more and later, I saw as many of them as I could, like a few parts of the Iron Curtain were more like shredded gauze. Another border where two bashful teenage boys with AK-47’s and their fearsome mother secured the frontier—Perhaps stories for another time. But the book fell open to this one: a once-wild border, and the man who held it.

The Border Guard

South America: My training liaison assignment was complete. The capital’s security chief, a silver-haired, very courtly general, kindly arranged me a visit to the furthest-flung outpost of their frontier. “If,” he said, “You will execute a small official act, and perform a personal favor for me.” He produced a stout canvas case and an envelope, explaining they were for “the border guard, with my compliments.” I assumed he meant the border guard contingent.

“No,” he smiled, “One man. I am sure you will treat him with respect. Please address him as sergeant.” Officially, my mission was to “inspect the condition of the border bridge,” and unofficially, to discretely assess the sergeant’s health. Then, he said, “You will please report personally, confidentially and only to my son”—the border district commander, a colonel. Only, huh?

Confidentially? That gave me pause, but I was a young pup, and in my imagination I was already there.

Before this trip, I had read about this desolate stretch of border; the battles fought over it, the bandits who had terrorized it, the blood spilled in its rocky riverbeds. La frontera!

A long day and night of teeth-jarring travel later I stood in a tiny village, presenting my letter of authority to a short, whip-thin man seemingly chipped from flint. Age? You’d have to carbon-date him. His hair was thick and gray, but his moustache and long, curling eyelashes were jet black; deceptively youthful on his time-fissured face. His uniform jacket was faded but neat, the leather bill of his cap and disintegrating boots brushed and blacked, his spine and stature straight and true. He was obviously very tense. Then I gave him the general’s envelope and as he slowly, with great difficulty, read the message inside and neared the end, he visibly relaxed and beamed with an oversized grin.

“Most excellent!” he cried. “Bueno! We are to be friends most informal!”—and he whacked me on the shoulder with a horn-hard hand. “Oh, the General! What a good boy—and a fine man!” Good boy? He excused himself and hobbled away, his boots clearly killin’ him.

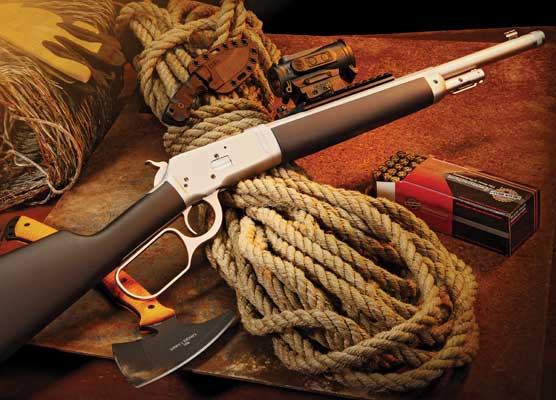

When he returned, he moved like a comfortable panther in loose pants and blouse and blown-out gum-soled sandals. Opening the canvas case in a circle of excited villagers, he pulled out ammunition and a wrapped parcel, putting them aside. The rest was tins of jam, potted beef and other delicacies, a sack of coins and a big bag of candy—all distributed amid much joy. So, our “most informal friendship” began among laughing children and happy parents.

The sergeant’s parcel was a new pair of those gum-soled sandals with short lengths of rope embedded in the rubber. He held them to his nose, sniffing their newness, and his eyes glistened wet. “My General,” he choked.

The next morning I inspected the bridge, an old wooden trestle type. It was in good shape—especially for a bridge to nowhere. It began at the foot of the village, spanned a narrow tributary and ended 50 meters from another deep, eroded channel. I looked at the sergeant, puzzled. He only nodded and turned away.

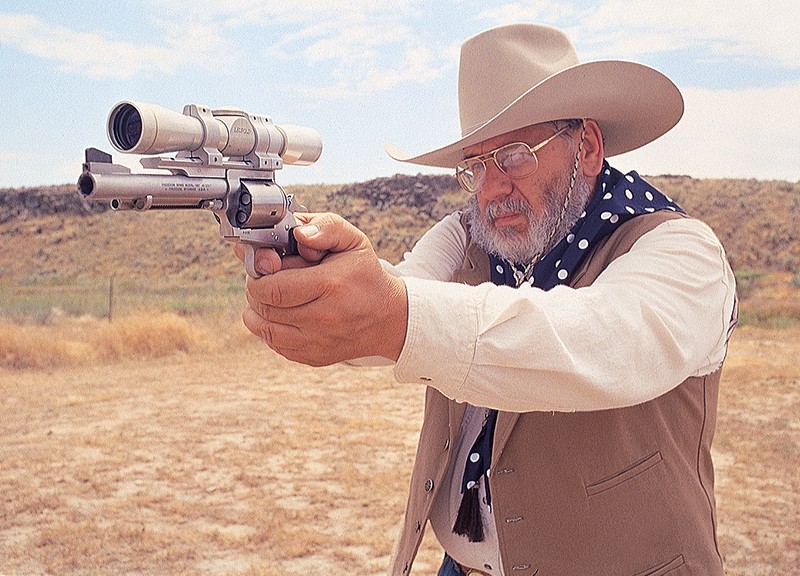

I was well trained and combat-experienced, but what followed was a consummate post-graduate course in defensive patrolling. The sergeant’s area of responsibility spanned about 40 square miles of wild, jumbled badlands. Running along the North-South bluffs over a once-mighty river, now several trickles and small streams of clear, sweet water, he had perhaps 50 observation points from which he could scan about 20 avenues of possible transit.

The first thing I noticed about them was that every single observation point could be approached and exited in complete defilade, shielded from view. Then I learned his path selections were also dictated by the direction of convective wind gusts. He was extremely attuned to creating visible dust plumes, and every time, if he raised a little dust, it dispersed unseen, in defilade—otherwise, he would detour a mile or more via other carefully chosen routes. Also, he had numerous firing points to cover various close approaches, and none were his primary viewing points.

He knew the nominal speed at which men on foot, on horseback, or in vehicles might travel from any one point of transit to any other—and where they were most vulnerable to a hidden rifleman. His daily route varied in daylight and darkness, from 10 to maybe 15 miles, and he owned every smooth, silent step. No man alive knew those badlands as he did, or could be a deadlier foe in them.

The border had been uncontested, quiet, for over 20 years, but you’d never know it from his tactics and the intensity of his watchfulness. I asked what would happen if his neighbors invaded in force. Tiny fires glittered in his eyes. He explained, “they would be delayed, demoralized, possibly stopped; plenty of time for warning.” I didn’t doubt that for a second. I asked about bandits. His fingers tightened on his rifle.

“Here—no more,” he said. I didn’t press it. His eyes spoke volumes. We parted as friends.

The Sergeant’s Story

In the district headquarters I met the colonel, a striking guy with an Errol Flynn moustache; a younger version of his father. In a private room over coffee and brandy, I made my report, and he filled in the blanks. As an orphaned lad the border guard became a cavalry company’s stable boy. When the colonel’s father arrived as a newly frocked lieutenant, that grown-up boy was already a veteran sergeant. “The kind of sergeant armies are built on, or die from the lack of,” he said.

For many years they rode and fought on the frontier together. When the horse cavalry transitioned to vehicles, they transferred to the infantry together. When the colonel himself became a lieutenant, the sergeant was the loyal linchpin of his first command.

“His only family was the army; his only life, defending the country. What becomes of a man like that when he is too old to continue military service? The civil servant post there is for a bridgekeeper, but that would not be fitting. So, my father and I, we make him the frontier border guard—a nonexistent position. At his request, his army pension and his bridgekeeper pay, all of it, goes as credits to the market at the railhead. This provides for the village and they provide for him; food, housing and respect. He wants little, and he wants for nothing. My family contributes, and sends gifts. The bridge means nothing; it need only exist so we may continue this charade.”

“And,” he smiled, “Would you wish to invade his ground?”

Connor OUT