Forgotten Or Unknown

Somebody’s Gotta Speak Up For Them …

A string of coincidences brought these forgotten fragments to light. Naturally I thought of inflicting them on—excuse me, sharing them—with you. You’re welcome!

In the chaos of getting settled in our new compound, one of the youngsters stopped at a gas station and purchased several foam cups of a thin, nasty dark liquid falsely advertised as “coffee.” He handed one to Van Zyl, who was perched on a packing crate, and said “Here’s a cuppa Joe for ya.” VZ slurped up a mouthful and a second later leaped to his feet, turning purple and spewing the noxious stuff in the dirt.

“Hoo iss diss Joe? he demanded. “He shuud be beat-en! Hiss coffee iss KRRAAAPP!” If you could hear him say it, you’d know why I spelt it that way. VZ was unfamiliar with “Joe.” I explained, partly to allow time for Robbie to scamper away before he could be throttled by an angry giant.

“Joe” would be Josephus Daniels, who was appointed Secretary of the Navy by the notorious prig, Woodrow Wilson. Presumably, they both hated Marines and shared the morbid dread that somewhere, a sailor may be happy. Daniels campaigned against “bawdy houses” around naval bases, increased the number of chaplains and, most damningly, banned all alcoholic beverages. He pushed coffee. Sailors and Marines were sentenced to swill nothing but military coffee—an oxymoron except in certain chief’s messes aboard destroyers and submarines. Daniels became the most reviled man in modern military history.

Coffee was bitterly referred to as “having a cup of Josephus Daniels,” then “a cup of Joseph,” and finally, “a cuppa Joe.” At some point the monster was forgotten, but the term lived on.

Huh? What’s Your Name?

From a photo found in an old file: In June 1944, American paratroops in Normandy captured an Asian-looking Wehrmacht soldier whose command of German seemed limited to yes, no, and food, please. They presumed he was Japanese and put him in a POW camp. The Yanks were kinda short of Japanese-speakers in France. Slowly, the incredible story of Yang Kyoungjong came out.

A native Korean, in 1938 he was conscripted by Imperial Japan as an 18-year old laborer and shipped to Manchuria. For Koreans under Japanese masters, conditions were hellish. When Soviet resistance stiffened, Yang and his friends were drafted into the Imperial Army and chiefly used in suicide attacks. Yang was captured at the Battle of Khalkhin Gol and shipped to a slave-labor Soviet lumber camp in Siberia, a pocket of frozen hell. Only the strongest and luckiest survived.

When Germany pushed deep into Russia, Yang and other POW’s were offered the choice between serving in the Soviet Army or being shot dead on the spot. The Sovs also used their “slave troops” as cannon fodder, “urging” them into battle at machinegun-point. Yang was captured by the Germans in the Third Battle of Kharkov—and then conscripted into the German Army! He was serving in a labor/cannon fodder “Eastern Battalion” when the Allies landed. The poor guy probably thought he would be conscripted by the Yanks too.

Ultimately, Yang immigrated to the US, where he lived quietly in Illinois, and died there in 1992. I have often hoped he took delight in shopping for fresh meat and produce, sleeping in a warm, clean bed, and got to kick back in the evening and watch a little TV.

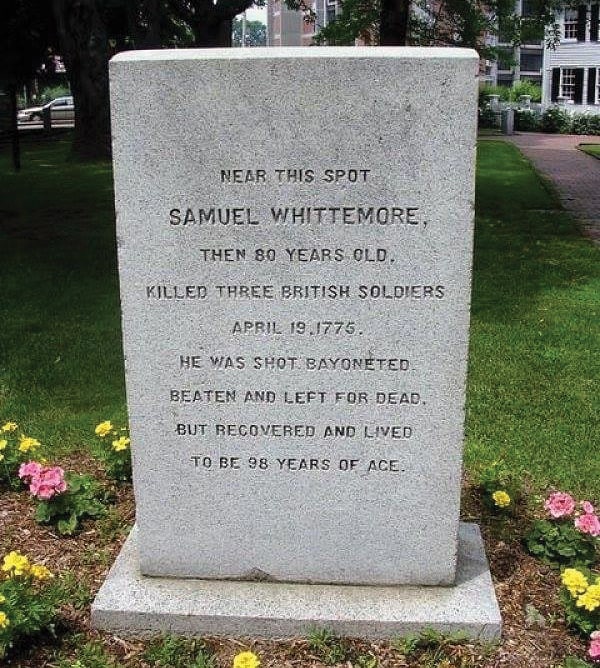

Toughest Nut In Massachusetts?

One of our new guys mixed up Robert Rogers of Rogers’ Rangers with the story of an almost-forgotten guy who had to be one of the toughest men to fight in the American Revolution: Samuel Whittemore. We straightened him out.

Sam was born in England in 1695, and came to North America as a captain of Royal Dragoons in 1745. He fought the French in the capture of Fort Louisburg, coming away with a French officer’s sword. He left service after the war and settled in Menotomy, Mass., where he married twice, fathering three sons and five daughters.

When war with France flared again in 1758, Sam was 64. When he heard Fort Louisburg had to be taken—again—he joined a Colonial Regiment, which “reduced the fort to rubble.” He then hooked up with General James Wolf for the march and assault on Quebec. When there was no more fighting left to do he went home.

Ah, but then the Indian Wars called in 1763! Sam, nearly 70 now, kissed his family goodbye and rode to battle against Chief Pontiac in the wilderness. He returned from that campaign with a pair of dueling pistols.

Over the next decade, he came to believe a break from the Crown was necessary, telling his neighbors he wanted his descendants to, “…enact their own laws and not be subject to a distant king.”

Samuel was 80 years old on April 19th, 1775, when the retreating redcoats were fleeing back to Boston from Lexington and Concord, bayonetting wounded colonial militiamen and torching homes in their path—right through Menotomy. Sam grabbed his musket, sword and dueling pistols, and walked out to the road, where he sat down and waited. His militia buddies urged him to take a better, more distant position. He ignored them.

His pals fired on the lead grenadiers of the 47th Regiment of Foot and fell back to reload. Sam waited. When they were at point-blank range he stood and fired his musket, killing one grenadier. He drew his pistols and fired, killing a second grenadier and mortally wounding another. As several redcoats closed with their bayonets, he drew his sword and commenced swinging. He was shot in the face, the slug tearing away his cheek and knocking him down. He continued hacking as they bayonetted him 13 times, beat him with their rifle butts, and left him for dead in a pool of blood.

A couple of his neighbors witnessed the entire melee. They stole down later to recover his body. They found Sam trying to reload his musket. Doctor Nathaniel Tufts declared it would be futile to even dress his wounds, and sent him home on a door to die surrounded by family.

Sam wasn’t ready to die. He lived an active life for another 18 years, dying at 98.

Finally, A Requiem

Found in an old jacket pocket, a postcard from Bruno the Belgian, just before he retired from the Legion. It shows the Place des Etats-Unis in Paris. Atop the monument to the American volunteers there stands a statue of a young Legionnaire. His face was taken from a photo of an American poet-warrior who wrote one of the most moving poems ever penned on war: “I Have a Rendezvous with Death.” His name was Alan Seeger. We haven’t space for the poem here, but you can find it at the link above. Please do.

Born in New York in 1888 to a literary and musical family, he attended Harvard, where he wrote and edited for the Harvard Monthly and became known as a serious and accomplished writer and poet. In 1914 he moved to the center of European poetry—Paris—for an extended visit. It wasn’t extended. He arrived just before a bumbling anarchist shot a 3rd-string archduke and kicked off World War I.

America would not enter the war for 3 years, and as a non-citizen, Alan couldn’t join the French Army. He enlisted in the Foreign Legion. Found to be as brave as he was articulate, he was by all accounts a good soldier and a hard fighter. Soon after writing the poem he kept that rendezvous. Bleeding to death from several machine gun wounds, he cheered his fellow Legionnaires on in a charge which broke the German lines at Belloy-en-Senterre on July 4, 1916, during the greater Battle of the Somme.

The Legion has not forgotten him. Maybe we shouldn’t either, huh?

Connor OUT