The Mauser C96

Shooting Grandpa's Bring-Back

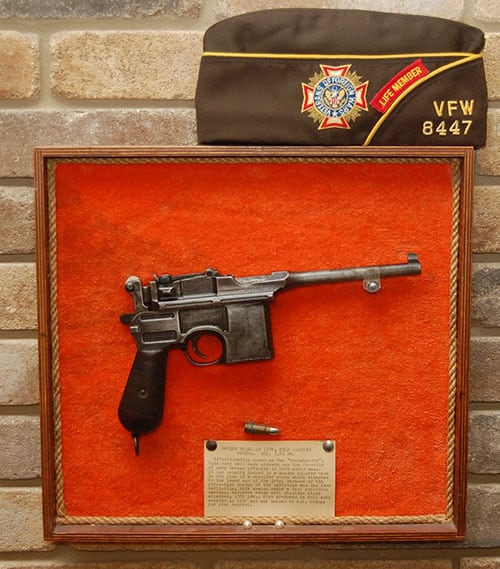

The old pistol mounted in the orange, felt-lined wooden box overhanging my grandfather’s basement bar always fascinated me. When I was barely big enough to acknowledge it, I first recognized it as Han Solo’s blaster in “Star Wars.” As I grew old enough to comprehend connections between lessons in history classes and my grandfather’s service in World War II, I realized it was a war trophy. And when I developed an interest in guns and shooting I learned it was a Mauser C96.

Melvin Bollig was not a historical figure, being one of many million enlisted men sent into war to do his bit and try to stay alive for a trip home. His stories of the war were sparse and tended to focus on typical enlisted man shenanigans: What he liked about range sessions, how much training he endured in the United States and England, and the time he and his platoon leader both “misplaced” their Garands after a notably drunken escapade somewhere in Europe.

There were a few stories about traveling by ship back home, which included being forced to discard various trophies by tossing them into the Atlantic. Being limited to one item to bring back, he opted to keep the Mauser pistol but had to discard its wooden stock. Specifics of duty after Normandy weren’t talked about, though Grandma said he suffered nightmares years after returning. As a child old enough to construct questions but not really ponder, I asked Grandpa how he got the pistol. His only explanation was, “There were times men had me in their sights and I had them in mine. I’m still here.”

After enlisting I had a better insight of my grandfather’s life as a soldier. I also better appreciated why he, like many troops who saw terrible things on the battlefield, didn’t like to talk about them. The true professionals are usually quiet about such matters. Other than his Veterans of Foreign Wars garrison cap, displayed proudly with his many antique John Deere replicas and the two, restored full-size B and G models he drove in parades and at antique tractor pulls, Grandpa didn’t display military memorabilia. His only other hint of combat experience was the pistol. A casual visitor might not ever know he had any military background at all, although he was a life member of VFW Post 8447 and American Legion Post 534.

Sage Advice

His advice upon learning my decision to enlist was to “go supply” (Quartermaster). Though he didn’t go into details, he wanted my high school-aged self to avoid seeing and doing the things he had to when he was my age on the European front. Of course, the nature of warfare has changed since then (just ask Jessica Lynch) but it was his best way of being protective given I went and signed a DD Form 4.

He left military life in the 1940’s, spent some time running a dairy farm (hence his love of old tractors) and then worked for decades handling big cats and other animals at the Henry Vilas Zoo in Madison. Having grown up on and then owning his own dairy farm before moving to the city, handling animals was a well-developed skill and sufficient to land him the job he would work for decades.

The Mauser C96 (Construktion 96) is a semi-loading, short recoil pistol originally manufactured by Mauser from 1896 to 1937 with copies made in Spain and China. The design originated with the brothers Fidel, Friedrich and Josef Feederle. Fidel was a Mauser employee, working as the superintendent of the experimental workshop for the company. He and his brothers began designing and prototyping the P-7.63 Feederle Pistol on their own as a side project. When the company decided to manufacture the pistol for commercial sale in 1896, Paul Mauser dubbed the C96 the “Mauser Military Pistol” to attract military buyers.

English cavalry officer and future British Prime Minister Winston Churchill was fond of the C96 and used one in 1898 at the Battle of Omdurman and again during the Second Boer War. Thomas Edward Lawrence (of Arabia) packed a C96 during the Sinai and Palestine Campaign and the Arab Revolt. Those who liked it generally did for its (for the time) high capacity and high velocity. The C96 has a distinctive look due to its long barrel, integral magazine in front of the trigger, rounded handle-like grip, and wooden holster/carrying case that also doubles as a shoulder stock. In English-speaking countries the gun was nicknamed “broom handle” for its unique grip. The Chinese dubbed it “box cannon” because of its square-shaped magazine and wooden, box-like stock.

The C96 was originally chambered in 7.63x25mm Mauser, a cartridge based on the toggle-locking C93 Borchardt’s 7.65×25mm round designed in 1893 chambered for the first mass-produced, self-automatic pistol. Mauser’s cartridge was essentially the same dimensionally but charged with 20 percent more propellant, hurling an 88-grain bullet at a muzzle velocity of around 1,400 fps. Given the C96’s long barrel and this higher velocity cartridge, the pistol had superior range and penetration than other pistols of the day and remained the fastest commercially available round until the .357 Magnum was released in 1935.

Improvements

A year into production, Mauser strengthened the action and added an extra locking lug to the bolt. The design was reworked again to motivate cavalry sales by way of a positive safety fully blocking the cocked hammer while allowing loading. Various hammer, safety and internal tweaks were done over the next decade but sales were stagnant until the Central Powers of the German, Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires had a sudden demand for arms in 1914.

The German Army had previously been more interested in 9mm Parabellum pistols, but wartime demand ramped up procurement and production of all arms. Mauser abided with German Army-ordered C96 pistols chambered in the cartridge and produced an initial run of 150,000 copies. These were dimensionally similar with the most prominent change in appearance being a large “9” engraved in the grip handles.

Following the Great War, with the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires dismantled, Germany was stuck with most of the blame and severe limitations on military production by the Treaty of Versailles. Mauser managed some sales, including continuing the C96 line. The so-called Bolo model was sold to Bolshevik Russia in 1921 and this variant comprised over a third of the C96’s made. To be compliant with the Versailles Treaty, Mauser produced the C96 with shorter 3.9″ barrels and smaller grips, which had the unintended consequence of making them easier to conceal. This variant’s popularity with the Bolsheviks is said to be the reason for the “Bolo” moniker.

In addition to the pre-war, fixed 10-round 7.63mm configuration, larger capacities of 20 and more rounds and machine pistol variants were offered based on patents by Josef Nickl. The “Pistol M30 Schnellfeuer System Nickl” M712 was a select-fire, full-automatic C96 with detachable magazines. Mauser then continued production of their long-running pistol line into the 1930’s but was losing market ground to other self-loading handguns and to copies from Spain and China.

While never officially adopted by any country as their primary sidearm, limited numbers were purchased by military and police forces in Germany, China, Indonesia, Italy, Norway, Persia, Turkey, as well as unofficial use by troops in a large number of other countries. By 1939 Mauser had produced over one million C96 pistols. Given copies made in Spain and China, total production is higher.

Historical and serial number research tells me my grandfather’s C96 was manufactured sometime during World War I. The serial number places it among a batch of about 150,000 Wartime Commercial pistols made for Germany between 1914-1918, with this particular one made toward the tail end of that lot. It very well could have been issued and in service before the armistice. By the time it was re-issued to the German soldier whose fate was met on the European Theater by Technician Fifth Grade Melvin Bollig, this pistol had already been in service at least a quarter century and was likely older than either man at the time.

Having “liberated” it from Germany and choosing not to cast it into the Atlantic, the pistol remained buried in a steamer trunk after getting stateside and was purposely forgotten for many years. After moving off the farm and into the city, Grandpa liked to keep busy with various hobby and restoration projects. He eventually built a display box to add his trophy to the ever-expanding collection of curios in his bar where it remained until his passing. Knowing I’d appreciate it most, Grandma bequeathed it to me.

Out Of Mothballs

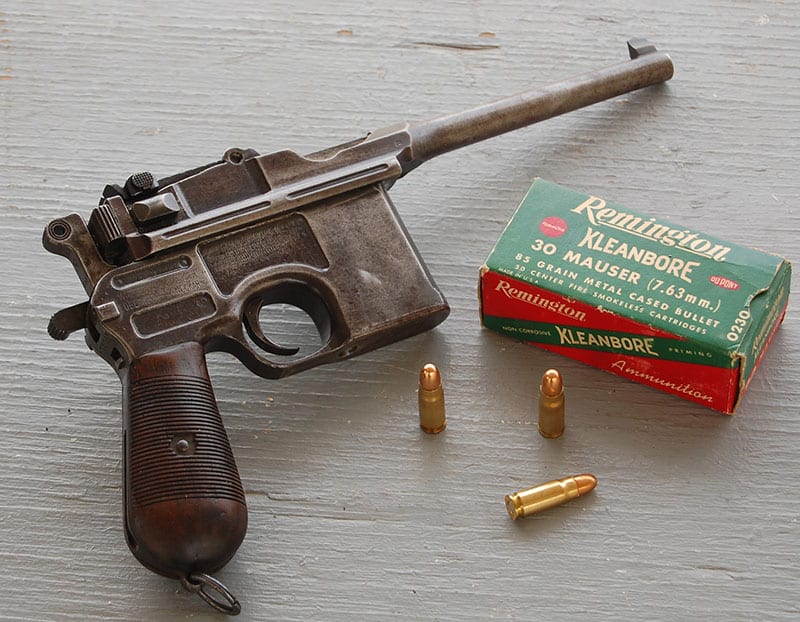

Seeing it displayed above my fireplace and coming upon a fair deal on .30 Mauser ammunition, my friend and mentor Bob Kolesar convinced me to resurrect the old warhorse. By the time I stripped the pistol to inspect and prepare it for our range session, this C96 was rapidly nearing 100 years since coming off Mauser’s Oberndorf factory floor with other World War I arms production. All things considered, the pistol is still in surprisingly good shape. Slipping cartridges into the magazine at the range was the first ammo the gun had seen since the Roosevelt administration.

All shooting was done standing, unsupported, and one handed — the way most would have shot back then. Recoil was sharp but not unpleasant. Despite the gun’s size, the near-magnum velocity gave a bit of flip but was quite controllable. The biggest obstacle to good shooting was the tiny sights. Like their rifles, Mauser’s sights are overly fine and consist of a leaf rear sight “V”-notch marked for elevation in hundred meter increments out to an optimistic 1,400 and paired with a Mauser trademark pyramid front sight. Even in bright mid-daylight conditions the sights were dainty. No one will confuse a C96 for a tuned ball gun and the bore on this specimen is in rough shape but holding under 8″ groups at 25 yards off our feet proved easy. Despite the less-than-pristine barrel, the gun fed and functioned without any problems.

The C96 is a study in 19th century engineering and craftsmanship. Every part is machined steel, the interlocking parts of the action are somewhat complex but completely functional and reliable, and the fit is first rate. Upon attempting initial disassembly and learning the first step was removing the magazine base plate from the cleared pistol, I was concerned this one was different as it appeared the magazine was one solid piece. Closer inspection revealed the base did remove; it was simply fitted so well no seam between the parts was evident. In a modern world of mass-produced polymer, stampings and CNC machines, the C96 is a triumph of the Industrial Revolution and a great historical artifact.

War Trophy Policy

During World War II the United States War Department had a much more open policy on troops returning with trophies. Back then, pertinent war trophy firearm documents were in two record groups: Record Group 407 (Army-Adjutant General Decimal File 386.3: Captured Property) and Record Group 165 (Records of the War Department General and Special Staffs, Office of the Chief of Staff Decimal File 332.2: War Trophies, Box 208 and 307.)

Records consist of discussions limiting war trophy firearms to one per soldier and provisions of Circular 155 published May 28, 1945 strictly forbid full automatic weapons. This policy was extended through the 1950’s. Records in Box 208 also limited War Trophy firearms to one per soldier. Normally, Customs would pass firearms not restricted by the National Firearms Act and would collect a duty for notably valuable firearms. If allowed, importing an NFA-regulated firearm required a formal application before Customs would clear it.

Generally, all military and merchant marines were held to Department of War policies then, though some individual services, such as the Army and Navy, had established separate procedures for war trophies. Soldiers were authorized to bring or send machine guns back to the United States until the practice was prohibited by Section VI of Circular 155, effective May 28, 1945. Preceding policy (Circular 353, Section III) authorized bringing or sending back almost anything. Concerns were subsequently expressed by authorities about NFA firearms.

The only valid form for enemy captured items from the European Theater was the AG USFET Form N 33 (Authorization to Bear and Retain Captured Enemy Equipment) and usually applied to pistols.

Our current Department of Defense has a different policy on war trophies than the War Department did during World War II. Army Gen. John Abizaid, the commander of US Central Command, put out the policy. Basically, under no circumstances can individuals take as a souvenir an object formerly in the possession of the enemy. It’s strictly forbidden to bring back any war trophies at all. US Central Command officials have been very clear service members can’t bring home weapons, ammunition or other prohibited items. A few soldiers trying to smuggle weapons back from Iraq and Afghanistan have gone through courts martial and others received Article 15 administrative punishments. Maj. Robert Resnick, an Army lawyer at Fort Stewart, Ga., noted, “There is a whole spectrum of punishments, depending on the severity of the offense.”