Double Rifles And Why They Matter

Lethal artwork for lethal animals

Whether it’s the insolent, amber gaze of a lion supremely confident in his lethality, or the wicked hooked horns of a Cape buffalo, the hunters — Capstick, Hemingway, Percival, J.A. Hunter — always seem to be lining up the sights over twin barrels. Sleek, menacing, often gorgeously built and shockingly big-bored, the double rifle is woven through the bloody tapestry of African hunting.

Double-barreled shotguns have been made forever, but double rifles are as different as chalk and cheese. This ain’t your sweet-shooting bird gun full of #8s. There’s no inertia-reset trigger — otherwise, if the first cartridge misfires you’ll die cursing both the slack trigger and the second round it refuses to fire into whatever is trying to eat you. There are seldom exposed hammers — the grasping brush can stealthily cock them, leading to tragedy. They can pose other hazards, as the legendary Frederick Courtenay Selous learned when a double-charged four-bore rifle drove one into his forehead in recoil.

By The Pound

Yes, I said “bore.” Many early doubles were chambered for calibers so large they measured on the shotgun scale of how many lead balls the diameter of the bore it took to add up to a pound. The four-bore fired a four-ounce bullet, while the fearsome two-bore fired a half-pound slug and the relatively-smaller eight-bore threw only 2 oz. of lead per bang!

There are reasons for this. The African explorers who debarked at Mombasa or some other exotic port and wandered inland discovered large, interesting animals who will cheerfully gore, trample, bite or maul you to death with little to no provocation. They’re also devilishly hard to stop. Stopping an attack requires penetration and energy transfer, but since black powder and soft lead bullets were the order of the day, the only way to achieve it was to throw a bigger, heavier ball — with recoil up to and beyond the limits of human endurance.

Twelve-gauge shooters may believe they are inured to recoil but it’s more like a friendly shove from your big uncle who moves houses for a living. High pressure safari cartridges develop a sharper recoil, increasing in intensity with the size and weight of the bullet, delivered through the tiny footprint of the buttpad. Think of it like jousting with 2x4s. They will break teeth; they will break bones.

That kind of impact complicates gunmaking. First is the problem of making a gun that won’t break into pieces, accompanied by a mechanism that can withstand recoil without doubling. Stock design making the gun somewhat easier to manage is also part of the art.

Early African explorers were often English, so naturally British gunmakers created many of these rifles. Repeaters were certainly around — the perfected Mauser bolt action dates to 1898 — but none were large enough to handle the huge blackpowder rounds larger than your average cigar. Thus the development of dangerous game rifles began, and continued, with doubles.

Express Trains

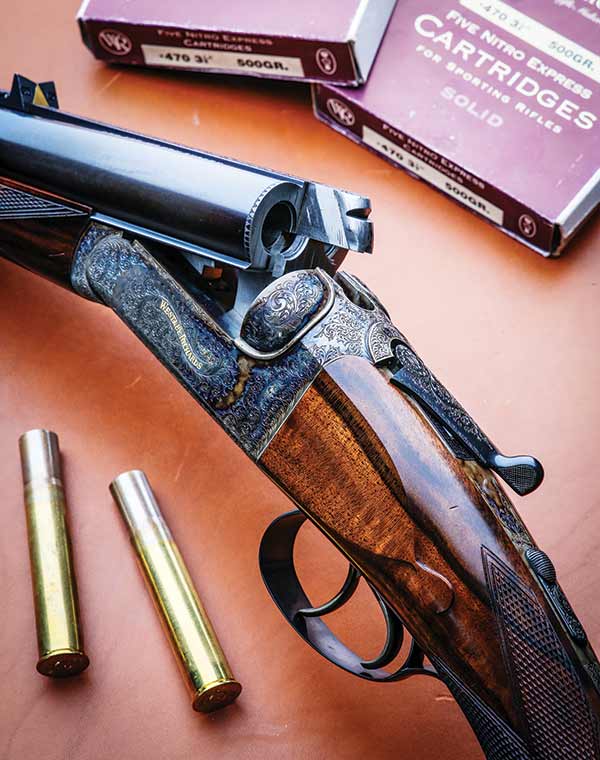

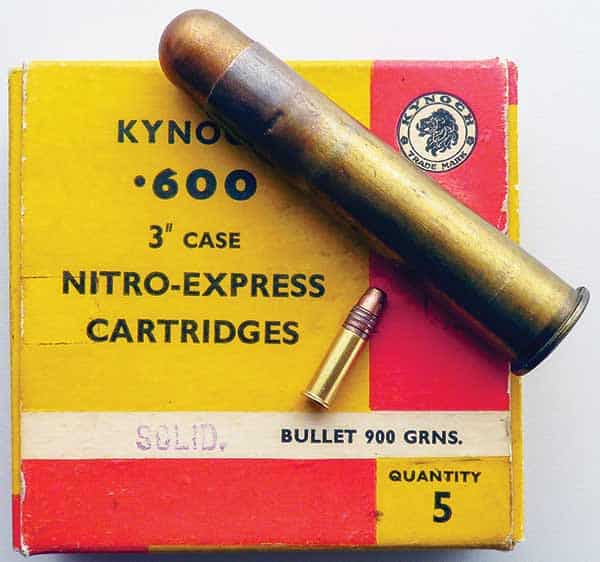

The revolution was not in the mechanism but in the advent of smokeless powder and bullet design. “Nitro” powder quickly supplanted blackpowder, first as “nitro for black” replacement loads for extant calibers, then cartridges designed only for smokeless, most notably the Nitro Express (NE). Nicknamed after express trains by James Purdy, the dozens of high velocity NE calibers ranged from .240 to the quintessentially African .470, .500, .577, .600 and the shocking .700 launching a 1,000-grain bullet at a couple times the speed of sound. The popular .470 Nitro Express remains the definitive chambering for a double.

Advances in power were accompanied by those in bullet design such as the advent of jacketing a soft lead core with a harder metal to create non-expanding “solids,” or a variety of creative hollow- and soft-points. Jacketing made penetration easier to achieve and produced a means to both enhance and control expansion, which generally comes at the expense of penetration.

While nitro cartridges shrank considerably in size from the bulky blackpowder rounds, they were still large and only a single-shot or break barrel could contain them. Putting two barrels side by side added recoil-absorbing weight and an instantaneous second shot, an advantage the double has never lost. It also meant the hunter had, in effect, two rifles — two barrels, two locks, two triggers. If one broke he still had a functioning rifle for the months or years it could take to get it to a gunsmith. Since the over/under arrangement is slower to reload, doubles are almost exclusively side-by-sides which also creates a broad sighting plane allowing them to be shot almost instinctively like a bird gun. Except you’re trying to stop the half-ton buffalo coming for you and if you miss, the winged creatures you see will not be quail.

In keeping with the reality of close-range charges, the sights are designed to be fast. The classic express sight has a round bead front and a shallow-V rear, often with a non-tarnishing gold line down its center for faster alignment. Some also had an auxiliary flip-up “moon” sight of ivory or light-colored metal. The safari rifle is as much a self-defense gun as anything else and the minute-of-lion express sight trades the gilt-edged accuracy of peep sights for the opportunity to live long enough to get back to a target range — a good trade to me. Doubles do not have the tack-driving accuracy of a bolt gun but that’s not what they’re for, and it’s one of the reasons you seldom see one with a scope. Other reasons have to do with speed and weight, which affects the gun’s regulation.

Within Regulation

Putting a sight between two barrels doesn’t guarantee either one will put its bullet where those sights suggest, much less both. Good enough for birdshot isn’t good enough for a rifle bullet. Just as with magnum revolvers, recoil affects point of impact and each barrel recoils away from the other and the bullet strike moves both upward and outward. While some makers currently use a laser to get both barrels lined up, it fails to account for the effects of recoil. This can be so nuanced a double is generally only accurate with the ammunition for which it was originally regulated.

This was even more of a problem in the early nitro days. The blistering African sun can heat up rifle barrels until it’s like cuddling with a branding iron and the heat created additional pressure. When the cartridge fired, the bullet went faster and in a different direction than it did in the cooler temperatures of the sceptered isle on which the rifle was regulated. Thus came “tropical loads,” downloaded to accommodate the added pressure which came from transporting them to a substantially hotter climate.

The traditional way to regulate a double is to solder the barrels together, test fire, separate, adjust and re-solder the barrels. Repeat until it’s right, a skilled, laborious process accounting for much of the expense of a fine double.

Bring Your Checkbook

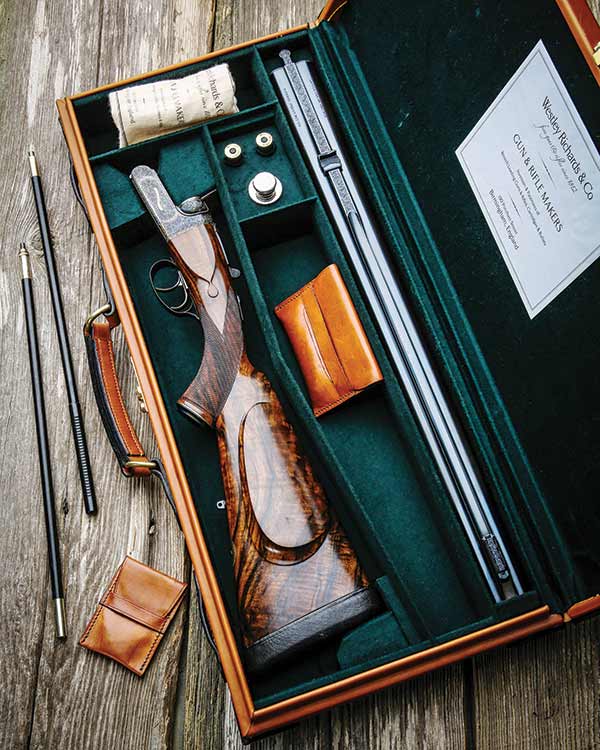

Doubles are expensive, usually starting in the five-figure range and promptly adding a zero when you move into the better-known English maisons such as Purdey, Holland & Holland or Westley Richards. Perhaps because the mechanics of building one make them so expensive, doubles are often finely engraved and built with stunningly beautiful wood since a buyer who can afford $50,000 for a rifle can probably manage the extra expense to make it pretty. It’s ironic to think of hunters caked in dirt, low-crawling through thorns, while clutching a rifle which belongs in an art museum. Chalk it up with the other paradoxes of Africa.

There is one notable exception to the idea a double rifle should cost more than a modest home — the British government contracted with many of the better-known makers to build simple, unadorned working doubles sold in its Army-Navy stores spread across the Empire. Built by makers ranging from Westley Richards to Rigby, Wilkes and others, the unembellished, unmarked rifles offer excellent service but give few clues as to who exactly made them.

Some hints come from the design of the gun. Some makers specialized in box locks, with the firing mechanism built into the frame of the gun, while others used removable sidelocks offering a larger palette for the engraver. Spare sidelocks could also be ordered with the gun, simplifying repair in the field. Westley Richards did one better with the removable frame-mounted drop lock.

Choose Your Poison

Each mechanism has devotees and drawbacks, and each weakens the part of the gun in which it is mounted — box locks remove material from the receiver and sidelocks from the stock.

Another point of contention among aficionados is ejector versus extractor. Many early ivory hunters, who were shooting for volume, preferred the double for its silent second shot — no bolt to run — and disliked the “ping” of ejected cases which they felt was more likely to spook a herd than the disorienting crash of the shot. It was also harder to find the brass to reload. Extractor guns are, however, slower to reload, which gets important when you’re facing animals which, as Elmer Keith noted, occasionally derail passenger trains.

Also, the automatic safety must be pushed off every time the gun is reloaded. Cowboy action shooters deactivate them on coach guns for the same reason dangerous game hunters dislike them. It’s one more thing to get right under stress when facing a trumpeting elephant intent on kneading you into putty.

Of course in a perfect world, no second shot would be needed but things tend to fall apart when you come face to face with your own mortality in an immediate kind of way. For such moments, you want the most efficient tool you can find and the double rifle is track-bred to be the tool.

Much of the added mystique, though, comes from the men who used them, and in upcoming issues we’ll cover doubles used by legendary dangerous game hunters, African and otherwise. Get ready for a wild ride.