Now we’ve covered the authenticity part so we’ll hit the easy-shooting part of the equation: factory ammo for the ’73 centerfires is common and so are bullet molds, reloading dies and commercially cast bullets. Careful handloaders can use original Winchester ’73’s after having them checked for safety while replica 1873’s have been coming over from Italy for nearly as long as the originals were made. Browning is now importing them from Japan and — having legal rights to do so — can stamp them Winchester again. Between the Italians and Japanese we have had ’73’s made for .22 LR, .38 Special/.357 Magnum, .38-40, .44 Special, .44-40 and .45 Colt, although not all those calibers are still available.

Talk about easy shooting! I’ve experienced them all except for the .22 LR and have been using a Cimarron/Uberti ’73 in Sporting Rifle configuration with checkering and pistol grip stock for over 23 years. Two of the newer Japanese ’73’s are here with me right now. Both have 20" barrels: one is a Short Rifle, the other a Saddle Ring Carbine. The SR is .44-40, but finally willing to give a modern caliber a chance, I ordered the SRC in .38/.357. I have been impressed with the new Japanese made ’73’s. They come out of the box with actions as smooth as if a gifted gunsmith had worked on them.

Frontier Firepower

A smokin’ piece of history: Winchester’s Model 1873

Winchester billed their Model 1873 lever gun as “The Rifle that Won the West.” It didn’t, at least not all by itself but it did win my West. For 20 years I was an avid player in the Cowboy Action game and after the first year, my rifle was always a Winchester ’73. I’ve shot deer with them and metallic silhouettes too. Mine have experienced both black powder and smokeless ammunition but I’ve always been careful to abide by the proper caveats for antique metal and a “not-all-that-strong-a-locking-design.”

Love At First Lever

What tripped my trigger about ’73’s? The answer is simple: they combine historical authenticity with easy shooting. I’ve owned many originals in all three factory calibers and still have five.

The lever guns most commonly used during the Plains Indian Wars of the 1860s/1870s were from Spencer and Henry along with the Winchester Model 1866. However, Winchester did get their Model 1873 out just in time for some of the greatest fights of the conflict. Archaeologists have proven no fewer than eight ’73 .44’s were in Sioux or Cheyenne hands during the battle of Little Bighorn. The first ’73 chambering was also Winchester’s very first brass-cased, reloadable cartridge. They called it the .44 Winchester Centerfire or .44 WCF but we call it .44-40 nowadays and it’s my favorite of all Old West rounds.

In 1879 Winchester followed the initial chambering with .38 WCF (.38-40), in 1882 with .32 WCF (.32-20) and shortly thereafter with .22 Short and .22 Long. Rifles for the latter two cartridges are instantly recognizable by the lack of a loading port on receivers’ right sides. There can be no doubt Winchester hit a home run with the Model 1873 — the company produced almost three-quarters of a million of them between introduction and 1923.

Styles, Configurations

Back 100 years ago, Winchester encouraged special orders. Their ’73 rifles came standard with round barrels but octagon ones were actually more popular. Standard barrel length was 24″ but versions as long as 36″ and as short as 12″ exist. Extra heavy and extra lightweight barrels were also available. A simple single trigger was normal but a single set or close-coupled double set arrangement were extra cost options at $1.50 and $3 each. Finish was usually blue but color case-hardened action, buttplate and forearm cap were available. Heck, even full nickel plating was an option.

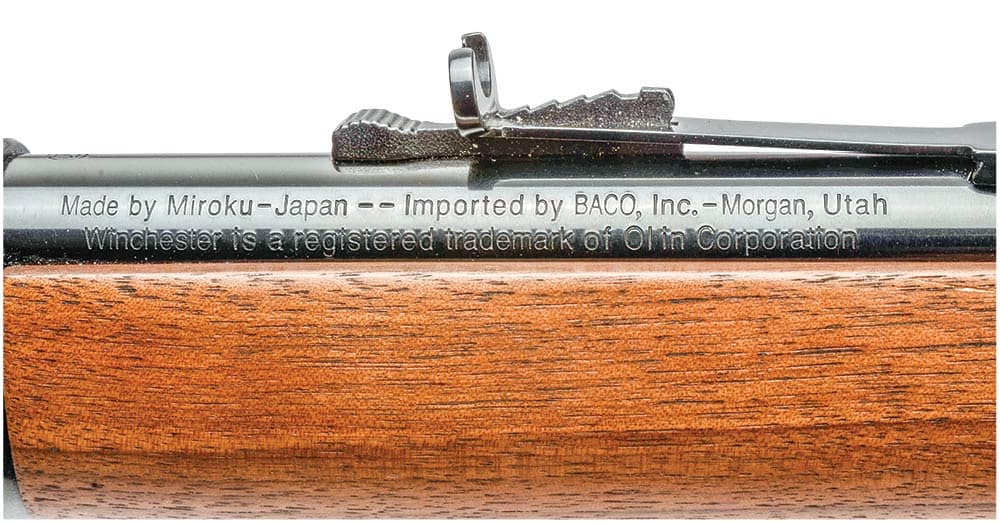

More original ’73’s were sold in rifle configuration while about one-third were made as SRC. The rarest of ’73’s were military style muskets and I’m lucky enough to have one of the approximately 12,000 made. I also have owned a rifle with a 28″ barrel, another with special-order extra-heavy barrel along with a couple with single-set triggers. Most of the options mentioned above can be had among the Uberti and Miroku ’73’s now being sold.

At this point let me clarify the difference between an SR and an SRC, even though both might have 20″ barrels. Winchester ’73 rifles were cataloged with rather deep, crescent steel buttplates while carbines had much less curved and wider steel buttplates. Rifles had steel forearm caps while SRCs had barrel bands. Rifles had notched slider-type rear sights while SRCs had flip up “ladder-style” rear sights.

The Browning/Winchester/Miroku ’73 .44-40 I have on hand now with a 20″ barrel is a Short Rifle. The Browning/Winchester/Miroku .38/.357 here — also with a 20″ barrel — is actually an SRC.

Earlier I stated the ’73’s basic design wasn’t especially strong but don’t think I’m saying they’re weak because the engineering was perfectly adequate for the cartridges and pressure limits intended. The bolt is closed with two toggles when the action is shut and I’ve been told by experienced gunsmiths who have checked out original Winchester ’73’s they will occasionally find one with a cracked toggle link. Not good!

So heed this: Reloading ammunition for ’73’s — from originals to modern-made ones — is not for the adventurous or stupid. A good example is detailed in Lyman’s reloading manuals under data for the .44-40. The standard Lyman Reloading Manual No. 50 — and/or their Cast Bullet Handbook No. 4 clearly indicates separate data for stronger rifles and what they consider weaker ones. Of course ’73’s are in the latter category and my final take on the matter is Winchester ’73’s made prior to the common use of smokeless powders should not be fired with smokeless powders. In their 1899 catalog, Winchester’s writers talk about the ’73’s uses but only mention black powder loads. However, in the same catalog when describing the wonders of Model 1892, they cover smokeless powder factory loads.

There are three points I’d like make about shooting black powder. (1) The Model 1873 is perhaps the easiest of all leverguns to clean up after shooting with black powder handloads. The sideplates come off with the removal of just a couple of screws, so the toggles and internals are easily reached for cleaning.

(2) If you choose a ’73 in .45 Colt, you’ll have much more to clean out of the exposed area once the sideplates are off. Modern .45 Colt brass is harder and does not obdurate to seal the chamber from gas leakage. This leakage is evident if you stand to the side while someone shoots black powder .45 Colts in a ’73 because there will be a puff of smoke arising from the chamber’s rear. Such leakage doesn’t happen with .32, .38 or .44 WCFs because their cartridge cases are of lighter construction and expand to seal the chamber.

(3) Smokeless power loads make a “pop” when fired. Black powder loads roar. They’re lots more fun!

This wraps up it up for me and the Model 1873. No matter what maker or vintage, when I take a levergun out of the vault for just plain fun, it’s always a ’73!