THE BRITISH ENFIELD NO. 2 .38

HANDGUNS OF WWII PART 3

Part 3 Of A 13-Part Series

A statement I’ll make about the British Enfield No. 2 Mk I .38 revolver is one I’m not willing to make about any other British weapons of World War II. That is, “It’s delightful.” By military handgun standards it is almost petite, but unfortunately so is its caliber. We’ll get to that point soon.

With a 5″ barrel and serrated (not checkered) two piece walnut grips, it weighs just a pound and three quarters. Think about that: 28 ounces is a weight designers of many modern handguns using synthetics would wish upon their brainstorms. According to the book “MILITARY HANDGUNS OF TWO WORLD WARS” by John Walter, the Brits adopted the Enfield No. 2 in June 1932. For nearly 50 years prior to that their issue sidearms had been one “mark” or another of the basic Webley .455, with the last being the Mk VI adopted in 1916. Also, according to Walter’s book, the reason for reducing caliber from .455 to .38 was that recruits had trouble handling the recoil of the larger round.

That seems odd to us American handgunners because the .455 round fired a 265 grain bullet at only 600 fps. It’s an extremely mild round and shouldn’t give beginners any trouble. However, I must stick this in as a jab at the British. In his new book “WORLD WAR II: A MILITARY HISTORY”, author Gordon Corrigan quotes one general as saying after the British Army was kicked out of Norway by the Germans in 1940, that their soldiers were “effeminate.” I’m just quoting here!

Anyway the new .38 cartridge the British adopted with the Enfield No. 2 was at first called the .380 Revolver Mk I. It used a 200 grain lead alloy bullet at a nominal speed of 550 fps. British ordnance officers insisted the .38/200, as it’s commonly called, had exactly the same stopping power as their .455 Mk VI with a 265 grain bullet at 620 fps (Figures taken from “MILITARY SMALL ARMS OF THE 20TH CENTURY: 7th EDITION” by Ian V. Hogg and John S. Weeks). Of course by the laws of physics that was impossible. Also the term “new” should not be applied to the Brit’s .38. Its case is nothing more than the .38 Smith & Wesson’s, which that handgun manufacturer introduced circa 1875.

Get The Lead Out

The British started World War II with their Enfield No. 2 revolvers stoked with that lead bullet load, and of course the Germans captured oodles of them when they kicked the British army off the continent of Europe in 1940. Since lead alloy bullets were proscribed by the “laws of civilized” warfare, the Germans informed the Brits that anyone henceforth captured with lead bullets in their ammunition would be executed. This caused the Brits to come up with another version called the .380 Mark II. It used a 178 grain full metal jacketed (FMJ) bullet at 600 fps or thereabouts.

Let’s go back to my sample of an Enfield No. 2 revolver and why I think it’s delightful. Its basic design is top break, actuated by a thumb latch on the left side of the frame. As its barrel is moved downward, the ejector is cammed upward extracting all rounds, fired or unfired, out of all six chambers. To the best of my knowledge the Brits never developed a speed loader for their top-break revolvers so presumably six more loads were inserted singly.

The Enfield No. 2 Mk I is a double action, meaning it can be fired by pulling the trigger or cocking the hammer and then pulling the trigger. A version designated No. 2 Mk I* was developed with no hammer spur and could only be fired in the double action mode. This version was issued to crews of tanks and armored cars because it was felt the spur on the hammer of the prior version could hang up when getting in or out of vehicles.

That double action trigger pull is why I consider the Enfield No. 2 Mk I to be such a delight. The trigger moves less than three-quarters of an inch to fire double action. Combine that trigger pull with the extremely mild recoil of the .38 with either 178 or 200 grain bullets and directing a bullet to the target is easy.

Even Good Sights

The sights should be mentioned at this point. For their era, the Enfield No. 2 Mk I’s sights are good: meaning wide and visible. The front is about 3/16″ wide, tall and square. The rear is a likewise-wide and square notch cut into the barrel latch. A plus is the front sight sets in a groove in a stud forged integral with the barrel and is secured by a small screw. It’s changeable for height, meaning individual revolvers can be zeroed at least for elevation. Windage is not adjustable.

My particular specimen is marked RAF and dated 1936. RAF stands for Royal Air Force and this revolver presumably was issued to a pilot or air crew of bombers. Since it shows none of the ravages of weather its likely it was carried a bit and never used outdoors.

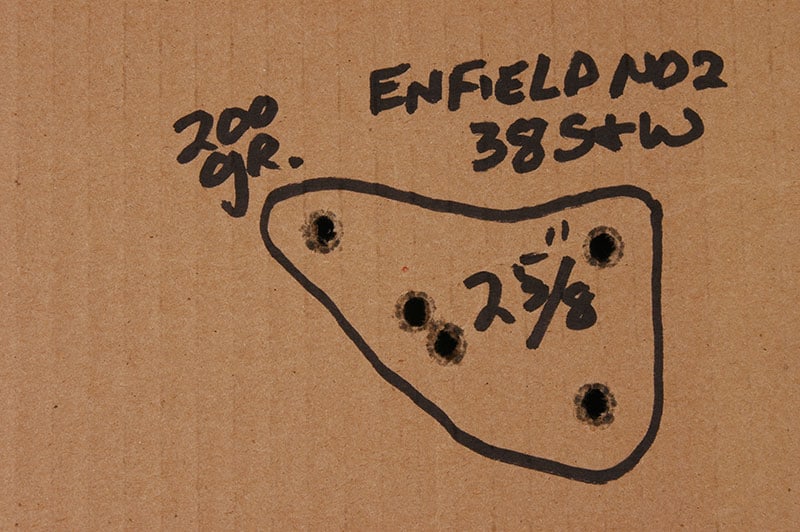

Having been made prior to World War II’s outbreak I also presume its front sight was the one used for the 200 grain Mk I .38 loading. That’s because it hits right to point of aim with my handload duplicating that one. It’s Lyman’s bullet mould number 358430, 200 grains of 1-20 tin to lead alloy, over 1.8 grains of Bullseye powder in new .38 S&W brass manufactured by Starline. Velocity of my load was clocked at 612 fps.

I enjoy shooting my Enfield No. 2 Mk, I but I wouldn’t want to tackle an adversary more ferocious than a ground squirrel with that .38/200 load!

Click here to links to all the 13-part on-line series of Handguns Of World War 2 articles.