Point Shooting: The Untold Story

Little Known Facts About The Evolution

Of Applegate-Style Point Shooting

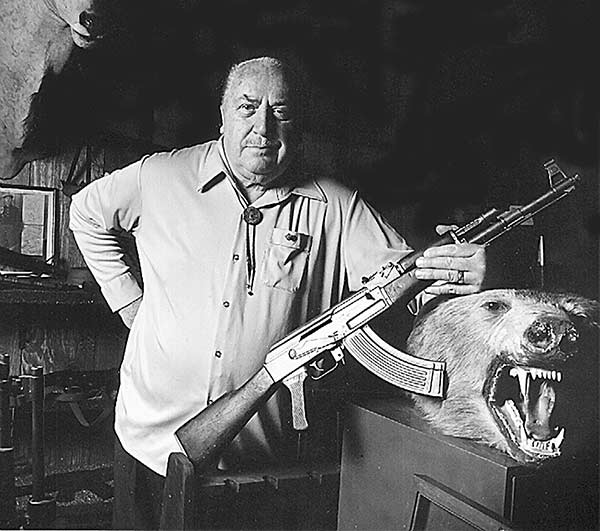

Colonel Rex Applegate is a name that should be familiar to all students of combat shooting. One of the true legends of the close- combat sciences, his contributions to the field spanned more than half a century and included practically every one of its disciplines. From unarmed tactics to knife fighting to riot control, the Colonel did it all and did it exceedingly well.

But the Colonel’s greatest passion — and arguably his most significant contribution — was his research and promotion of handgun point shooting.

I know at this point all the sighted-fire pundits out there are conditioned to grunt, roll their eyes, and dismiss point shooting as nothing more than spray-and-pray, un-aimed hip shooting. Well calm down, take your medication, and keep reading.

The purpose of this article is not to rehash the traditional point shooting versus sighted fire controversy. In my opinion, all forward-thinking combat shooters already understand the need for — and the respective limitations of — both point shooting and sighted fire and include both in their personal skill sets.

So instead of beating (or even shooting) a dead horse, we will shed light on some of the lesser known aspects of point shooting and the challenges faced by Colonel Applegate in his efforts to prepare men to go off to war. We will also look at how the Colonel’s point shooting program changed over time and some of the unexpected results of those changes.

The information in this article comes from in-depth analysis of the Colonel’s works, but more importantly from firsthand range instruction, professional collaborations, and countless conversations during the last few years of the Colonel’s life. For the record, my first introduction to Colonel Applegate’s work was when I read his book Kill or Get Killed when I was about 13 years old. About 20 years later, I was hired by Paladin Press (still publishers of the book and the Colonel’s other works) with the specific purpose of establishing their video production department to produce point shooting videos with Colonel Applegate. In fact, my acceptance for the position was actually contingent upon the Colonel’s approval; if he didn’t like me, I didn’t get the job.

Fortunately for me, the Colonel not only took a liking to me, he also appreciated my active interest in the history and tactics of close combat. To ensure I could accurately express his methods in the videos we produced, he personally mentored me in point shooting and other topics. Ultimately he was pleased enough with my understanding and skill he invited me to co-author a book on the topic with him, titled Bullseyes Don’t Shoot Back. Needless to say, this was an incredible honor and will always remain one of the highlights of my career.

During our collaboration on the book, the Colonel shared a lot of information with me about the history and development of point shooting. However, to present the strongest case for the modern application of the system, he asked we not include those details so the book could focus on the application of the technique in today’s world. For the scope of that project it was appropriate, but the time has come to tell the full story.

Origins Of The Technique

When Colonel Applegate was personally recruited by the legendary “Wild Bill” Donovan (director of what began as the Coordinator of

Information (COI) and later became the Office of Strategic Services OSS), he was initially paired with another close-combat icon, William Ewart Fairbairn. With decades of experience with the Shanghai Municipal Police, Fairbairn already had a highly evolved curriculum of armed and unarmed combat to offer. The system — including the point shooting system he developed with his Shanghai colleague Eric Anthony Sykes — therefore became a significant turnkey part of the OSS curriculum. However, it wasn’t the only influence on Colonel Applegate’s approach.

Those familiar with the Colonel’s history know he also conducted extensive personal research into combat shooting — including

research into the methods of Western gunfighters. In the course of this study, he discovered a letter written by the legendary Wild Bill Hickok in which Hickok explained the secret of his gunfighting success. Specifically, he revealed during his gunfights he always took the time to raise the gun to eye level before firing. That revelation really resonated with Colonel Applegate and became a key element of his preferred shooting method.

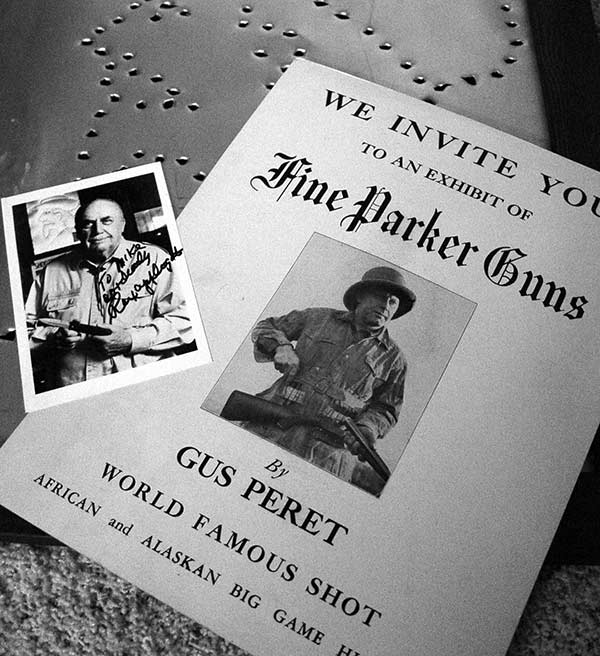

A somewhat lesser-known fact is one of the Colonel’s earliest shooting influences was his uncle, exhibition shooter Gus Peret. Like most exhibition shooters of the early 20th century, Peret had uncanny eye-hand coordination and performed feats including both incredible kinesthetic/point shooting and the amazingly precise use of the gun’s sights. Through Peret the Colonel learned at a very early age both the advantages and limitations of both approaches to shooting. He also learned there is a huge difference between the skills of a naturally gifted shooter with an unlimited supply of practice ammo and the capabilities of the common man. That understanding would later serve him and his students very well.

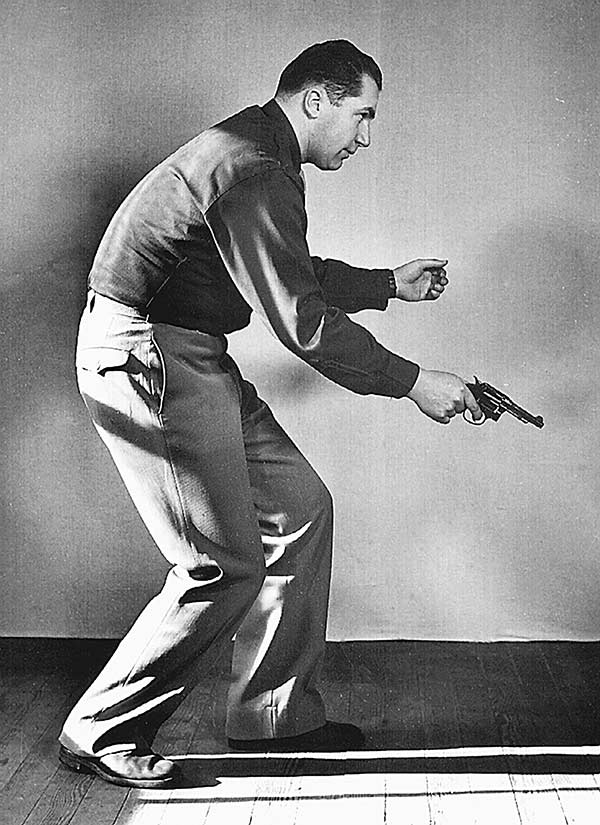

When you combine these influences and compare the WWII era Applegate technique with Fairbairn’s technique, there is one major difference. While Fairbairn acknowledged that shooting from eye level was preferable, he placed a heavy emphasis on what he called

the “Three-Quarter Hip” position, in which the gun hand was only raised to center-chest level. The Applegate technique, however, reflected his own research and experience and adamantly advocated raising the gun to eye level. In fact in his classic Kill

or Get Killed he specifically warns against hip shooting and other belowline- of-sight methods and clearly separates the from his recommended method of combat point shooting.

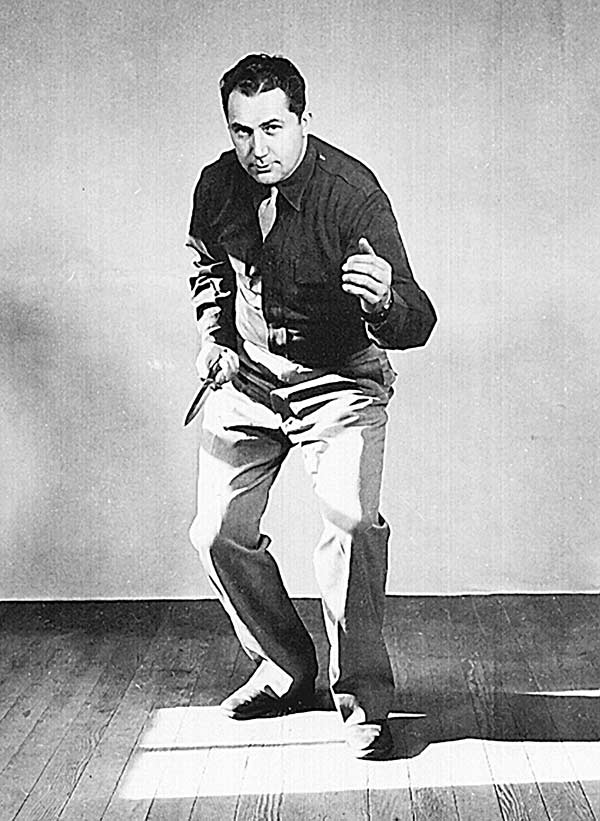

Thou Shalt Not Shove

One of the other key elements of Applegate-style point shooting is the concept of locking the wrist and elbow and raising the gun to the line of sight. The reason for this is to prevent shoving the gun forward at the target — an action when fueled by the gross motor skills of fear-induced stress causes a violent downward whip of the muzzle at full extension. Even at short ranges, this can cause rounds to impact much lower than the intended point of aim and, under extreme stress, even into the dirt in front of the target.

In all of his teaching, Colonel Applegate explained the effects of shoving the handgun are most pronounced when the shooter begins from a muzzle-up-and-downrange ready position — unfortunately the official “safe” position for most military firearms training. However, the Colonel also confided “raising the arm like a pump handle” also helped correct another marksmanship problem of the WWII era: the influence of films, particularly Westerns.

Since the action in Western movies focused on the use of single-action revolvers, the most familiar shooting technique to the average man at that time was to raise the muzzle, thumb cock the hammer, lower the gun, and fire. Since many of the recruits Colonel Applegate had to train were selected for skills such as such as foreign language fluency, area knowledge, etc., they were by no means seasoned shooters. When given a handgun, they shot based on what they thought they knew from the movies. Just as a kid today might

reflexively roll the gun over “gangsta” style or adopt a muzzle-up, cup-and-saucer “Full Sabrina” ready stance, novice shooters in WWII often tended to shoot like their heroes in the movies. The “pump handle” raise helped cure that.

Grip And Centerline:

In Fairbairn and Sykes’ book Shooting to Live, considerable attention is paid to the importance of understanding the vertical centerline of the body and making sure that the wrist of gun hand is bent slightly outward (to the right for a righthanded shooter) to align the bore with that centerline. By doing this, and following the natural instinct to turn your entire body to square up with a lethal threat, you automatically point your centerline and the gun at the target and achieve proper windage.

While Colonel Applegate’s early teachings also recommend bending the wrist slightly, he placed a much heavier emphasis on the importance of bisecting the angle of the web of the thumb when assuming a grip on the gun. In fact, in Kill or Get Killed, he recommends the centerline position is only mandatory during the early stages of training. As the shooter becomes more proficient, he can relax his technique and allow the gun to move away from centerline — as long as he’s still getting acceptable hits.

During the production of the video Shooting for Keeps and the writing of Bullseyes Don’t Shoot Back, I asked the Colonel about the importance of the centerline concept. Once again, he did not consider it a major factor and not nearly as important as bisecting

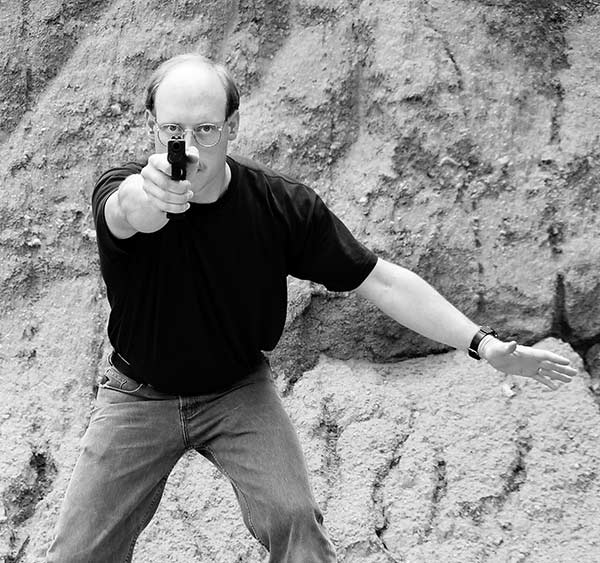

the angle of the web of the thumb to get the weapon bore on line with the forearm. Consistent with his wishes, I didn’t emphasize it. However, I noticed a significant difference in the performance of the shooters who appeared in the video — one of whom used the centerline concept and the other, who didn’t.

In one scene, the Colonel wanted to show how ordinary paper plates not only made excellent center-mass targets for shooting practice, but how they could be easily hit with proper point shooting technique. We set up a series of plates spaced laterally and the centerline shooter — his grandson — had no problem quickly working his way down the line scoring a hit on each plate. The non-centerline shooter, who was also a law enforcement officer personally trained by the Colonel, had developed a habit of maintaining a straight wrist. Although he compensated for this like most shooters — by pulling his right shoulder back slightly — his ability to transition laterally between targets was never as good as the centerline shooter.

Years later, after the Colonel’s point shooting curriculum had been officially adopted by Ohio’s Hocking College and become the law enforcement training standard for many law enforcement agencies in that state, I ran into a Brazilian friend of mine who had gone through the program. He knew I had trained with Colonel Applegate and coauthored a point shooting book and immediately said, he “had to ask me some questions about point shooting.” My equally immediate response was, “Are you wondering why you shoot to the left at longer ranges?” I interpreted his stunned expression as a “yes” and proceeded to explain the subtleties of bending the gun-hand wrist to put the bore on centerline and the effects of failing to do so. Based on my research following the Colonel’s death, I found shooters with same-side gun hands and master eyes can often “cheat” the centerline concept by bringing the gun up in front of the master eye and pulling their shoulder back slightly. However, it seems they still don’t shoot as well when using this method to shift between laterally spaced targets.

Combat Mindset

One of the biggest misconceptions about point shooting is its advocates claim it will produce the same level of accuracy as sighted fire. Colonel Applegate never claimed this and made it clear point shooting is intended to achieve acceptable accuracy and center-mass hits in the conditions of actual combat. Curiously, he still made use of the common belief tight groups on a two dimensional target equates to (or at least creates the impression of) combat proficiency.

Many of the students the Colonel trained had very limited time to develop combat skills. In some cases, they only had a few hours of firearms training before they were shipped overseas. To give them the basic skills they needed and to instill confidence, they were taught point shooting at very close ranges — usually only 2-3 yards. At this distance, even novice shooters had no problem achieving good center mass groups. They also unknowingly got accustomed to operating at very close range and experiencing things like muzzle-blast overpressure. This positive experience was very empowering and did much to instill students with a proper combat mindset — an asset that is much more important in a real fight than sterile, square-range shooting skills. This type of approach was common in WWII training methods and was instrumental in developing both basic, reliable, combat skills and the fighting spirit to apply them effectively.

Colonel Applegate’s version of point shooting was the perfect solution for a critical training challenge in WWII. In later years, it also served as a tremendous catalyst for change in our approach to modern combat shooting methods. There is no doubt it has saved lives and helped empower countless servicemen to do their jobs more effectively in combat. The proof is in our freedom.

THE MOST SPECIAL Of THE FITZ SPECIALS:

COL. REX APPLEGATE’S NEW SERVICE “FITZ SPECIAL”

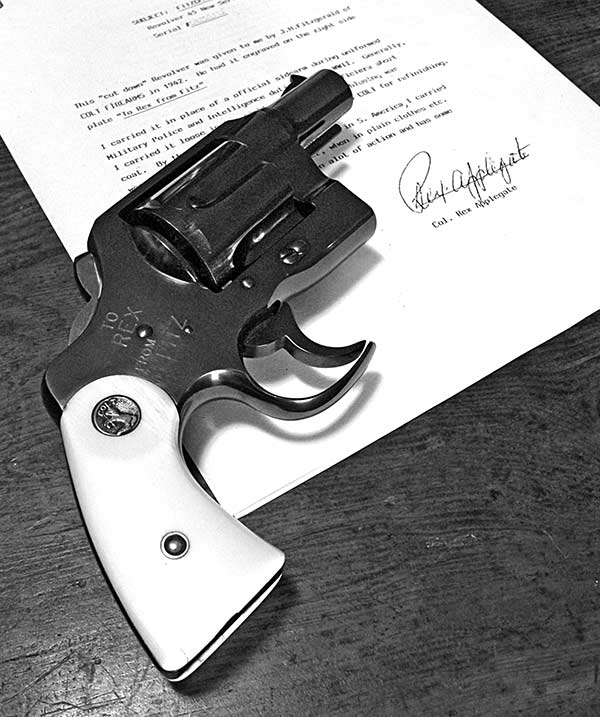

One of the most interesting and controversial styles of carry gun ever developed was the “Fitz Special.” The brainchild of renowned exhibition shooter and pioneer of modern ballistics J.H. Fitzgerald, the Fitz Special was, quite literally, the precursor of the modern snubnose revolver.

Developed while Fitzgerald was an employee of Colt firearms, the design began with a fullsized revolver. Both the barrel and the butt were cut down to reduce the overall size of the piece and make it more concealable. All sharp edges were “dehorned” and the hammer was bobbed to prevent snagging — an important consideration since these guns were often carried in pockets or pocket holsters. The most distinctive — and controversial modification, was the removal of the front portion of the trigger guard. This was done to allow the trigger finger to more quickly and easily find the trigger under stress. These unique guns were all personally smithed by Fitzgerald and were never part of Colt’s formal production. In fact, it appears Colt maintained no official records regarding these rare weapons and they were all given away to very select recipients of Fitzgerald’s choosing.

Although original Fitz Specials are a rare breed, perhaps the rarest and most famous of them all was the .45 New Service revolver Fitzgerald made for close-combat legend Colonel Rex Applegate. Boasting all the modifications that characterize a true Fitz, this one also included solid ivory grips and an engraving on the right side plate that reads “To Rex from Fitz.”

Fitzgerald gave this one-of-a-kind revolver to Colonel Applegate in 1942 and the Colonel carried it as his official sidearm throughout WWII. According to the letter of provenance in the Colonel’s unpublished book on his gun collection, “This formidable handgun has seen a lot of action and has some “notches” in its pedigree.” By the end of the war, most of the bluing had worn off and the Colonel sent it back to Colt for a careful refinishing before retiring it from active service. This gun remained a centerpiece of the Colonel’s collection until his passing in 1998. At that time, it was purchased by the Colonel’s close friend and founder of Paladin Press, Peder Lund. Several years later, in a tremendous act of generosity, Peder honored me by presenting it to me in recognition of my efforts to continue Colonel Applegate’s point shooting legacy. Along with several other unique knives and firearms personally carried and shot by the Colonel, it is the most cherished piece in my collection. It is also an enduring reminder of my friendship with Colonel Applegate and Peder Lund.

Sign up for the Personal Defense newsletter here: