The RPK Squad

An Underappreciated Masterpiece

It’s easy to write off the RPK as an uninspired solution to a thorny tactical problem. The action is standard Kalashnikov, the barrel is fixed and the magazine feed limits its capacity to 75 rounds. Some might say this plants the design firmly in the realm of interesting history but little more. In light of current doctrinal developments, however, the RPK might be deserving of greater respect.

The center of gravity of any dismounted infantry formation is its automatic weapons. For all their well-documented moral failings, the Nazis were arguably the most capable military innovators in all of human history. When the rest of the planet seemed mired in the doctrinal dogma of stalemate so refined in the First War to End All Wars, the Germans embraced mobility.

Their revolutionary MG34 belt-fed General Purpose Machine Gun (GPMG) provided individual small unit infantry commanders with a reliable source of high-volume fire capable of moving with the dismounts. Built more like a sewing machine than a combat tool, the MG34 was eventually supplemented by the comparably revolutionary MG42.

The MG42 was the first truly advanced Infantry weapon to be optimized for mass production. Comprised predominantly of industrial stampings and throwing those big, heavy 8mm Mauser rounds as fast as a MAC10 submachine gun, itself an impressive little bullet hose, the MG42 earned the respectful sobriquet “Hitler’s Zipper” from Allied grunts on the receiving end. For the first time in the history of warfare, the Germans built their infantry units around the nucleus of a truly portable machine gun.

The rest of the world followed suit in short order. The British had their Bren. The Americans had their BAR and, to a lesser degree, the bodged-together belt-fed 1919A6. The Russians used the pan-fed DP machine gun. Warfare would never again be the same.

The Soviet RPD seemed like an inspired solution. Firing the outstanding M43 7.62x39mm intermediate cartridge from non-disintegrating 50-round belts, the open-bolt RPD was lightweight and maneuverable. The RPD still had a fixed barrel and was therefore not amenable to the sustained fire role but it carried 100 rounds on board when fully loaded. The RPD is a bit environmentally sensitive and it is hard to run in a hurry. For some reason the top cover does not pivot up much past 45 degrees and the top cover release latch is hard to manipulate even when your hands are dry and nobody is shooting at you. Clearing stoppages can therefore be a chore even under peaceful circumstances.

There’s a universally respected infantry axiom: The only thing better than having a gun easy to clear is having a gun that just never stops — enter the RPK.

Pedigree

The RPD’s replacement was the Ruchnoi Pulemet Kalashnikova or RPK. Adopted in the early 60’s, the RPK is basically an AKM on steroids. The RPK utilizes the same bolt and bolt carrier as the AKM but incorporates a longer, heavier barrel, a more robust receiver, a clubfoot buttstock and a bipod. The buttstock has a spring-loaded trap for an oil bottle. The RPK tips the scales at about 12 lbs. unloaded. It feeds from standard 30-round AK box magazines, extended 40-round boxes or 75-round spring-driven drums. It also lacks a quick-change barrel.

Michael Timofeyovich Kalashnikov purportedly devised the action for the assault rifle bearing his name while recovering from wounds incurred during the Battle of Bryansk in World War II. While his story has the feel of something possibly streamlined a bit by communist propaganda editors, it’s universally accepted he indeed designed the gun, and it subsequently shaped the world.

There are more than 100 million copies in circulation and the number grows daily. Hardly the most accurate or attractive infantry weapon, the AK sets the absolute standard for reliability among military firearms. I have actually had a stoppage or two over the years with AK rifles but it requires the most egregious neglect and abuse to incite them.

The original AK sported a stamped steel receiver that was soon replaced by a functionally indestructible forged steel version. In the mid-1950’s the AKM reappeared with a now-perfected stamped receiver rectifying the original’s shortcomings and became the most widely distributed variant. In the early 1970’s the AK was reimagined in 5.45x39mm as the AK74, versions of which are still general issue in Russian military units today. Along the way there were chopped-down AKSU submachine gun versions as well as a heavily modified belt-fed variant issued as the PK series of medium machine guns. Concurrently the basic system was highly modified to form the SVD sniper rifle, actually more of a Designated Marksman Rifle in Western parlance, and the RPK SquadAutomatic Weapon.

The much-maligned ranch gate safety is loud, clunky and cumbersome but still works just fine. All the way down is semi-auto. All the way up is safe and blocks the bolt track to help keep the action clean. The middle position is full- auto.

The sights function identically to those of the AK and are optimistically adjustable out to 1,000 meters. The RPK incorporates a unique micrometer feature to the rear sight assembly allowing for precise adjustments of windage. This device is not included on typical AK rifles. The bipod secures in the stowed position via a spring steel clip pinching the legs around the cleaning rod and the legs are typically adjustable for command height. Aside from the buttstock and bipod, on the user level the RPK is just a big Kalashnikov. Even a child could use it and many have.

AK box magazines are interchangeable between the AK and RPK. There have been dozens of magazine designs, most of which are heavy, bulky, indestructible and reliable as a tire tool. The 40-round versions are really too long to be used readily from the prone but do provide a lot of firepower while on the move. The same box magazine runs like a champ on the smaller AK rifle and is typically in great demand in theater for its perceived combat advantage.

Drum magazines come in two broad flavors. One is sealed and loads just like a big box magazine one round at a time from the top. The other has a swing-open steel back and winds with a permanently attached key. Though the swing-open version rattles badly, it is infinitely easier to load and can be stored indefinitely without spring tension.

The RPK is still a bear to carry for long distances but it is a huge improvement over an M60 or PKM. When slung over the right shoulder the charging handle is clear. Having a charging handle abrading your sensitive anatomy during a long forced march will quickly exhaust even the hardiest sense of humor. The standard AK sling employed by the RPK is really too short but it mounts on the left side as it should.

Doctrinal Revelations

Back on this side of the pond, the belt-fed M249 SAW has soldiered on reliably in US service since the mid-’80’s. Designed and originally produced in Belgium, the M249 has nominally retained the capacity to feed from M16 box magazines as well as standard 200-round belts. The M249 is also available in a remarkably compact Para version with collapsible buttstocks in two varieties and a short barrel. Barrels are readily replaceable in the field without tools, and the gun fires from the open bolt. Despite these desirable design features, the USMC still reached out for an entirely different weapon to supplement the time-proven SAW.

The HK M27 Infantry Automatic Rifle is essentially a heavy-barreled M16 with all the bells and whistles. Firing from a closed bolt and utilizing standard M16 box magazines, the M27 fills a need the Jarheads recognized for a portable weapon offering the same degree of first-shot reliability exhibited by the M4 while including a modest sustained-fire capability. The Marines claimed the belt-fed SAW was not sufficiently reliable to arm the point man on breaching teams. The M27, which by all accounts has been well received by Information Age Marines in a combat theater, bears an eerie resemblance to the magazine-fed RPK of a previous generation.

Making Noise

The RPK is my hands-down favorite machine gun. It weighs less than half what a belt-fed GPMG (like the M60 or M240) does and employs a manual of arms all but stupid proof. There is no fumbling with floppy ammunition belts or top covers with the commensurate concerns for mud and fouling. Just rock a magazine in place, run the bolt and go.

The mid-sized M43 cartridge hits hard downrange without feeling like a boat anchor when carried in modest volume. The M43 round was designed more than 60 years ago by a totalitarian regime peopled predominantly by peasants. Nowadays, the flower of Western engineering is producing revolutionary rounds like the .300 AAC, bearing striking similarity to this original mid-range load as well as the World War II-era German 7.92x33mm Kurz. The 75-round drum magazines protrude no farther underneath the rifle than a standard 30-round box and last a good while with proper trigger discipline.

Most RPK’s lack a flash suppressor but the long barrel is sufficient to burn most of the powder so it doesn’t produce an inordinate muzzle flash at night. The barrel is threaded for the standard AKM slanted compensator but this device does nothing for muzzle flash. There is typically no provision for an optical sight.

When run in semi-auto, the long heavy barrel, bipod and clubfoot buttstock of the RPK make for a fairly accurate package at reasonable distances. The action on the gun is sloppy and it will never be a tackdriver but in practical use it is easy to lob half a dozen rounds at a target and typically connect as far out as physics might allow. The sights are terribly 1940’s, but they won’t break and they allow enough adjustment to suit the typical, semi-literate users of the gun. One of the front sight ears on my gun got bent once when I got a little frisky with it on the range. Thirty seconds with a pair of vise-grip pliers fixed it right up.

I find rate of fire is the single greatest determinant of downrange effectiveness for a man-portable machine gun. When locked in a tripod or fired from a vehicle, fast is great. When run from the hip, shoulder, or prone; however, slower seems better. The MG42 in its original form runs at about 1,200 rounds per minute. The MG34 and RPD cycle at about 900 rpm. The RPK chugs at about 650 rpm or so and fits my ballistic personality perfectly.

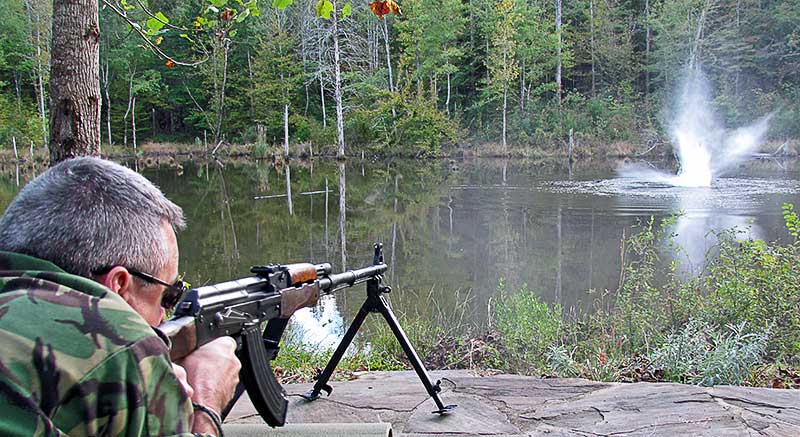

The RPK is light enough to be fired from the shoulder. As with all automatic weapons, the operator needs to lean into the gun and let gravity help tame the recoil. With a little practice short bursts can shred a man-sized target at 100 meters all day long.

Firing the RPK from the hip is positively recreational. With a properly adjusted sling the gun hangs naturally and the long, heavy barrel keeps the muzzle down. The 40 and 75-round magazines feed the beast amply enough to allow the operator to walk rounds into a target at reasonable ranges. The geometry of the RPK strikes a nice balance between portability and control. Marching fire, something I was taught but doubt is much in vogue any more, is easy with the RPK. Considering this technique involves a large group of exposed troops shooting monotonously in the general direction of the enemy during an advance it is likely, like me, justifiably obsolete.

From the prone off the bipod the RPK suffers from its magazine feed system. The bipod swivels from side to side but does not pivot. As such, engaging traversing targets requires the bipod feet to slide about. The 40-round magazine transforms a prone shooting position into an exercise in frustration unless firing downward from an elevated vantage. A tactical option is always to dig out a depression underneath the gun to accommodate the magazine.

Once an appropriate position is prepared; however, engaging distant targets off the bipod is an intuitive exercise. The nose heavy weight of the gun keeps burst dispersion in check and the sedate rate of fire maximizes ammunition efficiency. By contrast, an MG42 will eat a 50-round belt in a flash and jump all over the place in the absence of proper technique.

The barrel on the RPK heats up fast and there is little to be done about it. The bolt remains closed both loaded and empty and the lack of a quick-change barrel feature means an overheated gun must either be left alone for a while or dunked in water to cool it off. In the final analysis, the RPK is clearly a Squad Automatic Weapon optimized for supporting fire on the move rather than a sustained fire platform to be employed for long periods from fixed positions.

Grand Scheme

British Tommies in World War II all carried a couple of Bren magazines to feed their organic Bren gun. In WWII and Korea stories abound of combat action orbiting around a well-fed Browning Automatic Rifle. When the BAR went down or went dry the position could soon become untenable. Despite the fact its rate of fire was slow and it launched the same cartridges as individual grunts’ Garands, the reassuring chug from the BAR was the center of gravity for the Infantry unit. The same could be said of the M60 in Vietnam.

In conventional Infantry units, the fact the RPK fed the same ammunition from the same magazines as individual riflemen was an immeasurable boon. This simple fact combined with the impeccably reliable Kalashnikov action ensured a steady source of automatic fire in both the assault and defense. An interesting fact is that the RPK has seldom been employed in conventional Infantry formations.

Thankfully for all of us, the Cold War never warmed up so most Kalashnikov weapons have been employed in insurgencies, terrorist actions and brushfire wars for the past half-century or more. In many of these cases the bulk of the RPK was a detriment to the concealability and mobility required of weapons employed in asymmetric warfare. However, the salient features of the RPK still made it a robust and effective tool for both good and ill.

Sometimes appearances can be deceiving and the best SAW might not be belt fed or even brand new. In the Information Age we find ourselves rediscovering the value of fat, heavy bullets fired from a robust, simple mechanism. Among all the world’s military arms, few can compete with the 50-year-old RPK for reliability, flexibility and downrange thump.