Bed Bites

Bolt Action Stock Fit: Don’t Let These Quirks Mess-Up Your Quest For Accuracy!

Amateur riflestock bedding turned into yet another American national pastime soon after World War II. The trend started because of two factors, one technological and one historical.

The technological factor was the development of epoxy just before the war. Originally developed for dental work, epoxies were soon applied to other uses, since they work well both as a strong glue and structural work. They’re basically a resin that, when combined with a semi-liquid “hardener,” cures into strongly cross-linked molecules. Other materials can be added to the mix for various applications, in the form of powders or small fibers. Hundreds of varieties of epoxy exist today, for uses from simple household gluing to weatherproofing metals to constructing spacecraft.

The historical factor also occurred soon after the war, when hundreds of thousands of “war surplus” rifles were sold at really cheap prices to US civilians. Some were kept as-is, but many were converted to hunting and target rifles by amateur and professional gunsmiths, many using epoxy to precisely mate the barreled actions to wooden stocks. To provide some structural support against recoil, bedding epoxies often included glass fibers, so the process became known as “glass bedding.”

Before epoxy, barreled actions were fitted into wooden stocks by painstakingly scraping away wood, a skill that took considerable time to master, but with epoxy even a so-called garage gunsmith could perform a practically perfect inletting job in a few hours. This upset many “real” craftsmen, who refused to use epoxy, but today even the dwindling number of custom stockmakers who still create functional art from walnut often “skim bed” their practically perfect hand-inletting with epoxy, both to reinforce the surface and to seal the wood from moisture and oil.

Quirk 1

However, one historical aspect of the epoxy revolution still commonly results in a stock-bedding quirk. A commonly held belief is not only the critical parts of the action need to be bedded (particularly the recoil-leg area), but an inch or two of the barrel. The most common justification is “support” of the barrel, even if most of its length is free-floated.

Even pretty skinny sporter barrels are perfectly capable of supporting themselves, as anybody who’s held one by the muzzle can plainly see, and exactly how a couple inches of epoxy at the rear of barrel “support” a barrel is rarely discussed. In reality, epoxy-bedding the rear of a barrel supports the action—or rather, some bolt actions.

Most of the common centerfire bolt-actions produced in the first half century after the introduction of smokeless powder had the front action screw in the recoil lug. The 1898 Mauser is the classic (and most abundant) example, but among the other bolt-actions with lug-screws were all the 1903 Springfield, 1917 Enfield, Japanese Arisaka, and Winchester Model 54.

This placed the screw at the front of the action, ahead of its “bedding surfaces.” As a result, tightening the screw tended to bend the receiver ring downward, resulting in uneven bearing of the two locking lugs used on all these actions, often resulting in poor accuracy. This was particularly true with military 98 Mausers, because the thumb-slot in the left receiver wall and slender tang made them pretty flexible.

Epoxy bedding the rear of the barrel prevented this bending, so was suggested by various authorities, including Roy Dunlap, author of Gunsmithing, first published in 1950, probably the all-time best-seller on the subject (it’s still reprinted now and then).

Since the vast majority of surplus bolt-actions had the front action screw in the recoil lug, epoxy bedding the rear of the barrel became part of gunsmithing lore, even though most gunsmiths didn’t know why, especially amateurs.

Big Switch

The technique’s still regarded as gospel, even among some professionals, but eventually most (but not all) new bolt actions placed their front action screw behind the recoil lug, basically right under the locking lugs. No accuracy problems occurred even with the screw torqued really hard, so the rear of the barrel didn’t need to be bedded to prevent the action from bending.

The first major bolt-action to make the switch was the pre-Model 70 Winchester in 1936, but soon after the war Remington brought out their Model 721 and 722, also with the front action screw behind the recoil lug. With minor and mostly cosmetic modifications the 721/722 became the Model 700.

Other bolt-actions with the front screw behind the lug include just about every model introduced since WWII with four exceptions. The Weatherby Mark V, Howa (also the action for the Weatherby Vanguard), Nosler Model 48 and CZ 550 all use the “old fashioned” screw in the middle of the recoil lug. However, these actions are very stiff, with heavy walls and thick tangs, so can’t bend much at all. This is exactly why my Nosler Model 48 Liberty in .26 Nosler shoots very accurately, even though its 26-inch, medium weight barrel is totally free-floated all the way to the receiver ring.

Erratic K98k

As a matter of fact, even 98 Mausers don’t absolutely require the “support” bedding of the rear of the barrel. I recently corresponded with a reader who acquired what he came to call “the Mauser from hell,” a sporterized K98 military rifle with the original barrel. He slowly worked through various issues, including buggered scope-mounting holes, but the rifle still kept scattering its shots, and not just over inches but sometimes feet.

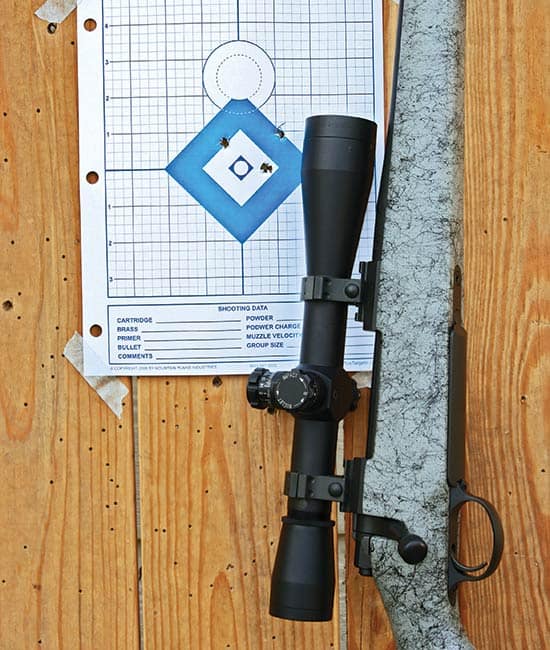

It turned out the barrel wasn’t free-floated, and he’d torqued the front action screw to 60 inch-pounds. I suggested placing a small shim, like the piece of plastic holding a bread bag closed, between the action and stock behind the recoil lug. This normally “lifts” the barrel enough to temporarily free-float it, so is a good test to see if floating will help accuracy—but I also suggested reducing the torque on the lug-screw to no more than 40 inch-pounds. The rifle’s first groups shrank to under 2 inches at 100 yards, and trying different bullets and handloads shrank them even more.

One of the problems here involves the recent abundance of torque wrenches among rifle loonies. This started primarily due to awareness of how over-tightening scope rings can result in stressing a riflescope’s internals, but many shooters suggest really torqueing action screws. This can help a “modern” bolt action with the front action screw behind the recoil lug, but had the opposite effect on his old military Mauser.

Mag Box Bind

Another common but also commonly undiagnosed problem is the magazine box binding against either the bottom of the action, or the magazine recess in the stock. The magazine box should have a little clearance both under the action and inside the recess. If it doesn’t, the symptoms often resemble a scope going bad—or even a 98 Mauser with the front action-screw over-tightened—and they aren’t necessarily cured by fixing the problem once.

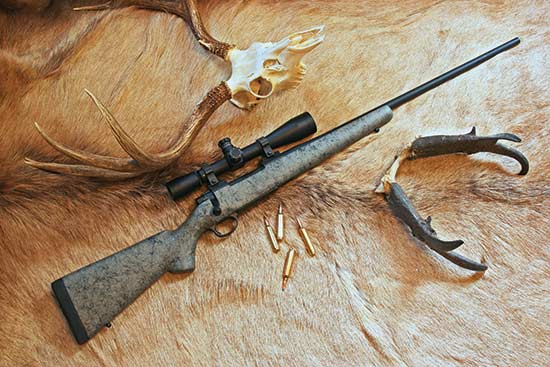

My modest collection of bolt-action centerfire rifles is just about evenly divided among rifles with traditional wooden stocks and those with synthetic, laminated and even metal stocks. I’ve had to readjust the bedding on a number of those stocks over the years, and one of the recent examples was a Remington 700 in .204 Ruger. Originally it had a cheap injection-molded plastic stock, eventually replaced by a lightly used walnut factory stock off a CDL 700.

With the recoil-lug area epoxy bedded and the barrel free-floated, the rifle shot even better than with the synthetic stock—for about a year, when it suddenly started throwing fliers. At first I thought the problem was fixed by tightening the action screws, since they’d loosened slightly as the stock shrank in Montana’s dry air. But the rifle still threw fliers, and the problem was eventually traced to the magazine box: The stock shrank just enough that retightening the action screws jammed the box against the bottom of the action. A half-hour with a file solved the problem.

Sour Synthetics

However, I’ve also seen the bedding go sour in laminated stocks and high-quality “lay-up” synthetics. The problem with laminates is they’re still wood, so despite their plywood construction can still warp, but the problem with lay-ups is they’re made of epoxy and synthetic cloth. Epoxy molecules can continue to cross-link (“cure”) long after the stock was made, often due to exposure to heat.

In fact, some of the best lay-up synthetics are heated after coming out of the mold, to increase the cross-linking, but even that may not truly finish the process. In 2016 I had to re-bed a high-grade lay-up because the free-floated barrel no longer floated, instead making contact with the bottom of the barrel channel in the fore-end.

Even the modest amount of epoxy used in action bedding can also squirm somewhat after a year or three of use and curing. Some brands are more stable than others, but I’ve yet to find one that’s absolutely stable after curing.

While most newer bolt-actions have free-floated barrels, many are floated in theory only, especially injection-molded stocks made of relatively flexible plastic. I’ve lost count of the injection-mold stocks requiring some additional floating, mostly at the tip, accomplished in a couple of minutes with a round rasp. A round rasp is also quite handy for removing the “tip hump,” still used on some factory rifle stocks to put upward pressure on the barrel, both in synthetic and wood stocks. The rule-of-thumb is to create enough clearance so you can’t press the fore-end-tip against the barrel when squeezing both firmly in your hand—so no, sliding a folded piece of paper between fore-end and barrel doesn’t always demonstrate the barrel is adequately free-floated.

Bed The Barrel?

A few modern rifles, however, are fully bedded, with “neutral pressure” all the way along the barrel—also obviously qualifying as “support.” This can improve accuracy, a good example being the superb New Ultra Light Arms rifles. Full-fore-end bedding can especially help slim barrels by dampening vibrations, and I’ve done the job myself with epoxy on both synthetic and wood stocks, though there are two caveats.

First, the stock material must be reasonably stiff. A flexible fore-end, like those on many injection-molded stocks, results in inconsistent vibration of the barrel—the exact problem free-floating or full-fore-end bedding is supposed to cure. Second, the bedding must extend all the way to the fore-end’s tip. If there’s even slight looseness in the bedding just behind the fore-end tip, accuracy probably won’t be all it can be. This slight looseness sometimes occurs when a barreled action is placed into inletting filled with a layer of freshly mixed epoxy, due to a slight twisting or rocking of the barrel.

Back when epoxy bedding was new, many people claimed a layer of “glass bedding” in the fore-end prevented wood from warping. I’ve found a thin layer of cured epoxy isn’t nearly as strong as wood’s ability to warp, one reason several fore-ends on my wood-stocked rifles have been rebedded over the years. This is also why I avoid bedding the rear of a rifle’s barrel if it isn’t necessary, having even seen an inch or two of barrel-shank bedding go sour. Not applying epoxy there simply avoids the possibility of having to redo the job later.

Epoxy is a great material for stock bedding and even stockmaking, relieving action stresses and even stabilizing barrels. But it doesn’t cure all the possible problems, unless we understand the principles of stock bedding before starting the job.