SHOOT MORE FOR LESS

Getting Started In Handloading

So you’ve grown weary of paying for factory ammo and decided to start handloading. That’s all well and good, but I’ve known at least 1,000 handloaders in my lifetime and exactly one spent less money.

When in high school in the 1950’s the late Eddie Simons mail-ordered a “sporterized” military Mauser chambered in .30-06. He thought scopes were unreliable (back then many were) so shot the rugged military sights. He also bought a basic loading press, powder scale, set of dies and a Speer manual, and was still using the same rifle and tools when I met him in the 1970’s, and did so until he went to the Happy Hunting Grounds. He always loaded whatever primers and 180-grain bullets were cheapest at the local sporting goods store with the middle charge of IMR 4320 in the Speer book. His freezer was always full of deer and elk meat, so both his rifle and handloading tools had paid for themselves long, long ago.

Most handloaders, however, blow their per-round savings on shooting far more, plus buying more tools, often for different cartridges. They’re usually what a friend calls “churners,” always buying, selling and trading in a constant search for the firearm that will change their life. They handload to make more precise ammo, or to make more ammo quicker, or both, and often “experiment” with different bullets, powders and primers.

If you’re unsure about whether you’ll be one of the 99.9 percent or an Eddie Simons, you can begin with even less than Eddie—though the first item you should purchase is an old-fashioned, printed-on-paper loading manual. Yes, there’s a pile of loading data on the Internet these days, along with plenty of free advice on tweaking handloads to shoot more accurately, or bullets for bull elk or long-range targets, but not so much on the basics of turning an empty case into a loaded round. The latest Lyman, Hornady, Nosler and Speer manuals contain the basic information, and even if you have a handloading mentor for hands-on demonstrations, a manual will provide some additional info, along with a reference for when your mentor isn’t around.

After buying a manual and actually reading the how-to-handload section, you can start considering tools. If your handguns or rifles are in common chamberings, you can start the way I did in 1966, with a Lee Loader, the simplest reloading kit in the world. Unlike presses, Lee Loaders don’t need to be bolted to a bench, or even the shelf across the back of Eddie Simons’ living room closet. Instead they only require a reasonably hard surface such as a piece of scrap plywood and a mallet.

My first Lee Loader was for the 7.62x54R Russian, because in the mid-1960’s thousands of Mosin-Nagants flooded the US—just like they do today, demonstrating once again that history repeats itself. The Lee Loader cost me $6.95, and today the price is $39.98, often on sale at a price that beats inflation by about 20 bucks.

I also bought some Norma brass, a pound of IMR 3031, 100 Winchester primers and 100 Sierra bullets, and started handloading, learning many interesting and sometimes contradictory things. First, despite their low price, Lee Loaders make great ammo. In fact, they’re similar to the hand tools used by benchrest shooters. Five years ago I became curious and bought a new Lee Loader for the .22 Hornet, using it to make some of the most accurate ammunition ever fired in my very accurate Ruger No. 1B, with 5-shot groups averaging under 1/2-inch at 100 yards. Hornet handloads put together on my $300 press with $100 target-type dies don’t shoot any better.

However, a Lee Loader only neck-sizes brass. This works with moderate loads if they’re shot in the same rifle or handgun (especially a bolt action or revolver), but eventually most neck-sized brass needs full-length resizing. Plus, brass also occasionally requires trimming, since it stretches during firing, and the Lee doesn’t trim. A Lee Loader’s also slow and noisy, and the powder scoop only works for certain limited charges—if you have one of the powders on its short list of loads.

Growing

So I started acquiring other tools, first a scale to experiment with powder charges. Within five years I had a press and several sets of dies, because naturally I had more rifles. But I still have several Lee Loaders for various rounds, including the .30-06 and .357 Magnum, as a backup in case what passes for civilization collapses or, worse yet, my more sophisticated loading tools break down. They include many expensive tools made by companies known for high quality, but they also include others made by Lee Precision. I’ll gladly pay the price for really good tools, but am also not against saving money, and Lee makes some very good stuff for very attractive prices.

Both Lee and Lyman offer hand presses that don’t require mounting on a bench, though both are more limited in use than bench-mounted presses. They’re perhaps handiest for loading at the range, saving a lot of time if the closest range requires a considerable commute.

With a bench setup, the primary tool needed is a simple single-stage press, with one hole for dies. You’ll also need a powder scale, powder funnel and case trimmer, plus dies and shell holders for your cartridges. Handy but not necessary are a loading block with holes to hold cases, case lube and a chamfering tool. But you can make these or get by with other solutions, such as a pocketknife and a file for chamfering. Lubes aren’t required if you use carbide sizing dies for straight-sided handgun rounds.

Most bench-mounted presses come with a priming mechanism, but many handloaders prefer a separate tool, whether handheld or bench-mounted. This also includes handloaders who use Lee Loaders, because the repriming process is hammering the case down over a primer, and if you get careless the primer can go bang. However, many handloaders prefer separate priming tools because they can provide a finer feel for primer seating. I also like to have at least two priming tools, because they tend to break more than any other handloading gadgets, and if you can’t reprime cases it doesn’t do much good to load the powder and bullets.

Many loading-tool companies offer collections of essential tools, priced lower than if each tool was purchased separately. Lee offers one with a press, powder scale, hand priming tool, mechanical powder measure, case trimmer, case lube and a chamfering tool for $186 and it is often discounted. Other companies sell similar collections, though usually a slightly different mix. One of RCBS’s doesn’t include a case trimmer, but does have the latest Nosler manual and a loading block. Redding sells several variations, including one without a press and dies, and some including a set of dies.

Most companies also sell kits with more sophisticated presses, whether turret presses with revolving tops with several holes, which cuts down on die-changing time, or progressive presses, where each pull of the handle results in a loaded cartridge. But I’d advise starting with a single-stage press, both to save money and to get a feel for what your needs might be. If you eventually decide on a more complex press, a basic single-stage press is still a very useful accessory.

Some other tools can refine the process. The first on my list would be a caliper for measuring case and overall cartridge lengths. Luckily, stainless-steel dial calipers can be purchased for around $25 these days. You’ll probably also eventually want a micrometer, and there I’d suggest a digital model. It’ll be pricier than the caliper, but worth it.

The next major tool should be a chronograph. They not only measure the actual speed of your handloads, but provide an additional check of consistency and even pressure. Traditional indications of excessive pressure such as sticky extraction often don’t occur until pressures are already too high, but if your handloads show a lot more zip than listed in pressure-tested loading data, then your handloads are producing more pressure.

Speed Kills

Now, some handgun and rifle shooters think obtaining more velocity than wimpy factory loads is the main advantage of handloading. Some even believe getting another 100+ fps proves they’re highly skilled handloaders. Often they survive, but the best way to get extra velocity out of a .38 Special or .30-06 is to trade it for a .357 or .300 Magnum. Not only will your handloads be safer, but brass lasts a lot longer, saving money you can spend on more powder and tools.

Until recently all chronographs used light screens, and had to be set up at least 10 feet in front of the muzzle. Today several use other sensors and can be mounted either on the muzzle or sit on the bench, handy on public ranges because you don’t have spend time in front of the firing line setting them up. However, inexpensive light-screen models are still the most affordable, and the model I recommend is the ProChrono Pal. I got mine from Brownells for around $100, and unlike some other inexpensive chronographs I’ve used, the ProChrono rarely misses shots and is pretty consistent in different light conditions.

To really save money when loading handgun and rifle ammo it’s necessary to make your own bullets, usually by casting, though more expensive tools can make jacketed bullets as well. Luckily, Lee makes excellent, inexpensive bullet molds (as well as other casting tools), and I’ve used Lee molds to produce rifle bullets capable of grouping under an inch at 100 yards. The array of Lee molds isn’t vast, however, the reason I also own molds from Lyman, RCBS, SAECO and some specialty makers.

Even molds higher-priced than Lees quickly pay for themselves, especially with scrounged lead. One of my recent favorites is a Lyman for 44-grain 0.224-inch bullets, used for reduced loads duplicating .22 rimfire ballistics in smaller .22 centerfires. A typical lead wheelweight found on the street will produce 15 or so “free” bullets.

Shotshells

So far I haven’t mentioned shotshell handloading, partly because far fewer people load shotshells than they did 30 or 40 years ago. Back then just about every avid shotgunner had a press in their garage, to crank out enough inexpensive ammo for the next weekend’s shotgunning. Today, however, basic shotshells in the two most common gauges, 20 and 12, can usually be purchased for $6 per box. If you shop carefully for components, you can handload 25 1-ounce shells for about $5.50.

Apparently most shotgunners would rather buy a case of factory ammo rather than spend an evening handloading to save 50¢ a box. As a result a lot of today’s shotshell loading is more of a craft than home-factory production. I load some special rounds for every common shotshell—.410, 28, 20, 16, 12 and 10—but for most practice shoot cheap 20- and 12-gauge factory ammo.

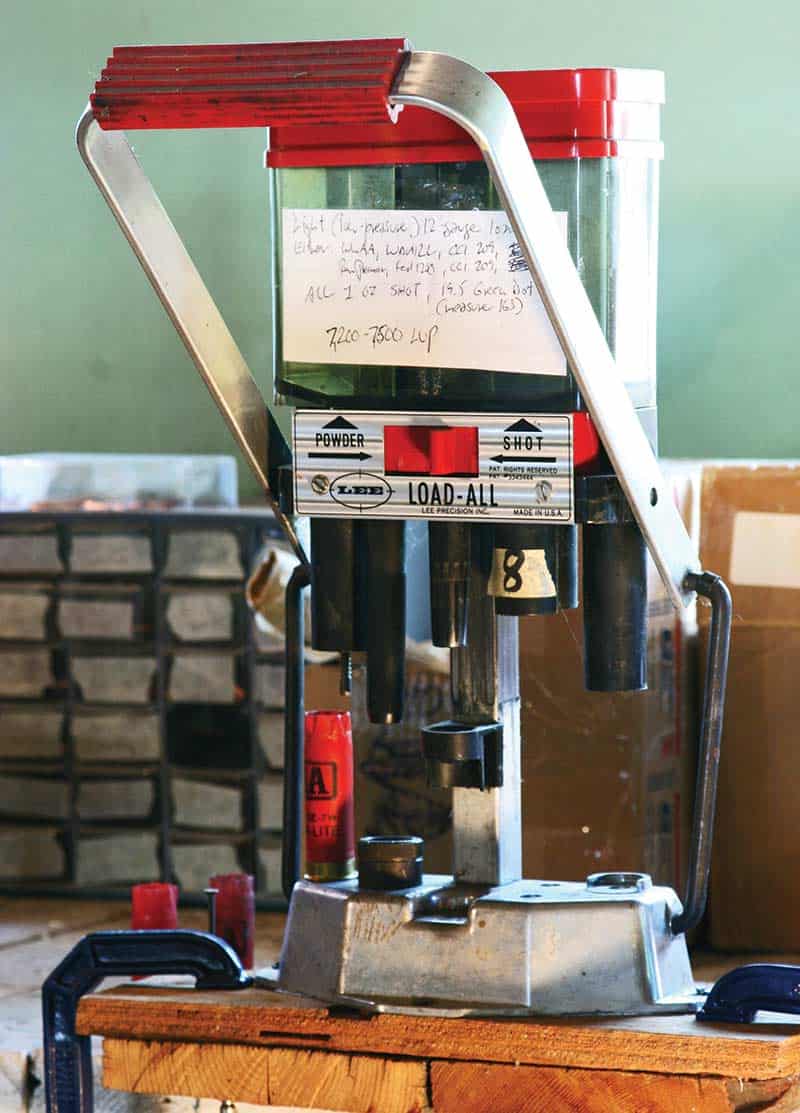

If for some reason you need to produce a lot of shotshells, there are plenty of high-production presses, but also plenty of cheaper alternatives for making a few boxes of specialized loads. Not surprisingly, Lee Precision makes the lowest-priced shotshell press available, the Load-All II. I’ve been using one of the original Load-Alls in 12 gauge since they were introduced in the 1970’s, and have more recent versions in 20 and 16 as well. So far none has had any problems. My original 12-gauge model cost $19.95, and nowadays the price is $75.98, once again beating inflation considerably, since they’re often discounted, but they’re only available in 20-, 16- and 12-gauge models.

Lee also used to make handtool Lee Loaders for shotgun shells, and when in my teens I had a couple in 20- and 12-gauge. The ammo worked fine in break-action guns and most of the time in pumps, but the Lee Loaders didn’t size the brass case heads, and the reloads tended to jam in autoloaders. When the popularity of autos rose, the shotshell Lee Loaders went the way of the passenger pigeon, but I still have a 10-gauge model for my Armas Erbi side-by-side, for producing the relatively few non-toxic loads I shoot at high-flying ducks and geese.

Today’s most affordable shotshell loaders for the .410, 28 and 10 are the MEC single-stage models, available for around $200 or a little less. My .410 and 28-gauge loaders are MEC’s, and they work very well. Since I also have a more than adequate supply of lead shot, purchased a few years ago when the price was half of today’s, they provide a measure of security in an ever-changing world.

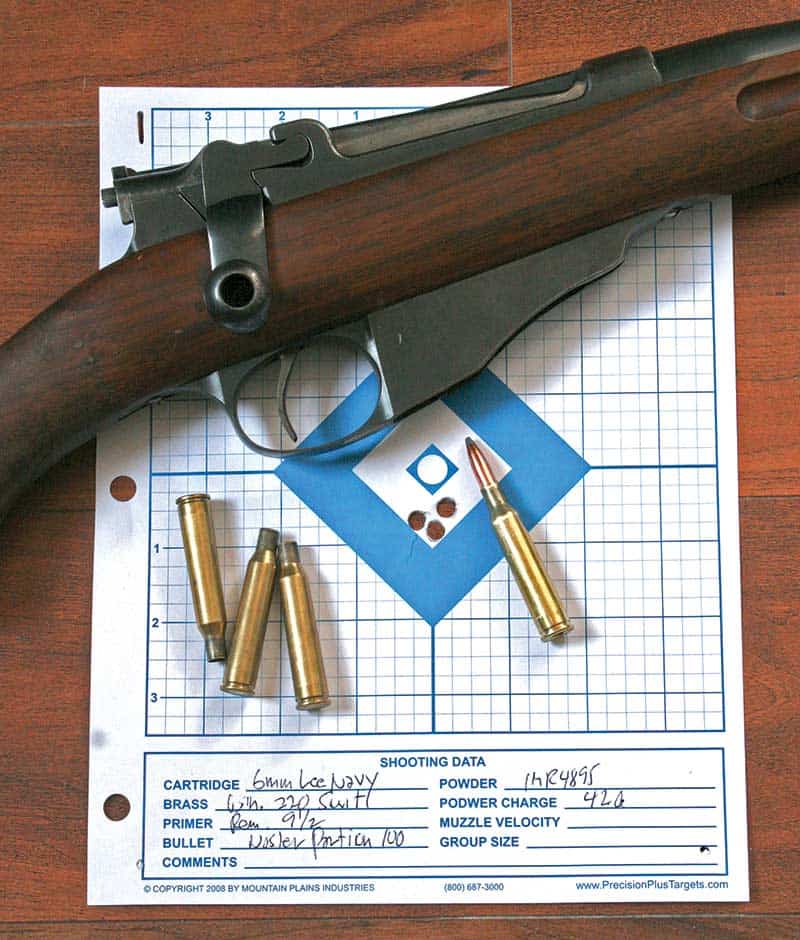

And that’s the most important virtue of handloading. Yes, we can sometimes make better ammunition than the factories, and sometimes save money, but the big deal is independence. Handloaders can even make ammunition no factory produces anymore, providing a sense of satisfaction far beyond saving a few cents or dollars. And that is priceless.

Ballistic Products Inc. (shotshell loading)

P.O. Box 293, Corcoran, MN 55340

(888) 273-5623

https://www.ballisticproducts.com

Brownells, Sinclair Int.

200 South Front Street

Montezuma, Iowa 50171

(800) 741-0015

https://www.brownells.com

Forster Products, Inc.

310 East Lanark Avenue, Lanark, IL 61046

(815) 493-6360

https://www.forsterproducts.com

Hornady Mfg. Co.

3625 Old Potash Hwy.

Grand Island, NE 68802

(800) 338-3220

https://www.hornady.com

Lee Precision

4275 Highway U, Hartford, WI 53027

(262) 673-3075

https://leeprecision.com

Little Crow Gunworks

(WFT trimmer)

6593 113th Ave. NE, Suite C

Spicer, MN 56288

(320) 796-0530

https://www.littlecrowgunworks.com

Lyman Products Corp.

465 Smith Street, Middletown, CT 06457

(800) 225-9626

https://gunsmagazine.com/company/lyman-products-corp

MidwayUSA

5875 West VanHorn Tavern Road

Columbia, MO 65203

(800) 243-3220

https://www.midwayusa.com

Nosler, Inc.

P.O. Box 671 , Bend, OR 97709

(800) 285-3701

https://gunsmagazine.com/company/nosler-inc

Oehler Research, Inc. (chronographs)

P.O. Box 9135, Austin, TX 78766

(800) 531-6900

https://oehler-research.com

RCBS

605 Oro Dam Blvd., Oroville, CA 95965

(800) 533-5000

http://rcbs.com

Redding Reloading Equipment

1089 Starr Road

Cortland, NY 13045

(607) 753-3331

https://www.redding-reloading.com

SmartReloader Products

Helvetica Trading USA, LLC

701 Lawton Rd., Charlotte, NC 28216

(800) 954-2689

http://www.smartreloader.com

Speer

2299 Snake River Avenue, Lewiston, ID 83501

(208) 746-2351

https://www.speer-ammo.com